Today I share another article from a developing series on expanding perspectives presented here starting last month with two wonderful academic guest posts on the topic of race in American Buddhism (“Race Matters…” and “The Dukkha of Racism…”). Yesterday’s interview with Tenzin Pelkyi of the Tibetan Feminist Collective, though developed alongside the series, further expands our awareness of the Buddhisms lived and practiced in America-and elsewhere-today.

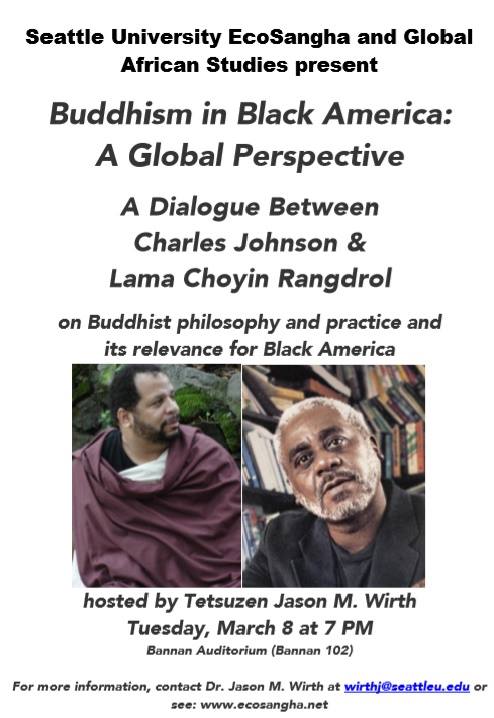

Today’s post is longer than earlier posts but worth every word. Lama Choyin Rangdrol has been a pioneer in discussions of race in American Buddhism since his 1998 and published Black Buddha: Changing the Face of American Buddhism in 2000. I recall contacting him in my early blogging days in 2004 or ’05 and receiving a kind response and was delighted to reconnect with him earlier this year. The following is from a forthcoming book expected out this year, and he will be appearing with Charles Johnson to discuss Buddhist philosophy and practice and its relevance for Black America March 8 in Seattle (see bottom for further details).

Preface

This book is for African Americans interested in practicing Buddhist meditation. The approach is based on a new kind of intentional community building plan. One that banishes beliefs and practices historically used to corral, enslave, and exploit the Black Mind. In fact, the pages ahead offer a Buddhist plan to end the vestige of slavery in African American minds forever. The goal is to cleanse the Black psyche with the same diligence one washes chitterlings.[1]

The non-African American reader is forewarned these pages are written in 21st Century African American survival language. The discourse lacks obligatory niceties for those whose heritage has never known the butt end of racism, forced global isolation, and servitude under enslaving religions in Africa and America.

I promised this work to my African American friends a decade ago. It’s for them. Some gave up hope it would be completed. I never did. So here it is.

A similar promise was made to my Untouchable Buddhist friends in India. I’d promised to establish a link between their human dignity movement and African America. The words contained herein are humbly offered as fulfillment of my promise to both communities.

………………………………

Introduction

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. acknowledged the inevitable intersection of America and India’s oppressed masses during his 1961 speech, The American Dream:

“The destiny of India and the destiny of every other nation is tied up with the destiny of the United States and the destiny of the United States is tied up with the destiny of India.[2]

Despite King’s insight, Buddhism was never used to advance the social or spiritual condition of African America. Why? Because the politic of America’s Christian Civil Rights Movement was bent on establishing its own legacy. Buddhism and other alternative spiritual paths were suppressed.

Nonetheless, according to King’s 1961 statement, today’s African American School of Buddhism stands on his visionary ground. The school’s philosophy is a 21st century follow-up to his foresight. A philosophy that, for the first time in human history, offers Black America an opportunity to divest itself of beliefs used to enslave them.

Today the enduring legacy of slavery’s vestige, Jim Crow, urban violence, misdeeds in the Black pulpit, and death of aging Civil Rights leaders mark the end of an era. Black America’s spiritual destiny is in the wind. The opportunity for African American Buddhist Awakening rests on its wings.

In order for Buddhism to land squarely in the mind of Black America, it must penetrate every nook and cranny of African American life. It must give voice to the unmentionable, say the unthinkable, be willing to shock sensibilities, and geld conventional wisdom. While pressing forward it must also avoid forces that dragged Black America down in the first place. This is a monumental task that will take millions of Awakened African Americans to accomplish. An entire new language must emerge.

The glossary at the book’s end points out words that had to be invented, interrogated, assaulted, and at times obliterated. Flogging words was necessary to reveal Standard English is itself a hindrance to the Black Mind’s Awakening. This work dares to confront the English language’s formidable obstacle to excavating Black truth. It empowers the African American Buddhist to explore taboo identities and beliefs, including the inalienable right to express a Black and Buddhist opinion at the same time. If I’ve erred I did so in the name of preserving my sanity, and that of the Black reader.

