By Madiha Waris Qureshi

Some analysts insist ISIS is a natural and unavoidable product of Islam. They couldn’t be more off-base.

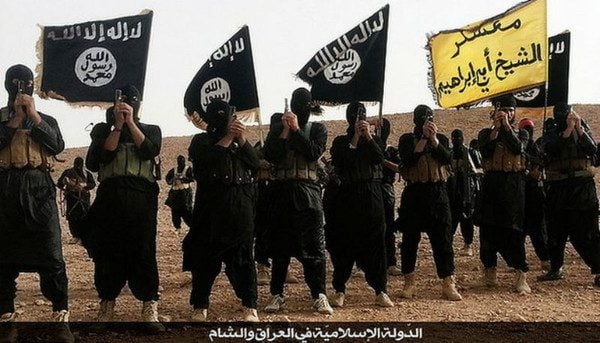

Since the alarming rise of the Islamic State, many political analysts and pundits across the world, especially in the West, have taken it upon themselves to inform more than 1.5 billion Muslims of the world that most of them – millions of them – are wrong about Islam.

These analysts argue that ISIS is the only entity that’s truly honest about Islam. It is free of the hypocrisy of candy-coating moderate Muslims or of the Western leaders eager to forge alliances with them, and that when both denounce ISIS as un-Islamic, they’re not just being silly, but also dishonest.

By casting a majority of Muslims and their leaders into the role of apologists for Islam, New Atheists like Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins, as well as former Muslims like Ayaan Hirsi Ali make the case that it’s impossible to defeat ISIS without recognizing the true barbarity contained within certain Islamic verses. The real enemy then is not one group’s sociopathic interpretation of these verses, but the verses themselves.

So astutely made are these arguments that they succeed in sowing seeds of further mistrust and horror at Islam’s (and the Quran’s) apparent penchant for atrocities into the mind of the average non-Muslim who is regularly bombarded with violent images of Muslims across the world.

However, this narrative of “true Islam” as being literalistic alienates millions of Muslims across the world, who are just as appalled by ISIS’ viciousness as their non-Muslim counterparts. Telling Muslims that their denunciations are not actually reflective of their own religion is not just condescending; it’s also similar to the logic used by hardline and radical extremists themselves, namely:

A) You’re not Muslim if you don’t take every religious text literally; and

B) You’re not Muslim if you challenge a traditionally accepted literal interpretation.

Is it Un-Islamic to Question Tradition?

Journalist Graeme Wood in his recent analysis for The Atlantic wrote, “Muslims can say that slavery is not legitimate now, and that crucifixion is wrong at this historical juncture. Many say precisely this. But they cannot condemn slavery or crucifixion outright without contradicting the Koran and the example of the Prophet.”

Actually, no, Muslims can condemn slavery, crucifixion and many other evils that ISIS claims to be Islamic without contradicting Islam. They can do this by studying the context of the times when verses mentioning slavery (et al) were recorded, and then comparing it to the vastly different world they live in now. They are also full within their Islamic bounds to apply that oft-ignored tenet of Islam that the Prophet himself advised Muslim scholars to use: Ijtehad (independent reasoning), because he, unlike ISIS, believed the world would change, and his teachings could not possibly have all the correct answers for every worldly challenge that would arise after him.

Ijtehad didn’t just materialize out of the blue. It is an Islamic legal term and a principle of the Islamic jurisprudence. It was prescribed to help Muslim theologians and scholars make educated decisions where Quranic verses and the Prophet’s sayings (Ahadith) lacked guidance for complex issues, and to essentially keep Muslim interpretation of Islamic texts up-to-date with the changing times.

To ignore the existence of Ijtehad in Islam is to deny the significant opening for re-interpretation that Prophet Muhammad himself created for Muslim scholars. And this denial is the hallmark of the literalistic ISIS school of thought as well as of those who claim Islam as being hopelessly incompatible with the modern world.

The Importance of Nuance and Context

Understanding the context and time in which Quranic verses and Ahadith on a host of controversial social issues were recorded, ranging from slavery to polygamy, is important for Muslims as well as those who think denouncing ISIS and Islam are the same thing. Here’s why:

More than 1,400 years ago, slavery was a fact of life (just as it was in the American South less than two centuries ago). More than 1,400 years ago, polygamy, savage treatment of women and slaves, incest and many other social ills were also widely accepted traditions. Prophet Muhammad tackled many of those ills in his quest for reform in various ways that were politically sound and strategically far-reaching. He limited the widespread practice of unlimited polygamy to four and laid down strict rules for equal treatment of wives, which was unheard of.

He banned a brutal tradition of burying daughters alive; denounced a norm where men would forcibly marry their fathers’ wives after their death; and included women in inheritance laws for the first time. They were not given equal inheritance rights; but that they received billing in inheritance at all was a revolutionary idea for that time. He also created rules for humane treatment of slaves and freed several of his own, one of whom went on to become a respected scholar – again, an unprecedented occurring.

All these and more acts were groundbreaking reforms for a pre-Islamic Arabian society (Jahiliyyah) that had no civil rights recognition at all. For their time, these reforms were revolutionary. Are they revolutionary for our time? No. And that is exactly why it is reasonable, not hypocritical or un-Islamic, for Muslim scholars to build upon many of those teachings using Ijtehad, in accordance with what they know now.

From advancements in criminal investigative abilities to the vastly different access to education and information available to women and men alike, the justifications and uses for Ijtehad are endless. The only constant that needs to be upheld is the spirit of social reform and humanitarianism reflected in Prophet Mohammad’s approach, set against the backdrop of an astonishingly chaotic society. For its time, Islam was the most modernistic and progressive ideology to hit Arabia. That progressive spirit is the constant Muslim scholars need to embrace.

As Dr. M. A. Muqtedar Khan, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at University of Delaware writes in his essay on the subject, “A broad vision of Ijtehad ensures that Islam and Muslim communities continue to reform in positive ways without losing the connection to Divine revelation and traditional culture. Muslims must continue to embrace this spirit of inquiry and desire for all forms of knowledge in order to revitalize and restore Islamic civilization.”

In the U.S., Americans accept that their Founding Father Thomas Jefferson could have slaves and still be a revolutionary leader of free thought and expression. They do this because Jefferson was borne out of a time when slavery was a fact of life, and they understand the context in which he operated. They can still accept him as a great man despite his not denouncing one of the most brutal traditions of his time.

Is it so out of ordinary then to give that understanding of context and time to a leader who was borne out of a society so medieval, it buried its daughters alive? Once we have conceded this historical fact, we must also accept that literalistic interpretations of Islamic texts belong to the medieval era they were recorded in. Islam opened the door to modernity to those living in that era; it is time its current guardians start doing the same now.

The version of Islam followed by ISIS does not belong in this world and time, and all of Muslim world is not ISIS. The fight against ISIS is dead on arrival if we don’t forgo that assumption.

Madiha Waris Qureshi is an international development professional and a freelance writer. She is based in Washington, D.C. Madiha tweets at @MadihaQ.