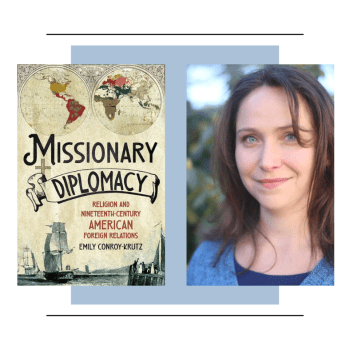

Reuben Torrey and Henry Crowell are the two key figures in Timothy Gloege’s outstanding Guaranteed Pure. In his book, Gloege develops a rich analogy between the rise of corporate advertising and the rise of American fundamentalism.

Crowell grew up in a Presbyterian family, then was taken with Dwight Moody’s revival encouragement to “dream great things for God.” Crowell did not decide to become an evangelist. Instead, he determined to make money to be used for God’s service. And he proved adept at making money.

Crowell grew up in a Presbyterian family, then was taken with Dwight Moody’s revival encouragement to “dream great things for God.” Crowell did not decide to become an evangelist. Instead, he determined to make money to be used for God’s service. And he proved adept at making money.

In the 1880s, Crowell purchased the Quaker oat mill in Ravenna, Ohio. The mill had a new kind of technology that cut oats of higher quality than competitors, but the true key to Crowell’s success had little to do with the oats. Instead, he developed the Quaker brand.

Prior to Crowell, customers expected to shovel oatmeal out of large barrels without paying too much attention to its quality. They depended on their grocer (who depended on his wholesaler) to purchase a decent product.

Crowell made money not by cutting costs but by persuading customers that it was worth it to buy only Quaker Oats. He sold them in two-pound sealed package — no more shoveling oats out of a barrel. The seal on the package, Gloege writes, “was an implicit contract with the consumer for oatmeal that was guaranteed pure.”

Back to Crowell in a minute.

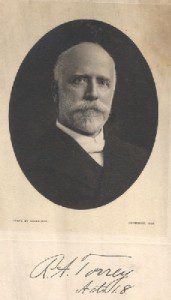

Reuben A. Torrey would be more famous in his own right if the peak of his evangelistic success did not come sandwiched between Dwight Moody and Billy Sunday.

Torrey also had his life changed at a Dwight Moody revival. At the time, Torrey considered himself “an avowed liberal” and went there simply to see Moody for himself. Instead, he wanted to know the secret to the relatively uneducated Moody’s power. Torrey exchanged his taste for higher criticism for a faith in the “plainness” of the Bible, went into the ministry, and devoted himself to reaching working people.

Torrey’s theology of the Holy Spirit both inspired many other evangelicals and revealed some fissures within evangelical ranks. Torrey spoke of the Baptism of the Holy Spirit subsequent to salvation that made Christians effective in “testimony and service.” No spirit, not power. Believers could access that spiritual power by surrendering themselves to God’s “control and use.” Faithful living enabled ongoing access to spiritual power.

Torrey’s theology of the Holy Spirit amounted to something like a proto-Pentecostal Holiness Christianity. For a time, he preferred to live by faith on unsolicited contributions rather than undertake any active fundraising for his work. He also, at least for a time, believed that Christians should eschew doctors and rely on faith for physical healing.

This produced perhaps inevitable disappointment, doubt, and tragedy. If faith would enable access to power and blessings, when those blessings did not occur, the only reasonable explanation was a shortcoming of faith. So if the money did not come in as needed, then Torrey must have made some sort of spiritual mistake.

In 1898, Torrey’s eight-year-old daughter Elizabeth fell ill with diphtheria. An antitoxin would almost certainly have cured her. Instead, Torrey chose to pray. According to Gloege, Torrey was so faithful that God would answer his prayers that he spent the rest of the evening drafting summer landscaping palns. When Elizabeth worsened, Torrey panicked and called a doctor who gave her the antitoxin. But too late. After Elizabeth died, Torrey blamed himself, but not because he had not called the doctor earlier. He blamed himself for his unfaithfulness.

Faith healing was a major point of controversy in Chicago at the time, and when Torrey’s written defense of his actions became public knowledge, it was bad publicity for Moody Bible Institute.

One reason that men such as Crowell embraced dispensationalism was because it provided a respectable (in a sense) solution to the scandal of Torrey’s beliefs. Dispensationalists generally believed that miracles had ceased with the age of the apostles. Certainly, God could always intervene. God was sovereign. But normally God did not do so. “In other words,” writes Gloege, “…God typically worked through ‘ordinary’ means … most miraculous claims were counterfeits, either figments of a misguided imagination, ‘natural causes’ mistaken for miracles, ‘mind-cures,’ or perhaps even demonic manifestations.”

Thereafter, evangelicals would go to the doctor. They would actively raise money. They would systematically plan evangelistic campaigns. Of course, many already had done these things, and evangelicals had throughout the nineteenth-century fought theological battles from the competing perspectives of Crowell and Torrey. It is not that evangelicals abandoned a sense of the supernatural or the miraculous. Any conversion was a miracle. Healing through the work of physicians and prayer was still attributed to God. But it could be supernaturalism shorn of fanaticism, or perhaps a coming to grips with a “disenchanted” world.

Crowell and Torrey could not coexist at the helm of Moody Bible Institute. Torrey eventually lost influence, and Crowell guided the institution for decades to come.

What Crowell wanted to do, and could not quite achieve, was to make MBI the fundamentalist equivalent of Quaker Oats. (Crowell was a major backer of The Fundamentals project in the 1910s). If a church or committee engaged someone from Moody to run an evangelistic campaign or as a pastor, that church should feel assured it was getting somewhat free from the contagion of modernism, just as a consumer could count on those oats to be “guaranteed pure.” And Crowell was probably at least mostly true to his word. Moody was a fundamentalist bastion against modernism.

But a container of Quaker Oats could satisfy nearly anyone who wanted oatmeal. Branding could only take MBI so far, because so many people wanted different varieties of Protestant Christianity. Did you want fervent premillennialism? Or a more irenic evangelicalism? Crowell and like-minded administrators tried to steer clear of anything that would either compromise MBI’s purity or narrow its appeal, but it was a tightrope. In fact, it proved much more difficult than it had been back during Moody’s lifetime.