For all their humility and reputation for being “the quiet in the land,” Mennonites sure do get a lot of press. This past week during the Mennonite Church’s biennial convention in Kansas City, they made news for passing a document entitled “Forbearance in the Midst of Differences” and passing a resolution against drone warfare. “Weird Al” Yankovic praises Lancaster County Mennonites for living in an “Amish paradise.” Garrison Keillor tells Mennonite jokes (“What does it take to keep an Amish woman happy? Two ‘men-a-night.”). Methodist bulldog Mark Tooley worries that Mennonites are getting “aggressive, demanding that all Christians, and society, including the state, bend to pacifism.”

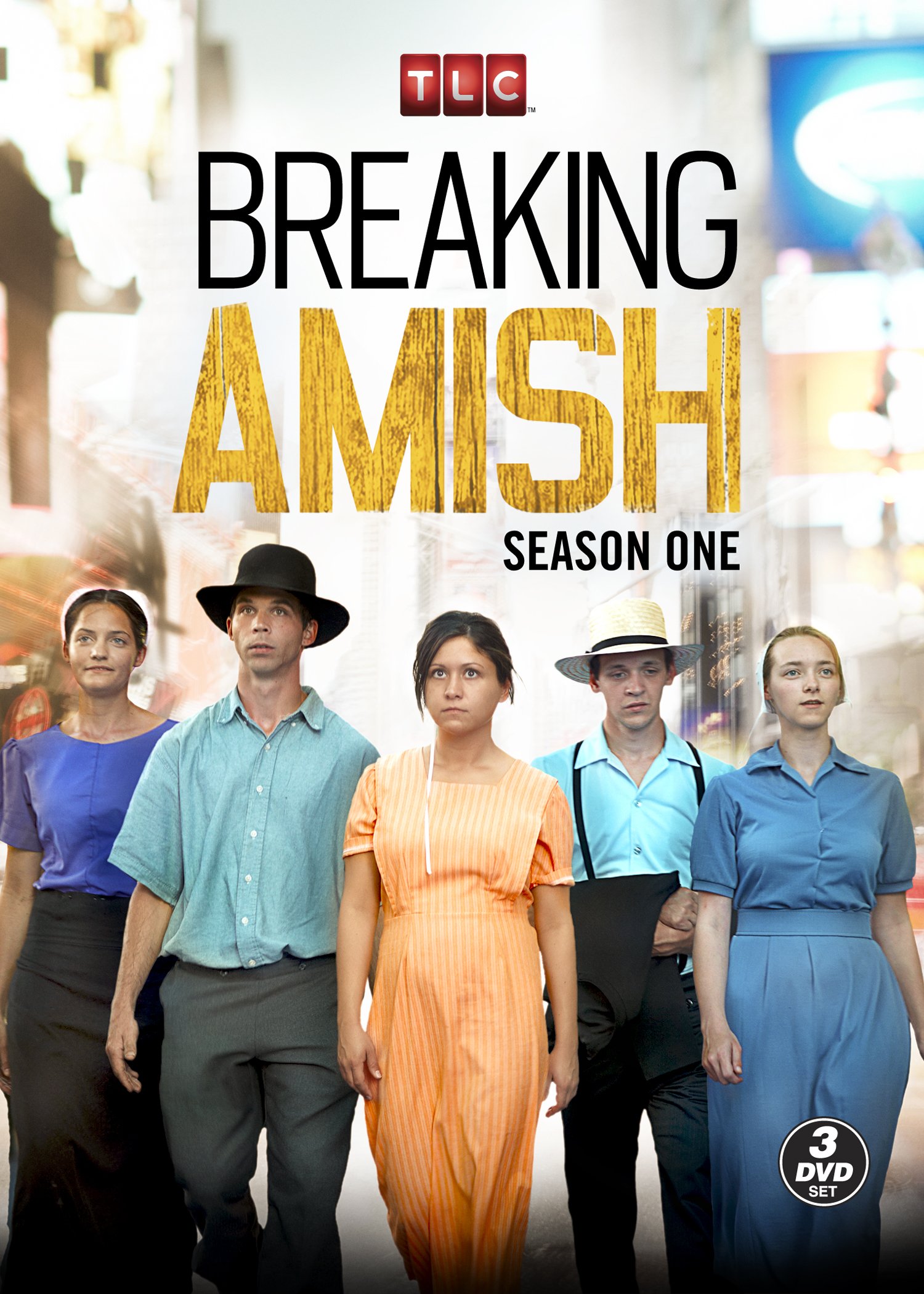

And the list goes on: a Washington Post commentary on Shoofly pie, a painting of a Mennonite minister by Rembrandt; an appearance in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest; Joseph Heller’s Catch-22; Harrison Ford hiding out among the Amish in Witness, cameos in The Office, The Simpsons, Modern Family; and entire shows Breaking Amish and Amish Mafia. I’m sure Mormons and Catholics get their share of attention, but they’re a lot bigger. According to Steven Carpenter, author of the fascinating new book Mennonites and Media, “punch above their weight class” in the popular media.

And the list goes on: a Washington Post commentary on Shoofly pie, a painting of a Mennonite minister by Rembrandt; an appearance in Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest; Joseph Heller’s Catch-22; Harrison Ford hiding out among the Amish in Witness, cameos in The Office, The Simpsons, Modern Family; and entire shows Breaking Amish and Amish Mafia. I’m sure Mormons and Catholics get their share of attention, but they’re a lot bigger. According to Steven Carpenter, author of the fascinating new book Mennonites and Media, “punch above their weight class” in the popular media.

Several consistent themes have emerged over the centuries. The first: the Mennonite as a sober, self-sacrificing servant.

- Candide (1759): In Candide (1759), Voltaire’s cutting satire of Western civilization, a Mennonite emerges as one of the book’s few sympathetic characters. In Chapter 3 (“How Candide Escaped from the Bulgarian and What Became of Him”), we meet “an honest Anabaptist named Jacques.” This kindly soul helps Candide, who is being persecuted by religious zealots angry because Candide doesn’t believe that the Pope in the anti-Christ. Jacques by contrast, “took him home, cleaned him up, gave him bread, gave him money, and even offered him work.” Later Voltaire, who calls Jacques “charitable” and “virtuous,” describes a scene in which he tries to help the crew of a ship on which he is being held prisoner. In response, a sailor-guard violently strikes Jacques. This forces the sailor off-balance, and he falls overboard, clinging only to a broken mast. But Jacques rescues his persecutor, only to fall overboard himself. The sailor allows him to drown “without condescending even to look at him.”

- Life magazine (1946): In the May 6, 1946, issue of the magazine, perhaps the most popular of the era, they published an expose entitled “Bedlam, 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals Are a Shame and a Disgrace.” Sixteen pages long and evocatively illustrated, the article was in part the result of Mennonite activism. Thousands of Mennonite conscientious objectors worked in mental facilities during World War II, wanting to contribute to society without violating their convictions against killing human beings. The atrocities inflicted on patients shocked these pacifist orderlies, and they advocated for reform to the media. Soon after, Congress passed the National Mental Health Act. Mennonites also opened their own mental hospitals in California, Kansas, and Maryland.

In my next post I’ll describe some less-flattering representations of Mennonites in popular culture.