After various children’s bibles, I first read the Good News Bible. Since the Bible turned out to be more interesting than most sermons and choral anthems, I am pretty certain I got through most of it in church services as a boy. Who wouldn’t find the narratives of Genesis both shocking and riveting! I then spent my high school and college years with the NIV. At seminary (Louisville Presbyterian), the NRSV was standard, and I still use the NRSV for classroom study.

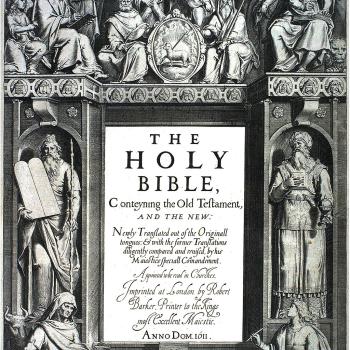

I have never spent much time with the King James Bible. I increasingly recognize this lack of familiarity as a great deficiency when it comes to studying the history of Christianity in the United States. When reading the letters, journals, and speeches of early-nineteenth-century Americans, I frequently encounter language that I later realize is from the King James Bible.

For instance, I recently dipped into the writings of Simon Hough, a stridently anticlerical preacher in western Massachusetts who believed that most of the world’s Christians wore the mark of the beast predicted in Revelation. They were Catholics who paid their priests money in return for the forgiveness of sins, or they were “sectaries” who enriched scheming Protestant pastors in return for assurances of salvation. Hough had rough words for Universalists, Methodists, Baptists, New England’s “New Divinity” preachers, and Shakers, and nearly everyone with college or seminary training. In his 1792 Alarm to the World, Hough warned that Christ would come in this generation “to reckon with the fat cattle.” In A True Gospel Church Organized and Disciplined, Hough criticized “hirelings and priest craft … Who teach for lucre, not for love.” The last phrase alludes to several passages in the New Testament (such as 1 Peter 5:1 and Titus 1:11) that condemn teaching “for filthy lucre.” The NRSV renders this “sordid gain.”

In my studies of nineteenth-century Mormonism, I regularly encounter phrases from the King James Bible (this is also true in studies of contemporary Mormonism, because the LDS Church has published its own edition of the King James and declared in 1992 that “in doctrinal matters latter-day revelation supports the King James Version in preference to other English translations”). For example, by the early 1840s it became common for writers to describe Mormons as “a peculiar people.” Whether they meant “odd” or “distinctive” by that appellation, it did not especially bother church members, as the phrase appears in 1 Peter 2, which identifies Christ’s followers as “a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a peculiar people.” The phrase sounds much stranger to contemporary Americans, who might read in the NIV of “God’s special possession” (instead of “a peculiar people”).

A lack of familiarity with the King James is a major handicap when reading the writing of nineteenth-century Americans. Perhaps graduate students in U.S. History should add the King James Bible to their comprehensive exam lists (which are usually limited to secondary sources). But there really is no quick way to overcome this handicap. Even reading the KJV once through would not give one the familiarity that earlier generations of Americans gained from regular encounters through private reading, church services, and the abundant allusions to its texts in public discourse and writing. I know that I am missing a host of references, though. When I encounter a turn of phrase such as Simon Hough’s, a quick search often reveals it to be from the King James.

I suppose if my church had put the King James in its chair racks instead of the Good News Bible, I might be a more perceptive student of early American Christianity. On the other hand, those sermons might have more successfully competed for my attention.