“Light though thou be, thou leapest out of darkness; but I am darkness leaping out of light, leaping out of thee!”

— Moby Dick, Herman Melville

The Summer Solstice occurs on June 21 in the Northern Hemisphere this year. It is the longest day of the year and the shortest night. Summer finally begins here in the Midwest, both meteorologically — with the warming of the air and the increasing occurrence of sunny days — and socially — with the end of the school year. (Which is why I don’t call the day “Midsummer” — “Midsummer”, for me, falls after Lughnasadh in early August.) The summer solstice is the twin to the winter solstice which falls around December 21. The day is called “Litha” by many Pagans. “Litha” is the name given to the summer inter-calendary period by the Anglo-Saxons, just as “Yule” is the name they gave to the winter inter-calendary period — which is where we get the name Yule for the Christmas-tide.

I’ve got a somewhat different take on the Summer Solstice than many other Pagans. Many Pagans celebrate the summer solstice by honoring the light. That’s natural enough. It’s summer after all. What’s more natural than to celebrate the light in the summer? Often summer solstice rituals are performed at high noon (much to the chagrin of those standing under the sweltering sun in ceremonial robes) — just as some winter solstice rituals are performed at midnight. But for me, the summer solstice is as much, if not more, about the darkness than the light. The summer solstice is the longest day, but it is also the day when the days begin to grow shorter again and we anticipate the decline of the year. It has always seemed odd to me that we Pagans should celebrate the light at the winter solstice and again at the summer solstice.

Neo-Paganism, as I understand it, is all about balance. It is about bringing opposites together into harmony. At the winter solstice, we celebrated the birth of the Sun Child from his mother, the Goddess, Mother Night. (This Neo-Pagan myth is mirrored somewhat in the Christian Nativity.) And if we celebrated the birth of the Sun Child on the longest night, what else would be celebrate on the longest day but the birth of the Dark Child from his mother, the Goddess of the Sun?

The myth of the birth of the Dark Child is a wholly new myth, invented for Neo-Pagans. In some ancient pagan traditions, the Sun is a male God, but in others she is a Goddess. For example, the ancient Japanese worshiped a goddess of the Sun called Amaterasu. And the Egyptians worshipped a sun goddess, Sekhmet, who had the head of a lion. But in neither of these cases did the Goddess have a son — at least not that I am aware of. In spite of its absence of (paleo)-pagan antecedents, I think the myth of the Dark Child fits perfectly with the Neo-Pagan mythos and the Wheel of the Year.

The Dark Child is born at Litha and will eventually grow up to be what Neo-Pagans call the Holly King, the King of Winter. He will battle the Oak King, the King of Summer, who was born on the opposite point on the Wheel of the Year, at Yule. In the Neo-Pagan myth the Sun Child and the Dark Child are twin brothers — not identical twins, but mirror twins. The story I tell my children is that the Dark Child was born out of the shadows that are cast by the summer solstice fires (“darkness leaping out of light”) — fires which both represent the consummation of the love of the Goddess and her Consort and presage the impending immolation of the Consort in August.

This Neo-Pagan myth is reflected in the Celtic myth of two kings, Gwyn and Gwythr, the white son of the night and the dark son of the day who battle for the love of a maiden, representing the Neo-Pagan Goddess. The myth of the Dark Child is also reflected in the Egyptian myths about Set, who burst from his mother’s side prematurely, grew to be his brother’s slayer, and is ultimately slain in turn by his brother’s son. It is reflected in the Norse myths about Loki, who orchestrates the death of the Norse sun god, Balder, and sets into motion Ragnarok, the doom of the gods. And it is reflected in the Arthurian legends about Mordred, Arthur’s illegitimate son who takes his fathers throne (and his wife) while Arthur is away, after which the two slay each other.

The Dark Child represents, for me, the seed of destruction at the heart of all endeavor — in Hegelian terms, the antithesis to every thesis, which leads eventually to a new synthesis. He is present in all our deeds, all our thoughts, all our desires, all our dreams. But the Dark Child is not evil or bad. Just as the light half is not good, per se. They are both part of a whole, and it is the the whole that is good.

The Christian myth contains these anti-theses in form of Christ and Satan (or the Anti-Christ). Carl Jung theorized that the Christ figure represents the self, while the Satan or the Anti-Christ represents the Shadow — that part of ourselves that we repress and refuse to recognize:

“If we see the traditional figure of Christ as a parallel to the psychic manifestation of the self, then the Antichrist would correspond to the shadow of the self, namely the dark half of the human totality, which ought not to be judged too optimistically. So far as we can judge from experience, light and shadow are so evenly distributed in man’s nature that his psychic totality appears, to say the least of it, in a somewhat murky light. … In the empirical self, light and shadow form a paradoxical unity. In the Christian concept, on the other hand, the archetype is hopelessly split into two irreconcilable halves, leading ultimately to a metaphysical dualism—the final separation of the kingdom of heaven from the fiery world of the damned.”

