The public comment period for the Draft Pagan Community Statement on the Environment began this week (and will end April 21). One of the points under discussion is the use of a preposition.

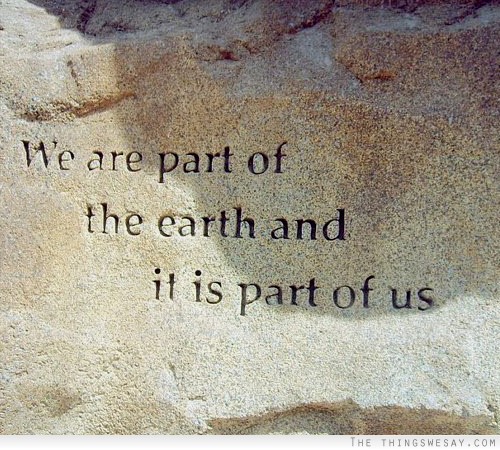

The sentence in question is: “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.”

The proposed change is: “We are of the Earth, and the Earth is part of us.”

For context, here’s the section of the Statement which the sentence can be found in.

We are part of the web of life

In recent decades, since the revival of what has been termed “Neo-Paganism” and the “Back to the Land” movement of the 1960s, many contemporary Pagan religious traditions have stressed humanity’s interconnectivity with the rest of the natural world. The ancient realizations of many of our ancestors, that the Earth is itself a living organism and that all life on Earth is interconnected, have been supported now by the scientific method and our expanding knowledge of the universe.

The very atoms we are made of connect us to the entire universe. Our hydrogen was produced in the Big Bang, and the other atoms essential for life were forged in the scorching furnaces of ancient stars. Beyond atoms, the molecules of life connect us to Earth, showing that we don’t live “on Earth” like some alien visitor, but rather that we are Earth, just as a volcano or river is part of Earth and her cycles.

We are earth, with carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus making up our bodies one day, and incorporated into mountains the next. We are air, giving food to the trees and grasses when we exhale, and breathing in their gift of free oxygen with each breath. We are fire, burning the energy of the Sun, captured and given to us by plants. We are water, with the oceans flowing in our veins and the same water that nourished the dinosaurs within our cells.

We are connected to our families, through links of love, to their relatives, and so on to the entire human species. Our family tree goes back further than the rise of humans, including all mammals, all animals, and all life on Earth. The entire Earth is our immense and joyous family reunion.

We feel these connections in a spiritual way. The web of life includes strands that tug on our hearts, thread through our essential nature, and weave us into a spiritual whole. As part of the body of life on Earth, we care about the health of all parts of the body. Many human activities destroy parts of the body, and we recoil at them. Cutting down a rainforest is no different than cutting off a healthy leg or arm. In fact, these are even more vital than our arms and legs, because these forests are part of our planetary lungs. Similarly, we care about our waters, our land, our air, and our diverse biosphere. We do so out of respect for our ancestors, out of care for all life today, and out of love for future generations. Anything that harms the body of life on Earth, including global warming, pollution and extinction, is thus a spiritual and moral issue.

We are the Earth, the Earth is us.

There’s several issues here.

One complaint is that the existing language is not accurate. We might say that, “Leaves are a Tree, a Tree is Leaves,” which might be true in one sense, but not in another. John Seed has expressed a common sentiment among deep ecologists: rather than saying “I am defending the rainforest,” we should say, “I am the forest, recently emerged into consciousness, defending myself.” But some have expressed concern that the existing language, “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.”, might be taken over-literally and misunderstood. Others feel it is a completely accurate statement that is literally true. While still others feel that the statement is a poetic “shorthand” which serves to remind us humans of our interconnectedness with the Earth. Unlike leaves in relation to a tree, human beings have a unique ability, even tendency, to forget that connection. The existing language arguably derives its power from its over-generalization. Something may be lost by adding the prepositions, in fact, that very quality which engages the emotions and moves us to change our behavior. Set off as it is and position near the middle of the Statement, the sentence “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.” acts structurally as a kind of keystone for the entire Statement, encapsulating the thesis in a concise and powerful expression.

Underlying this discussion is a difference of opinion over role of metaphor. For some, metaphor is merely a clever literary construct, a rhetorical flourish, one that is confusing and potentially misleading. For others, metaphor — including metaphorical language like poetry and metaphorical action like ritual — isn’t just a pretty way of saying something that could be said more directly. Rather, metaphor points to something that cannot be fully expressed in representational language. Or rather, instead of pointing to something, it invites us to experience something, something which transcends language. The sentence, “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.” may be better inviting such an experience.

Underlying this discussion is a difference of opinion over role of metaphor. For some, metaphor is merely a clever literary construct, a rhetorical flourish, one that is confusing and potentially misleading. For others, metaphor — including metaphorical language like poetry and metaphorical action like ritual — isn’t just a pretty way of saying something that could be said more directly. Rather, metaphor points to something that cannot be fully expressed in representational language. Or rather, instead of pointing to something, it invites us to experience something, something which transcends language. The sentence, “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.” may be better inviting such an experience.

At the risk of making an unfavorable comparison, this discussion reminds me a little of the centuries-long debate about the use of a certain pronoun in the Nicene Creed. The pronoun — actually the clause including the pronoun — has its own name: the “Filioque” [Latin: (from) the son]. Here it is in context: “And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and (from) the Son.“ Apparently, whether the phrase is included and how it is translated has important implications for understanding the doctrine of the Trinity. From what I understand, the phrase itself has become symbolic of conflict between the Eastern (Greek) Orthodox and Western (Latin) Catholic churches.

In the same way, the debate about the absence of pronouns in the sentence, “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.”, may be symbolic of the divide in the Pagan community between those who employ theistic language (either literally or metaphorically) and those who do not. Perhaps there are also theological assumptions involved as well. On the one hand, adding the clause “part of” implies that there is part of us that is not terrestrial, while its omission does not. The phrase may privilege a pantheistic perspective which is not shared by many Pagans. But one can be a polytheist and believe the gods are separate from us, while also believing that “we (the gods and us) are the Earth” — something that I’ve heard many times from polytheists.

In any case, the purpose of the Pagan Community Statement on the Environment is not to create some kind of Pagan Creed, but to make a statement about what being Pagan means for our relationship to the Earth and to offer our unique perspective on the causes of the environmental disaster we are facing. It is a political statement as much as a religious statement. Which phrasing better accomplishes that purpose?

What do you think? Which is better? “We are the Earth, the Earth is us.” OR “We are of the Earth, and the Earth is part of us.”?