As a polytheist, I’ve found that they are many challenges involved with being a woman dedicated to Freyr. One of my biggest issues with Him, and one of the reasons it took me so long to come back to Him, was the myth of how He won his jotun wife, Gerda. It’s a fascinating story told in the form of an old-fashioned narrative ballad (unlike most of the surviving tales), and at first glance it doesn’t really portray Him in a very positive light.

The story, the Skirnismal (from the Poetic Edda), goes like this:

The Introduction

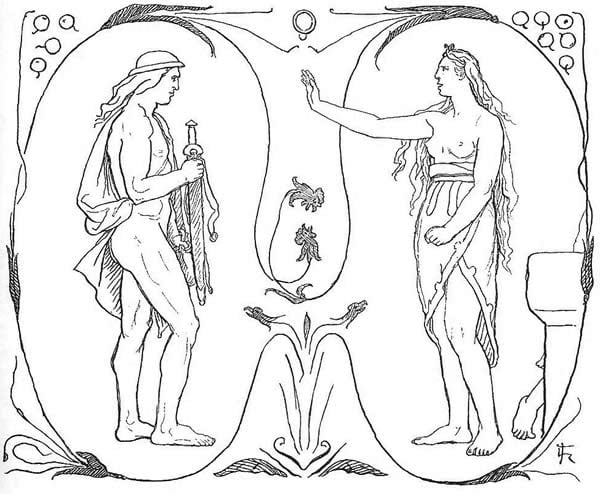

One day, Freyr decides to sit on Hlidskjalf from where he could see all of the things that were happening in all of the Nine Worlds. He sees a beautiful jotun maiden with flashing white arms (“her arms shine, and from them all air and see take light”—Larrington trans.) walking from her father’s home to her garden. He falls violently in love with her, and starts moping.

Njord and Skadi notice that he appears angry, and ask his friend/servant Skirnir to go find out why. He explains that he sat on Odin’s chair and saw Gerd, the female that he loves, but he is upset because he knows that “of all of the gods and all the elves, no one wishes that we should be together”. Skirnir offers to go woo Gerd for him, but only if he gives Skirnir the horse that leaps through fire and the sword that fights by itself. Freyr agrees, and gives Skirnir his horse and sword. Skirnir leaves as soon as it is dark.

Skirnir arrives at Gerd’s home but is met with three barking dogs and a shepherd standing on a mound nearby. He asks the shepherd how he should get in to talk with Gerd. The shepherd says that he’ll never be able to, so why bother trying? Skirnir says that he can’t just sit there sobbing about it—he has to try.

Gerd, for her part, hears the commotion outside and asks her handmaiden to see what’s going on. She describes Skirnir, and Gerd tells her to let Skirnir in so she can offer her visitor some mead. She is worried, however, than he is her brother’s killer (no context is given for this comment, unfortunately).

The Meeting

Skirnir comes in. Gerd asks him what race he is (elf, or Aesir, or Vanir) and why he has come to see her. He doesn’t explain who he is, but he says that he is neither elf nor a member of the Aesir or Vanir, and he starts off attempting to woo forthwith. First he offers her eleven golden apples (or some of Idunn’s apples, depending on the translation) if she will say that Freyr “is not the most loathsome man alive”. She says that her desires will not be bought and that she will never settle down with Freyr.

Skirnir then offers what must ostensibly be Draupnir, Odin’s golden arm-ring that drops eight identical rings every nine nights. She replies that she will not accept it; she has all of the gold she needs here in her father’s hall.

Skirnir then shows her Freyr’s sword, and threatens to cut off her head. Again, she is unswayed, saying “coercion I shall never endure at any man’s desire”, and that her father would kill him if he tried.

The Threats

Finally, Skirnir threatens to use his “taming wand” on her, and lists a long, creative, and detailed set of curses that he will give her. This last part threatens her with everything a woman DOESN’T want: to become a spectacle (or completely ignored); to have her money, independence, and social status taken away; to be so filled with unbearable lust that she will debase her self in front of an ugly giant; and to made to be a beggar at the gate of Hel with only goat’s piss to drink. (I know it’s my heart’s desire to avoid having all of this happen to me, anyway.) He ends his tirade with this curse:

“I write thee a charm and three runes therewith,

Longing and madness and lust;

But what I have writ I may yet unwrite

If I find a need therefor.”(Stanza 37; Bellows translation)

At this, Gerd changes her mind and offers him a glass of the ancient mead, saying that she never thought she would love a Vanir. Before he leaves, Gerd agrees to meet Freyr in nine nights at sheltered a grove of trees that they both know, called Barri.

As soon as he returns, Freyr demands to know the result of his quest. Skirnir tells him that Gerd will meet him in nine days. Freyr, appalled, says that he can barely stand waiting one night without her, much less nine nights.

The End.

About Last Night…

You can probably see how this myth does not portray Freyr in a good light. Here he is, a virile fertility god associated with peace and kingship, who had to resort to some really nasty coercive techniques to get a jotun maiden to marry him. Carolyne Larrington, in her article about the desire and gender dynamics in the Skirnismal, called “What Does Woman Want?” gets to the heart of it: “Few critics have faced squarely the problem offered by a poem which asks its audience to accept and to identify with a hero who coerces a woman into having sex with him.” (4) Granted, it wasn’t Freyr doing the actual coercing, but that doesn’t really absolve Him. No matter how you slice it, it’s coercion.

