This is Day 29 of Altmuslim’s #30Days30Writers series for Ramadan 2015.

By Precious Rasheeda Muhammad

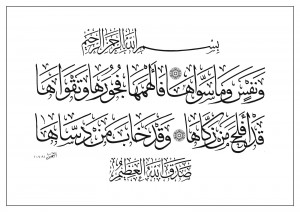

“There is no soul but has a protector over it.” —The Holy Quran, Surat At-Tariq, 86:4

We were in our navy blue Dodge Caravan, the one my husband Carl travelled from Virginia to New Jersey to buy from a government auction, the one that reads “Secaucus Board of Education” when pollen season hits, because, hard as we try, we just can’t seem to remove the last of the sticker residue left by the previous owners; so we are constantly outed by the fine yellow film from the pine trees, layering — like a fingerprint dusting — over what remains of the letter shapes.

Carl was driving, and, occasionally, when he rolled up too fast on a red light, he instinctively reached out his arm in front of my chest, shielding me back in my seat, to keep me from propelling forward, even though I already had on a seat belt. I’ve grown to expect this when he drives, and to miss it when it doesn’t happen, even when we are heartbreakingly upset with one another.

Once I tried it on him, reaching my girlish arm from the passenger side, across his broad chest, just at that moment when the car jerked forward and jerked back. I did it just to see what he would say. His response was a boyish laugh that I hadn’t heard in a long while, that sound of carefree release I had first experienced from him when he foolishly slid down the steep subway banister in Cambridge’s Kendall Square and jumped off — all 6 feet 3 inches tall, 200-plus pounds of him — before hitting the bottom step. Silly boy, I’d thought to myself. He was a graduate student at Harvard back then, just 22-years-old, and I was already too serious at 28.

We were on our way home from running errands, that day in the Dodge. Our daughters — Mirembe, 8, and Nyota, 6 — were in the back seats chattering away, and I was staring out the window, quietly agitated. Yet another day will pass without the long drive I have been requesting, I know it, I said to myself, matter-of-factly.

Let’s go for a ride, please, I had been pleading for a few weeks now — a ride with no direction, a ride just to enjoy the wind whispering through the window, the warm Virginia breeze massaging its way across our faces. A calming ride, a labyrinthine one with a visually pleasant country road feel.

Carl had constantly promised he would do it another day, a day that had yet to come. We can’t just waste gas, he’d told me over and over again. Of course I understood, but wasn’t he also the one who always said we had to live life, too? That we weren’t in college anymore? Of course not being in college anymore was his broad stroke way of saying we are not in any type of school situation where we have to live the Spartan life. He had three jobs while he was in graduate school, and was still broke. He reminds me of this often.

I hadn’t asked him about the long ride on this drive. But my body language said it all, my last nerve was ticked and I sat, body turned awkwardly away from him, glaring out the window, waiting, unconsciously, for the usual on-the-way-home landmarks to fly by as we passed on our route.

I didn’t see them though.

Something was different.

In my frustration, I had lost track of where we were.

Where are we?

My body relaxed a little as I started to look around to get my bearings.

Are we lost?

No, we could never be lost. My husband plans cities and roads for a living. He always knows where we are going. He always has a plan.

This day, he drove and drove and drove. The more he drove, the more I played a game with myself. He will stop here and the ride will be over. No, he will stop here and the ride will be over.

It was my defense mechanism, so that I wouldn’t get too excited about the possibility of what this was, and then be disappointed when I realized what it was not.

Okay, we will turn back here.

But we glided on, no stopping, no turning back.

The late afternoon nonchalantly turned into evening, the sky almost touching the ground with its brilliant reds, blues, burnt oranges and yellows.

At least that is the way it appeared.

I felt like a kid again, riding with my daddy in Mobile, in Boston, in Chicago, in Gary, with my sister and brothers, with my mother, except I was with a new family of my own now, sharing this favorite thing of mine with my husband and my children.

I became very calm. I couldn’t remember my frustration. A playground whipped by, a lake with a waterfall, luscious green trees, branches reaching out far and dipping low. Street names were turning into route this and route that, roads were narrowing from four lanes to two — were we even still in the same city? — the chatter of the children had stopped, they had fallen asleep.

I was feeling lulled too, by the cool breeze, by the warm calm, by the fresh air. But I fought the urge to doze.

