Too Close for Comfort

In my last post, I wrote about the discomfort that we feel when it seems that others are appropriating our most sacred symbols. There is a kind of cognitive dissonance we feel when we encounter some other peoples’ Paganism that is at once different, and yet too close for comfort. It’s ironic that we can sometimes be more disturbed by the beliefs and practices other Pagans or Polytheists than we are by Christians or other religions that are less similar to our own. Why is that? I think there’s something about the juxtaposition of the similarity and the difference that is particularly threatening.

In undergraduate school, I majored anthropology and I studied the phenomenon of cultural boundary maintenance in a small Mormon community which had been divided by the emergence of a heterodox Mormon group. The heterodox group, which had begun as a private study group of orthodox Mormons, eventually came to represent a threat to the orthodox Mormon identity because the group was different, and yet all too similar to their orthodox Mormon neighbors.

As a result, I expected to find that the orthodox Mormon community working overtime to establish a new cultural boundary separating itself from the heterodox or “apostates” group. Of course, there were institutional mechanisms for this — the heterodox group was eventually excommunicated — but I was interested in how this was done extra-institutionally. What did people say about the heterodox group? What stories did they repeat? How did they mock the apostates? What was said in public and what was said in whispers? How did they reconstruct their cultural identity?

But I never really found what I was looking for. Part of the reason, I think, was because I was looking in the wrong place. I was looking on the boundaries, what some Mormons have come to call the “borderlands.” I was talking to people who were sympathetic to the apostate group, but yet remained orthodox, and to those ecclesiastical authorities charged with enforcing the boundary. I hoped they would help me find the new cultural boundary which had been drawn. But maybe I should have been looking in the center, in the heart of the Mormon community. Maybe I should have been looking, not for a new boundary, but for a reconsolidated center.

Defining Community from the Center

It seems to me there are two ways of defining community: at the edges and from the center.

The problem with defining community “at the edges” is that we end up trying to draw bright lines where there is a fuzzy overlap, and without the institutional mechanisms to enforce such divisions, the effort is largely wasted. As John Beckett has observed, as much as we’d like to draw bright lines, “religious boundaries are more like beaches, the boundaries between the Land and the Sea – they’re indeterminate and they shift all the time.”

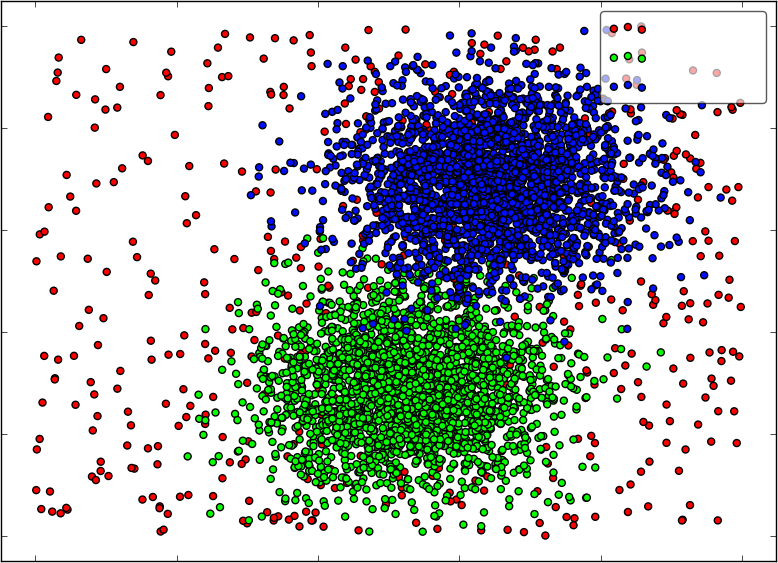

Consider the scatterplot graph to the right, which might represent the Neo-Pagan and Polytheist communities (although I suspect that our communities are even more enmeshed than this graph). Is there a difference between the green and the blue? Yes, but where exactly is the diving line? We would have to do some serious gerrymandering to draw that line. Not to mention, who is going to enforce the line?