The Archetypal Analysis

In the archetypal viewpoint, most of these specific details don’t matter. Freyr, as a fertility god and the God of the sun, summer, and “good seasons” represents the coming of Spring. Gerd, associated as she is with frost-giants, protected in her father’s house and unwilling to change her situation represents the cold, hard ground of winter. Skirnir’s “wooing” is really just an increasingly aggressive reminder that Spring will come. Freyr is the inexorable coming of Spring, in every possible way that it can come.

The Polytheist Analysis

The polytheist analysis, however, focuses very specifically on these details. These details can really help us understand more about the Gods we honor. So when I, as a feminist polytheist dedicant of Freyr read the gnarly details of this myth, I run headlong into a rather painful wall of cognitive dissonance. My choices are to either to a) find a way to make it work within my worldview, or b) start looking or a new God to honor.

Filling in the Gaps

When I come to myths like these, I often use a Myth Embodiment exercise to make sense of it all. My previous group, the Vanic Conspiracy, being filled as it was with several feminists who also had initially balked at working with Freyr, did a myth embodiment for the Skirnismal several years ago.

First, as Larrington points out, Gerd’s voice is almost non-existent in the poem. One of the great things a myth embodiment can do is to fill in for those characters who are silent. Let’s try to see this myth from her perspective, shall we?

Gerd is a jotun woman, a Lady of her Hall, who, as far as we know, is living quite contentedly in her father’s lands. She has plenty of money, handmaids to help care for her, and a father who will protect her. As far as we know, all of her wants and needs are being met. Out of the blue, some unidentifiable male comes leaping over her hall’s flaming walls wishing to speak with her (and possibly killing her brother in the process). She offers him the mead, as is customary for a guest, but instead he immediately starts negotiating for her hand in marriage to a leader of an enemy tribe. He insults her by offering her gold (as if she could be bought!) and threatening to behead her. She appears annoyed—but not truly threatened—by this. Seeing that he is losing this battle, he threatens to “tame her” using his taming wand, offending her even further.

(Who wants to be tamed by a taming wand? Seriously. I mean, with prior consent, maybe. But still.)

In the VC’s embodiment, We debated this next section for a while before coming up with one possible solution: Gerd is a jotun. Jotun culture is something like Klingon culture—strength and self-reliance are valued above all things. Jotuns are not terribly bound up by sensitive human-like morals and conscience; they want to know if you can destroy or trick your enemies and protect your land. Gerd, at her father’s house, is completely protected and taken care of (or so she thought). Therefore, anyone who sought her hand in marriage would have to prove that he was at least as much of a bad-ass as her father. She is unaffected by the gold and the sword that fights by itself, but She respects the power of the magic that Skirnir threatens to wield against her. She doesn’t have any protection against that. So, in her mind, Skirnir (and by proxy, Freyr) have proven his strength and might, and therefore his right to take her to Freyr to be his wife.

It’s a mostly convincing argument, but it still leaves me a tad uneasy. Which is where my actual experiences with Freyr come in to play.

My Personal Experience Narrative

Luckily, my actual experiences with Freyr have been of a very loving and comforting deity, not a creepy and coercive one. Unlike His sister, Freya, He is a more introverted being who brings stability, fecundity, and emotional sensitivity along with the His passion. As in this myth, He mopes. He feels longing. In my experience, He is unaware of the power of His presence and is horrified that He sometimes overwhelms His followers accidentally. He is, in many ways, the softer, gentler version of Freya, a description that fits in well with his Viking Age priests, who were also said to be “unmanly” (ergi). Unlike Freya, he descends. Many of us modern worshipers see Him as going “into the Mound” (as do several prosperous kings of old named Frodi). This usually happens sometime after the Fall Equinox. He arises again in the Spring.

This all is not to say that He can’t also be extremely pushy. As in the archetypal analysis, he is the inexorable coming of Spring, as a number of my Freyr-devoted friends have pointed out. He IS the energy that forces crocuses to sprout through the snow and bloom, that makes leeks grow strong and wide and tall in February, and reminds the animals that it’s time to start getting it on. That is his energy, and, like that energy, He can be very overwhelming. However, it is nothing like the creepy coercion that Skirnir threatens Gerd with. In my interactions with Her, few though they’ve been, my sense is that She is fine where She is and that She loves Him very much. In fact, She seems to provide a nice counterbalance for his energy and sensitivity, and She keeps the Hall running while he is away.

Long story short, myths don’t always portray the Gods accurately. However, Knowing Your Lore is a great place to start.

Works cited:

- Larolyne Larrington. “What Does Woman Want?” Mær und munr in Skírnismál*. From A Handbook to Eddic Poetry: Myths and Legends of Early Scandinavia, ed. Larrington, Judy Quinn, and Brittany Schorn. Cambridge University Press: 2016.

- Henry Adams Bellows. The Poetic Edda. 1936.

Patheos Pagan on Facebook.

the Agora on Facebook

Happily Heathen is posted on alternate Fridays here at the Agora. Subscribe by RSS or e-mail!

Please use the links to the right to keep on top of activities here on the Agora as well as across the entire Patheos Pagan channel.