I didn’t dare miss this ride.

I had long stopped keeping track of whether this location or that location would be the end. The end of this … joy ride. I peeked over at Carl. He wasn’t saying anything. He was just driving and driving. I was just riding and riding.

It was so quiet and peaceful.

Here is the ride you have been pleading for, he never once said that. I didn’t say anything either, not even thank you. I didn’t reach out to hold his hand, though I wanted to. I didn’t caress his clean-shaven, dark chocolate baldhead, a touch he leans into whenever I do it, even when he is driving. I felt the urge to do it, but I didn’t. It’s not because I didn’t want to; it’s because I was caught so off guard by his gift.

This was my slide down the banister, this was my carefree, this was my letting go of all the stresses of life — including all the medical trauma-caused compulsions and sensitivities that often weigh me down — and jumping off before reaching the bottom step.

~

I told this story to my family last Ramadan on the second day of the daily Arabic and Islamic Studies sessions I had committed to teaching them for the entire blessed month.

My students — Carl, who had embraced Islam just a couple of years before we married, and our two daughters — were tightly gripping pens, pencils and paper-filled clipboards and sitting on the eastward facing couch in our old living room, their backs to a more than nine-foot-wide window.

Outside that glass — not too far from where the dogwood trees on that street would whip themselves up into a shedding frenzy and drop into the air around us every spring, a near-blinding snow storm of soft, white petals — was a clear view of the spot where Carl and I had stood one Ramadan earlier, post-Fajr prayer, waiting in the dawn to catch a glimpse of the International Space Station (ISS) as it orbited about 240 statute miles above the planet.

I can still see the two of us now, occasionally pointing at false calls that sparkled in the early morning sky, our surroundings still more night than day, still more bluish black than anything else, but for the soft glow of the street lights and my white-socked feet moving this a-way and that a-way in the quiet — the quiet before the rabbits, cardinals, squirrels, feral cats, and even blue jays, would, sometimes, start brazenly parading through our yard; the quiet before our Jamaican neighbors directly across from us, the only other people of color on the block, would start their virtually daily routine of manicuring their lawn, often with the wife tirelessly pushing the mower and the husband building, with his bare hands, some new beautifying element to adorn their property; the quiet before the “For Sale” sign would become visible on the lawn of our elderly white neighbor, the neighbor who gave our girls Beanie Babies one year for no other reason than to express kindness in response to their bright-eyed innocence that I can only imagine must have reminded her of her youth, just like the real estate sign that would come later, marking her passing, would remind Carl and me of our youth, too, fleeting though it may be.

“Precious, look!” I’d suddenly heard my husband say.

His words sliced through those moments of quiet beforeness.

“I see it! I see it!” I’d shouted, as we both stared up at the scintillating technology shooting through the heavens above us.

And now, in our living room — a lunar calendar year later — there seemed to be just as much excitement about discovering new things.

“Why do we bow to God?” asked my youngest pupil, Nyota, referring to sajdah, the position where Muslims’ heads completely touch the floor during obligatory prayers, the position that too many unfamiliar with Islam believe — to Muslims’ absolute horror — is an act of bowing in prayer to the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ).

“Will you cover the cursive-like Arabic?” asked Carl, referring to the connected letters in Arabic that flow across the page from right to left.

“Mommy, what is the soul?” asked Mirembe, her inquiry following up on the discussion we had just finished about Muslims’ belief in life after death.

They were peppering me right and left with questions as we wrapped up class for the day. I was answering everything, swiftly, except for Mirembe’s question, which hung in the air a few beats too long.

“Mommy, what is the soul?”

I felt silly about my error. I had mistakenly used the word “soul,” without explaining its meaning, as if everyone knew exactly what it was.

Her words had been clear. Direct. No one would have been any the wiser that she had lost speech at a young age and only used sign language until the age of four.

Contemplating her question, I bought myself some time, fiddling with the dry-erase board of the two-sided easel we had been using for class, the chalkboard back of which our children, when they were smaller, used to draw Carl and me beautiful pictures there—in brilliantly-hued pastels—of people with unusually long arms and legs.