The phrase “enslaving religions” is used copiously. But this work is not about them. Nor is it a competition with what they represent. There’s no need to compete against other religions. The struggle is with words. Words are the gatekeeping culprits of the Black Mind, not faiths. Besides, unlike enslaving religions, Buddhism has never enslaved a single human being in Africa or America. Why should it compete against those that have? Buddhism’s lack of mass human enslavement makes it as pristine to the African American mind as freshly fallen snow. Enslaving religions’ misconduct toward ancient humanity is their burden to bear. It has nothing to do with the Buddhist mind or way of life. This is beyond dispute. Competition is nonsensical, or at the very least a distraction.

There is no need to wage an argumentative war with Christians in a nation founded by them on the tenets of their religion. Because of slavery we, Black America, are forever bound to the Christian ideal. Even if Christianity were put asunder it would not be good for our country. African America’s body politic cannot win a battle against its Christianized spine. More to the point, African American Buddhism is ruggedly self-sustaining on its own. It can honor its community’s Christianized roots while simultaneously radiating a productive influence in the world.

Everyone knows Buddhist peace is already practiced in African America. What they may not know is Buddhism gained Black attention a while ago. Admiration for Buddha surfaced significantly during the 1920’s Harlem Renaissance. You’ll read about that ahead. But before delving into history, this work offers insight into translating traditional Black convention into the cultural language of Buddhist Awakening.

Commingling Buddhist pragmatism with everyday African American life is essential to the process. By pragmatism I mean ‘keeping it real’ with grassroots African Americana. This includes but is not limited to political necessity, academic rigor, addiction to materialistic bling, stress of incarceration, quiet nights of pillow talk, mind numbing poverty, social illiteracy, street corner debates, the paper-bagged ‘fouty’-ounce, “Yo Mama” battles, small talk at beauty salons, back rooms in gangster mansions, Black religious activism, the “N” word, sports talk, anti-Buddhist sentiments, HBCU mis-education on Buddhism, the pot of chitterlings next to the neck bones at Juneteenth celebrations, before dinner talk at the soul food restaurant, video game trash talkin’, bootyliciousness, Greek hazing, slappin’ down d’em bones, the cutting wit of the pimp cup, cuttin’-up at the barbershop, rumblin’ the 808, the butt end of Black comic’s jokes, Black nerd conversations, HaTeRzville, Ivy League hissy fits, Black media punditry, Strait Outta Compton Buddhahood, sippin’ the smooth cool of Hennessy and Cristal, soul desiccation of long-term unemployment, Black Buddhist Lives Matter, twerking and even while zombies attack Black neighborhoods if necessary. In short, Buddhism in Black America must move seamlessly among the people and express ideas worth listening to.

Understanding Buddhist pragmatism is necessary for the sake of healing the injury of slavery. One way or another the mental landscape of slavery’s vestige must be abandoned. If not, the Black Mind will forever remain open to slavery-born foibles.[3] A community warring against itself, religiously or otherwise, is futile. For example, everyone knows anger is pathologically rampant throughout Black communities. Anger that once fueled social change festers among us today like a centuries old wound. People are sickened by it. Our children are killing and being killed by it. Even though one may think anger is a predicament of poverty, the fact is Black anger burns like hot coals in the belly of Black rich and poor alike.

Buddhist meditation on the other hand is very new to African America. It’s cool and fresh, yet loaded with the wisdom of ages. It’s seen civilizations, religious founders, and the nobility of their doctrines come and go. Buddhism’s sanguinity is not derived from the babbling brook of recent times. Its mighty river spans millennia hewn deeply into the valley of human peace consciousness.

Buddhism is the symbol of a better way because of what believers in its teachings have not done to the African Continuum. Buddha’s eyes are soft with love and understanding. He sees the suffering of all sentient beings. His heart is tender with mercy. A single palm upraised through time cautions all who look his way to guard against dehumanizing themselves and others. In the best of times, Buddha’s bounty offers the highest human ideal. During challenging times he offers the same high ideal rather than wrath or vengeance. This alone is worth contemplating deeply.

For an African American, turning one’s mind to Buddhism is victory unto itself. For how can African America suffer defeat by adopting a faith that’s never enslaved its people? Is not exiting enslaving religions victory? Yes, of course it is. Especially if your ancestors were enslaved by your birth religion’s believers. It’s no different than exiting a burning building. Regardless of what one believes, the act of exiting saves your life. For that reason African Americans Buddhism is a straightforward survival plan.

Can African America benefit from learning to survive the next twenty-five hundred years as Buddhism has already done? Again, yes, of course it can. The details of acquiring such insight are invaluable.

This book from cover to cover makes the case. It’s written by an African American Buddhist teacher for his people. Anyone who traverses these pages is wise to take what is read to heart. They deal with liberating the Black Mind without need for racial invective.

