Recently I read G.K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, A Nightmare (1908), a roller-coaster of a novel, full of surprises and thought-provoking theological reflections. (It is also, happily, one of the public domain titles available for free on Kindle.)

I don’t want to summarize the book because The Man Who Was Thursday is best read the way I did — totally fresh. Going in, I knew Chesterton’s work, or at least I had read Orthodoxy, his most famous work. But I knew almost nothing about this particular book; thus I was properly unprepared for its twists and turns.

I don’t want to summarize the book because The Man Who Was Thursday is best read the way I did — totally fresh. Going in, I knew Chesterton’s work, or at least I had read Orthodoxy, his most famous work. But I knew almost nothing about this particular book; thus I was properly unprepared for its twists and turns.

The Man Who Was Thursday revolves around Gabriel Syme, a secret agent of Scotland Yard who infiltrates a violent anarchist group. The “nightmare” genre gives Chesterton artistic license to take the novel in increasingly absurd and visionary directions, including the book’s final chapter, which features a stirring theological dialogue on the meaning of suffering.

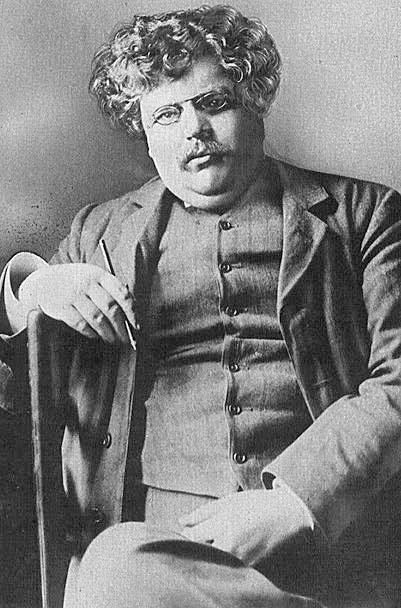

Chesterton was a phenomenally prolific writer, taking on everything from theology to fiction to literary criticism. Befitting his work as a newspaper columnist, he wrote constantly. His personal image enhanced his fame: a giant of a man, six foot four and three hundred pounds, Chesterton was rarely seen without a cape, cigar, and swordstick.

Chesterton increasingly gravitated toward traditional Christianity, and in 1922 he converted from high-church Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. As with C.S. Lewis, an Anglican influenced by Chesterton’s writings, evangelicals may not always resonate with the specifics of Chesterton’s malleable theology, but most will love his apologetics and criticisms of the modern age.

This is not to say that it is always easy to understand Chesterton, especially in The Man Who Was Thursday. Chesterton scholar and annotator Martin Gardner notes that one early reviewer of it ‘commended Chesterton’s “brilliant prose” but put the book down “with no earthly idea” of what it was all about.’

My friend and Baylor colleague Ralph Wood writes in his Chesterton: The Nightmare Goodness of God (2011) that a new view of The Man Who Was Thursday‘s meaning strikes him every time he reads it. Although Wood concedes that this could be because the book is a bit disjointed, he mostly thinks it is because “great works of art are subject to diverse and even contradictory interpretations.”

How wonderful to find a book that is both theologically sophisticated and a great read. Put The Man Who Was Thursday on your summer reading list.