Now, on the eastern wall behind the easel, I could see my students’ shadows casting their positions, dutifully. Their silhouettes loomed there, on that wall, like a hand shadow show, a projection of the window– behind them — framing them there too, all a result of their couch-seated bodies partially blocking the sunlight that was forcing its way through the panes.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could also see my husband, head now hanging down, chin almost pressed against his chest to hide a half smirk curling from his lips, his expression exuding the familiar look of a parent whose young offspring has posed a question easily answerable to an adult, but stumping when trying to figure out how to respond to a small child.

He does not think I will be able to answer Mirembe’s question about the soul, I thought to myself then. And for a brief second, all my experience as a third-generation Muslim, born and raised in the Islamic faith, all my 20-plus years of religious study, research, writing and lecturing meant nothing.

I didn’t think I could answer the question for her either, for I had never really given much thought about breaking it down in a way a child could understand.

But then I remembered our drive, and I become animated and dramatic, calling on every sense memory of the event, dragging out the descriptions of the things I had seen, heard, felt along the way as Carl had just kept going and going, driving and driving that day in the Dodge.

As I recounted the joy ride, to my students, the girls began smiling those giddy smiles they have when they catch their father and me kiss or hug, those smiles they have right before they start running from one end of the room to the next with shrieks of excitement — the oohh’s and aahh’s right before they force their way into a group hug.

They knew this was about a deeper love.

I didn’t look at Carl then but I could sense him listening closer. I could sense the surprise emanating from him. I could see it in my mind’s eye.

I know him; I know this man.

He thought I hadn’t appreciated it, probably. He perhaps even thought I hadn’t noticed, perhaps. Maybe he thought his gift had been in vain. I just had been so moved; I had felt too vulnerable to express myself at the time.

“What daddy did,” I say to my students, Carl included, “that was from the soul, that part of him that will always be with him, in this life and the next.”

“It’s like when Mirembe watches over us,” I say, “whenever questionable songs pop up unexpectedly on the car radio, before we can change the station, and she thinks they might be inappropriate.”

“Mommy,” she always says, “I am worried about this music, I think it might be saying a bad thing.”

“She is concerned, always, about protecting our good,” I say. “That concern of hers,” I tell my students, “is from that part of her that is not just with her in this life, but will be with her in the next life, too.”

As I spoke about Mirembe I could see my six-year-old, Nyota, trying her best to hide her fear that I might have forgotten to give an example about the goodness of her soul.

“It’s like when Nyota brings me a new, freshly drawn picture each day, filled with hearts and words of love and affection to bring a smile to mommy’s face,” I say.

“Mommy,” she always says, “you are my best friend.”

“That,” I say, “is from her soul, that part of her that will be with her in this life and the next.”

“So we have to guard our souls,” I say, making purposeful eye contact with all of my students. “We have to guard our souls and make sure that we are doing good in the world, in this life, because our souls will be held accountable in the next life,” I say.

I can still see their faces now, all looking at me with their full attention, my students, sitting there on that eastward facing couch in our old house, surprised that I had been taking such close note of their actions and had translated them into a teachable moment. I had been surprised with myself, too, in those moments of storytelling, surprised that the essence of the goodness of who they are is what came to me then as a natural explanation for the soul.

It is not the perfect answer a scholar might give, filled with the literal and the technical.

It’s from the soul of our family.

It makes sense to us.

The End

~

Epilogue

“By the Soul, and the proportion and order given to it;

And its enlightenment as to its wrong and its right;-

Truly he succeeds that purifies it,

And he fails that corrupts it!”

—The Holy Qur’an, Surat Ash-Shams, 91: 7-10

One morning, this Ramadan, 1436/2015, our family sat on our prayer rugs, immediately following Fajr prayer, and we each spoke about what these verses mean to us. The sun had not yet risen, but we were as alert as if the shams was at its highest elevation in the sky.

And it was a truly special feeling to not be alone in this search for understanding, to hear the many different perspectives, from male to female, from the youngest to the oldest, from learned to that which comes naturally from our fitrah, which we are born with.

And it was a truly special feeling to be surrounded by so many loving souls.

~

Precious Rasheeda Muhammad is an author, lecturer and researcher on Islam in America and the full diversity of the American Muslim experience. She lives in Virginia, where the struggle for freedom of religion in America has some of its deepest roots. Her blog, Muslim History Detective, is hosted on Patheos Muslim. This story is adapted from a longer version of an unpublished piece. Find her on Twitter @preciousspeaks