Readers unfamiliar with the African American experience may have to decode our culture along the way. Decoding African America’s Buddhist complexity is necessary to grasp the totality of this book’s meaning. That’s fair. African America, for sake of its survival, has spent generations decoding conquest culture. Fittingly, words and perspectives Anglicized Buddhists would never allow on the published page lay ahead. The concepts are audacious, inflammatory and sometimes painfully blunt to those who’ve never considered what an enslaving religion is.

Prepare for a rousing read that’s rare in Buddhist America. A new course is intentionally chartered here. A game change to say the least. Right Speech henceforth is defined as the inclusion of Black America in the global Buddhist experience, invited or not. Forces that’ve excluded the African Continuum from global Buddhism’s annals deserve the mental wake-up call this work delivers. It’s long overdue. For that reason alone, Buddhists who thirst for alternative voices will find this work’s departure from the norm refreshing.

The language is different. It riffs on the symbiosis of 1) Western Buddhism’s ills, 2) Afro-Buddhist[4] history in Asia, and 3) the history of Black America. Commingling these and other themes is essential to slipping and sliding the Black Mind around the tight corners of Buddhist Occidentalism.[5]

It doesn’t matter if African Americanized Buddhist dialogue falls on the deaf ear of America’s Buddhist elite. They are not the whole of humanity. Even the most privileged among them knows the freedom of African American improvisation mentallyenlivens the listener’s. In like order, humanity will respond favorably to Buddhist innovation African American style. Some will laugh, some will cry. Others will squirm uncomfortably with furrowed brow. A few will be driven mad with celebratory joy. Despite it all one thing is certain: If not for improvised African American cultural coding of the Buddhist idiom, everything meaningful about it would be dismissed or assimilated into oblivion by America’s dominant Buddhist culture.[6]

Readers who find kinship with the voice of this work should expect bewilderment to arise from what has taken so long to be said. The language of freeing Black minds demands the ‘language of oppression’ be confounded. Everyone understands this. Make no mistake. An African American turning to Buddhist meditation is doing so to rescue his or her immortal soul. They realize the religious beliefs used to enslave human beings in Africa and America are lodged deeply in their psyche. For them the Underground Railroad of Buddhism is an idea whose time has come.

Revelations in this work were inspired by a multitude of against the stream thinkers. James Baldwin deserves credit for his masterful use of English as a weapon against those who brought it to the fight. India’s Bhimrao Ambedkar’s[7] fearless belligerence in the face of incalcitrant Casteism was also deeply motivating. No less was the influence of Shakespeare’s dramatic flair for revealing sinister plot through subtext. Kick-ass Gore Vidal inspired boggling the mind of naysayers. Ram Das, Black Elk, and Castaneda granted permission to reveal the visionary mystic experience. Belgian-French female explorer Alexandra David Neel’s abandonment of convention kindled the adventurous spirit. The rhapsodic poetic of Dylan Thomas gave permission to write in streams of consciousness. Van Gogh’s Pointillism brought home the importance of the period at sentence’s end. Slave insurrectionists Turner and Vesey contributed the rabble-rouse spirit of unmitigated gall. My Buddhist teachers, and of course their teacher, Buddha, calmed my spirit enough to survive the writing process. Complexity of these contrasting influences helped me to find my voice. I alone am responsible for my fly-wisp’s swoosh at the pesky nuisance of Western bias. Just as Trungpa acknowledged responsibility for his antics, I am responsible for this tome’s impertinence.

The subtext is a dialogue between worlds that know little of one another. The Indian[8] reader knows nothing of being taken downtown in Bid Whist. The African American reader knows little of, “Panatipata Veramani Sikkhapadam Samadiyami.” Likewise, the Anglo Buddhist reader knows little of being shocked senseless by the “N” word used in reference to their humanity. Their’Buddhists of Color‘ allies know little of working exclusively for the uplift of Black America. Many still have not come to grips with the fact Buddhism is an of color movement (See Figure 3). It doesn’t matter. This book speaks forthrightly to African Americans within their ranks in a familiar language. It must. Egalitarianism, having nothing to do with race or the ugly side of racism, demands American Buddhism’s glass ceiling and limited views be shattered. New meanings, recognitions, and pathways will arise from the ensuing chaos. Let the debate begin.

Providence, not a lone author, beckons this book to Awaken Black America. The work to be done is serious. No one born into the mental or spiritual imprint of slavery need die there. The survival-savvy Black Mind is intelligent enough to change the course of its subjugated fate. All it needs is a constellation of ideas that inherently thwart re-inscription of slavery’s vestige. Buddhism is the natural place to evolve such ideas.