Jung explains that, prior to the Manichaean influence upon Christianity, Clement taught that God ruled the world with his right and his left hand, the right being his son Christ and the left being his other son Satan — the two providing a kind of balance in the “paradoxical unity” that is God. Later, however, Christianity became dualistic, splitting off one half of these complementary opposites, personified in the irreconcilable figure of Satan (and thereby creating the “awkward” problem of theodicy). According to Jung, Satan is a necessary psychological response to the pathologically one-sided nature of Christ:

“Psychologically the case is clear, since the dogmatic figure of Christ is so sublime and spotless that everything else turns dark beside it. It is, in fact, so one-sidedly perfect that it demands a psychic complement to restore the balance. This inevitable opposition led very early to the doctrine of the two sons of God, of whom the elder was called Satanael. The coming of the Antichrist is not just a prophetic prediction— it is an inexorable psychological law … every intensified differentiation of the Christ-image brings about a corresponding accentuation of its unconscious complement, thereby increasing the tension between above and below.”

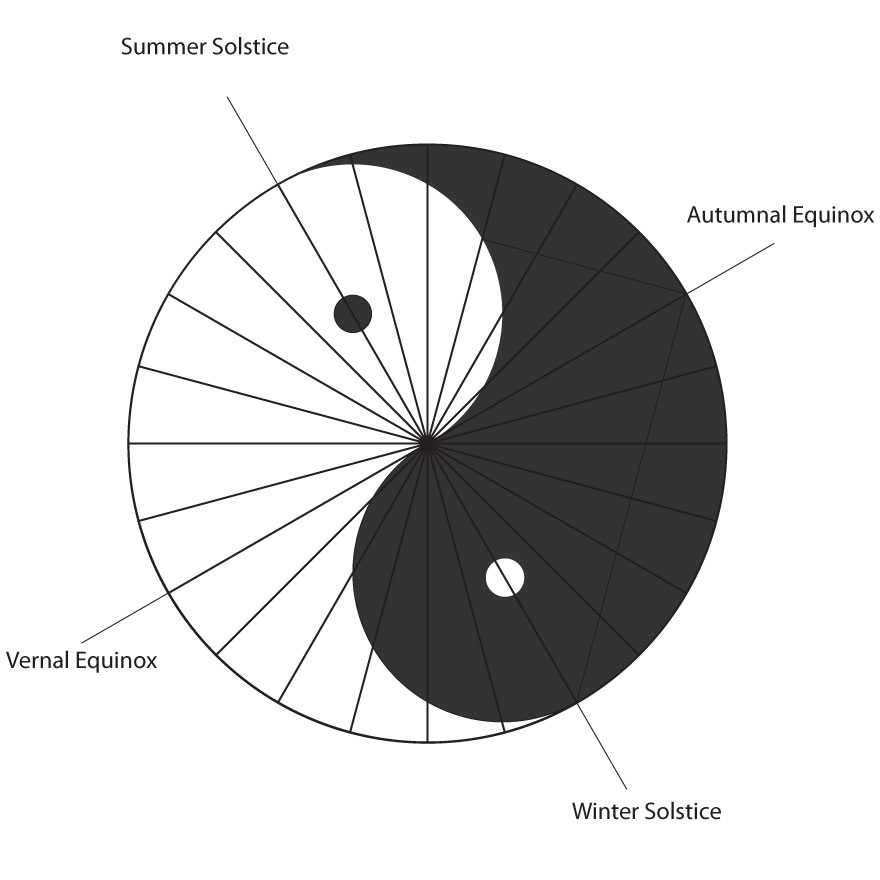

In Neo-Paganism, these previously irreconcilable images are brought together again and reconciled in the gestalt of the Wheel of the Year, in which these two archetypes are held in a dynamic and creative tension. We might visualize the relationship of the Sun Child and the Dark Child as the Chinese symbol of the yin-yang. To a Neo-Pagan, the light spot on the dark field may represent the Sun Child born from the womb of the Goddess of Night at the winter solstice. And the dark spot in the light field may represent the Child of Darkness born from the Goddess of Day at the summer solstice. The two are balance and unified in the movement of the Wheel.

For me, then, the summer solstice is not about the light, but reclaiming the dark. In the words of Starhawk:

“… we begin by making new metaphors. Without negating the lght, we reclaim the dark: the fertile earth where the hidden seed lies unfolding, the unseen power that rises within us, the dark of sacred human flesh, the depths of the ocean, the night — when our senses quicken; we reclaim all the lost parts of ourselves we have shoved down into the dark. Instead of enlightenment, we begin to speak of deepening …”

— Starhawk, Dreaming the Dark