By Yūsuf ‘Abdul-Jāmi’

Verily, tyrannical rulers will come after me and whoever affirms their lies and supports their oppression has nothing to do with me and I have nothing to do with him, and he will not drink with me at the fountain in Paradise. Whoever does not affirm their lies and does not support their oppression is part of me and I am part of him, and he will drink with me at the fountain in Paradise.” (Jāmi’ al-Tirmidhī)

“It does not matter. Let a man help his brother whether he is wrong or being wronged. If he is oppressing others, then stop him for that is helping him. If he is being oppressed, then help him. (Ṣaḥīḥ Bukhārī & Muslim)

– Prophet Muhammad, The Blessed Messenger of Allāh (saw)

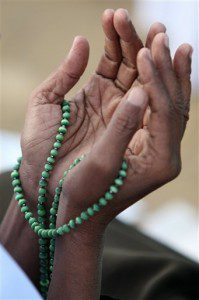

I am accustomed to seeking solace from scenes of black death and dying in the depths of dhikr where my heart has hidden what hope I have left that our souls can be healed. I am accustomed to it because prayer and remembrance have been the refuge of my forefathers and foremothers ever since they first tasted and then toiled on the Ames plantation in southwestern Tennessee. My weary heart was introduced to the Islamic forms of remembrance through the guidance of shuyūkh and scholars at some of the most beautiful and beneficial spiritual retreats I’ve ever attended.

Some of these shuyūkh, and their students, have demonstrated a sincerity about understanding the realities of racism that I wished was more widely shared.

But this time my hands are wet with tears and the prayer beads slip past my fingers too easily onto the floor. And as I strain to hear the guidance that I’m certain will come from the descendants of saints, scholars and servants of the sacred traditions of Sunni, Shia and Sufi, silence returns to sit besides me and smile at my pain. As black bodies struck the streets, a familiar silence strikes me again and again. I recognize it as the same silence that emanated from the majority of non-black Muslims when black people, who were experiencing the harshness of injustice, called out for solidarity and support.

Among the words I do hear, mostly from their followers, students and admirers, are admonitions to ignore the suffering on the streets, the torrents of tears and the terrorism of tyrants that claims black innocents. Condescending caution, clothed in spiritual speech, seeks to calm me lest my anger at justice denied cost me both peace and paradise. I hear that I should have more patience and less anger. I hear that we aren’t worthy of solidarity because we respond too violently, too emotionally to oppression.

I hear that we don’t have any leaders worth following and that if we would only be more like Bilal, more like “post-Hajj” Malcolm, more like the Martin that dreamed and less like the Martin that marched. I hear that as Black Muslims we should turn our efforts towards being less black and more Muslim, as if Muhammadan resemblance and blackness were mutually exclusive.

If certain inheritors of the Prophets have not inherited the urgency of the Prophetic injunction to prioritize the pain of the oppressed and aid their struggle against the slaughter in our streets, what spiritual nourishment will starving souls find? If more shuyūkh, like the perceptive and patient souls I’ve personally encountered, aren’t willing to fully engage black suffering and our legacy of a liberating black spirituality, on their own terms and as divine sustenance for the sons and daughters of slaves, how will minds and hearts ever be unshackled?

Prayer beads don’t stop bullets and the mercies of mawlids don’t suffice to protect innocents from manifest malevolence. Dhikr can and should be done while, not instead of, defending the dignity of the disenfranchised. Black American Muslims come into increasing contact with traditions of taṣawwuf in times of such urgent turmoil, these traditions must offer forms of remembrance that respect the balance between sanctity and struggle, represented to varying degrees of effectiveness by the lives of El Hajj Malik El Shabazz, Warith Deen Muhammad, Ahmadou Bamba, Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman.

Prophetic resemblance within the African-American spiritual context is most often predicated on how effectively this synergy is maintained during our struggle for existence against all forms of extermination. Our rituals of remembrance include a tradition of scholarship, seeking the peace and blessings of Allāh upon our beloved Prophet ﷺ, and continuing the best traditions of our righteous ancestors’ sacred struggle.

Unless sacred spaces offer solidarity and sanctuary, not just a sanctity more suited to sleepwalking past beaten bodies than struggle, what refuge from slaughter can former slaves find from terror and trauma? When some shuyūkh and their students silence the oppressed by suggesting that they occupy themselves with sanctification while soldiers of post-racial slavery slam their bodies to the streets with bullets and bombs, where are we to search for saints?

Calling for the oppressed to take up the inner jihād of Prophetic remembrance while abandoning them in their struggle for justice, which is the essence of Prophetic resemblance, is a betrayal of both. Shaming those who are suffering by asserting that their sins are the reason they are being slaughtered gives moral sanctuary to the supremacist footsoldiers of shirk.

Insisting on silent suffering as a requisite for salvation, on supplication as a substitute for struggle and demanding deference to dogma or to Muhammadan descendants, whose silence is indicative of both disengagement and distance from the black and Muslim experience, as conditions of Divine deliverance from oppression is to misrepresent the meaning of mercy.

May Allāh ﷻ preserve His saints, scholar-warriors, steadfast servants, and the legacy of His Prophets, peace be upon them all. And May He strengthen, encourage and deliver the oppressed and persecuted among his servants from every affliction and injustice into His mercy and everlasting peace.

O Allāh, make me better than what they think of me, and forgive me for what they do not know about me, and do not take me to account for what they say about me (Allāhumma-ja’alnī khayran mimā yaẓunūn wa-ghfir lī mā lā ya’lamūn wa lā tu’ākhidhnī bimā yaqūlūn). —Abū Bakr aṣ-Ṣiddīq

Yūsuf ‘Abdul-Jāmi’ (Jimmie Jones) was born and raised on the south side of Chicago. He is currently serving on the board of the Muslim Wellness Foundation to reduce stigma associated with mental illness, addiction and trauma in the American Muslim community. As a Muslim, an African American and a father with ADD, he engages in advocacy efforts around mental health, race, culture and spirituality. He currently lives in Maryland with his wife, an educator and a doula, and their three children. A version of this article originally appeared on SapeloSquare.com.