Ubiquitous meditation, The Buddhist Solution, is African America’s liberative currency of the future. However, as an agent of change, this book is limited. It can only offer the chapters ahead. Its case for Buddhist liberation ends with the last word written. You, the reader, are the jewel in African America’s lotus. Your mind, your heart, the totality of your humanity and every moment between now and your death are the vehicle of liberating generations to come. You must inspire yourself and others despite slavery’s demons urging otherwise. This book is your trustworthy guide. With it in hand, “Escape to Buddhism” becomes one of the most powerful phrases ever uttered in African America.

As descendants of slavery, our plan must be to engage in a Black Buddhist meditation experience like no other. Have no qualm about dealing with the issue of escaping what was done to your ancestors’ minds. They spent generations of harsh treatment under dehumanizing conditions. They were worked to death in circumstances unbefitting human existence. Though eventually freed physically, no one came to liberate them from mental, emotional, or spiritual subjugation. The abuse they suffered should not be forgotten. Their story is the story of Black America.

As free-born descendents of African American culture we meditators have a job to do. It’s our job to peacefully prune today’s tree of Black spiritual life. When we face this truth, we have to admit enslavers did the first pruning. Their institution of slavery changed African religion into Christianity. Did they not? However hurtful and shameful revisiting slavery’s wound may be, we can find solace in the fact our ancestors survived. Did they not? Yes, they did. Well then, who’s to say today’s African America cannot survive meditative pruning of its own religious culture?

There’s no need to make a better case than what slavery has already proven. Our very existence is proof profound change of Black religious culture, en masse, is not terminal to the Black psyche. For that reason, in essence, there’s nothing to be afraid of. Those who insist on living in fear and frightening others should move to the back of the spiritual bus where fear belongs. Whatever folks outside the African American community think, the use of meditation to liberate the Black Mind is ours, not “theirs” to cultivate.

The premise of our work is found in a simple anecdote about Buddha’s life:

Hindu prince, Shakyamuni, realized his birth religion stood in the way of his Awakening. He sat by a tree, thought about it, mentally escaped his birth religion, and thereby changed the world.

Every meditative action in Black America need only be an expression of this simple approach.

If the heterogeneous mass of Black America individually uses the young prince’s approach to Buddhist Awakening, a 21stCentury Age of Enlightenment Black America can call its own will arise. Its potential is the likes of which humankind has never seen. If asked how can you possibly believe Black America is capable of achieving its own Age of Enlightenment, respond, “How can you not?”

Any man or woman interested in Buddha’s approach is capable of Awakening. Africa American Readers of these pages are guaranteed to taste the fruit of yonder shore—a place where the Negro spiritual,[9] Buddhist Doha,[10] and Refuge Chant [11] are one. Devoted African American Students of meditation will sip the nectar of self-emancipation as they study these pages in earnest.Practicing African American Buddhists will accomplish quiescent realization as they ponder why so many Buddhas in Asia look like us. The meditative adept will dissolve into light having completed the practice of profound openness to this work. Skepticsquest to find fault in the Buddha will Awaken them without meditation. The Non-believer will Awaken through his or her determination to ensure Buddhists live as they say they believe. And African America, having healed its innermost injury from slavery, will inspire the world.

May all who read and practice what lay ahead Awaken; each in their own way.

© LCR

To see the original version of this post, which is part of an upcoming book, visit http://africanamericanbuddhism.blogspot.com/. For more of Lama Choyin Rangdrol’s publications, visit his page at lulu.com. To see him live next month with Charles Johnson, see the below announcement:

[1] chitterlings – [pronounced chit-lins] Boiled hog guts fed to slaves as a cheap food requiring meticulous cleaning of fecal matter; known for their noxious in odor while cooking; today an African American culinary tradition.

[2] The American Dream, Dr. Martin Luther King, Lincoln University, June 6, 1961.

[3] foible – weakness in character, faults.

[4] The aspects and images of Buddhism in Asia that reflect the African Continuum.

[5] Occidentalism: Characteristics of Western European Countries, and Anglicized America.

[6] dominant culture – a relatively small yet elite control group in society who establish norms as a means of perpetuating their dominance; a subject of much discussion in the following pages.

[7] Bhimrao Ambedkar – Untouchable Indian scholar, lawyer, political leader, and orator noted for his blistering critique of Casteism. Chair of the Drafting Committee for the Indian Constitution. Buddhist convert, 1956. Popularly called: Babasaheb. http://https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B._R._Ambedkar

[8] Ambedkarite – Buddhist of India who follows the philosophy of Ambedkar.

[9] Christian songs created by enslaved Africans in America.

[10] Doha – Spontaneously composed spiritual songs of awakening sung by male and female Buddhist adepts.

[11] Refuge chant – vow to take safe haven in oneself, instead of a creator whose believers spent centuries enslaving Black minds. “One truly is the protector of oneself, who else could the protector be? With oneself fully controlled one gains a awakening which is hard to gain.” Dhammapada