I think it makes more sense to define our communities “from the center” — or better yet, from multiple overlapping centers (after all, neither grouping is a perfect circle). This is what we do when we make lists to describe Paganism or Polytheism. For example, I have listed (1) nature, (2) polytheism, and (3) magic as central to Neo-Paganism. Isaac Bonewits listed (1) polytheism, (2) immanence, (3) environmentalism, and (4) magic/ritual. And here are some other lists.

Inevitably, people get upset and say that one or more of the items on the list does not describe them, or they say that something essential was left off the list. But they are looking at community “at the edges”, rather than from the center(s). These lists are not intended define where Paganism or Polytheism end, but where they begin. They describe the multiple centers around which we congregate, not the boundaries which separate us from others.

The challenge of defining community “from the center” is that you have to tolerate a fair amount of ambiguity the closer you come to the edge of your community … and this is difficult, especially when a community is in its formative stage.

The Adolescence of the Polytheist Movement

Lately, we’ve seen a lot of writing from those in the Polytheist movement*, including one or two at Patheos, about their community and the intersection with Neo-Paganism. A lot of this writing seems unnecessarily divisive from the perspective of those closer to the Neo-Pagan center(s). I would suggest that the reason for this is that the Neo-Pagan and Polytheist communities are at different stages of cultural development. And defining identity “at the edges” may be a characteristic of an early stage of the development of a religious community, just as, on an individual level, adolescents tend to define themselves in contrast to their inherited cultural identity.

Although Neo-Paganism was influenced by post-war British Traditional Wicca and had its roots the Romantic Movement, following Sarah Pike, I date Neo-Paganism to 1967, which was the year that three significant Neo-Pagan groups were organized: Feraferia, the Church of All Worlds, and the New Reformed Order of the Golden Dawn (NROOGD). That means that Neo-Paganism will be 50 years old next year! Which means that we are now working on our third generation. That’s not a really long time in the history of religions, but it’s not insignificant either.

In contrast, the contemporary Polytheist movement*, although it has its historical antecedents and ancient roots, is probably only about 15 years old — not even a generation yet. And this makes a difference for how we construct our respective identities.

The contemporary Polytheist movement is still in its formative years. In Neo-Paganism’s formative years, it was common for Neo-Pagans to define themselves “at the edges”, specifically in contrast to the Abrahamic religions. Many still do — especially when we first come to Paganism — but it seems increasingly common for us to collectively define Neo-Paganism “from the center” and content ourselves with some degree of fuzziness at the edges.

(Incidentally, it was common for Neo-Pagans, 40 years ago, to make unsupportable claims about the alleged antiquity of their faith, claims which have now been largely abandoned, just as some in the Polytheist community today balk at the suggestion that their religion has relatively recent origins.)

In some ways, the Polytheist movement is a recent outgrowth of, and a reaction to, contemporary Paganism. From this perspective, Neo-Pagans can look at what is going on in the Polytheist community as a normal stage in the development of a new religious community. I know it’s hard to watch — especially when we Neo-Pagans are made into strawmen by some in the Polytheist movement, like parents being vilified by their teenage children. In psychology, this process is called “individuation” or “differentiation.” And we should expect that some in the Polytheist movement will be highly reactive at precisely the points where Paganism and Polytheism overlap, for the same reason that adolescents tend to be most reactive to those closest to them.

This may sound condescending, but the contemporary Polytheist movement is in its adolescence, and like every adolescence, it’s awkward and accompanied by a lot of exclamatory rhetoric … but it will be outgrown.

Of course, just as there are adolescents who are wise beyond their years and more mature than their parents, there are also parts of the Polytheist movement which are like this. I suspect they are made up of people who are more concerned with cultivating a rich cultural center than with building walls at the boundaries.

So for those of us in the Neo-Pagan community, let’s have patience with our younger sister faith. And let’s not forget that older religions can still learn something from newer ones about vitality and enthusiasm. And for those in the Polytheist community who dwell on the edge, perhaps they might consider turning their gaze to the center and letting the borderlands take care of themselves.

* Note: As used above, the “Polytheist community” and the “contemporary Polytheist movement” are distinguishable from polytheistic Pagans and polytheists in the (Neo-)Pagan community. A person may be a polytheist or polytheistic without being a part of the “contemporary Polytheist movement”. As P. Sufenus Lupus Virius has explained: “Everyone who is a Polytheist is also polytheist, but not all who are polytheist are Polytheists.”