Last week, I excerpted some highlights from a recent intra-evangelical debate about Adam’s historicity in the (online) pages of Book & Culture. Today, some commentary.

I agree with William VanDoodewaard that the somewhat lopsided nature of the debate is itself remarkable: “Combined as participants we present one quarter committed to the historical Adam of historic Christian orthodoxy, yet the reality is that the only predecessors to our three quarters who abandon this Adam are found in Enlightenment skeptics, 19th-century higher critics, and 20th-century theological modernists or liberals. It is a small society on the fringe of Christianity in its most broad definition—one which I see with sadness heading outside the parameters of millennia of mainstream Christian confession, away from the Word of God.”

VanDoodewaard is correct that it’s remarkable that the roundtable featured only two participants committed to “the historical Adam.” And, yes, the arguments of others partly reflect from the “Enlightenment skeptics, 19th-century higher critics, and 20th-century theological modernists or liberals.” And most evangelicals, to be sure, have no interest in following their own theologians down such paths.

Peter Enns writes that “negative voices come from a small minority, largely from those who feel that commitment to theological structures that require a first human, Adam, cannot be compromised without the entire Christian tradition crumbling right along with it.” What Enns describes as a “small minority” VanDoodewaard identifies as a vast majority.

What explains this point of disagreement? First, even though biblical scholarship has in some ways moved on to new methodologies, far more evangelical theologians today are comfortable with the fruits of historical-critical scholarship and do not see it as posing a threat to Christian faith. At the same time, “ordinary” evangelicals are largely not conversant with such matters. Moreover, evangelical ministers and popular writers are not as engaged in the “Battle for the Bible” as was the case several decades ago. Although more recent conflicts, such as those over both marriage and gender roles, relate to matters of biblical authority, those conflicts have to some extent sidelined older conflicts over biblical criticism. Thus, whereas most evangelicals accept a fairly literal interpretation of Genesis 1-3 (though one should mention that it is not easy to accept literal interpretations of Genesis 1-2:3 and Genesis 2:4-25 simultaneously), many evangelical theologians have questioned those interpretations. I suspect VanDoodewaard is more accurate about the question of how most evangelicals would approach this debate.

Though I disagree with Enns’s assertion that Adam is “a minor character in the Bible,” I am very sympathetic to his view (and that of many others in the forum) that because evolution is “well established and utterly uncontroversial” among scientists, it is unwise for evangelicals to hitch themselves to a view of human origins in conflict with human evolution. Enns identifies “obscurantist apologetics” as a factor in the alienation of individuals from Christian churches. That may or may not be a primary factor. Indeed, both perspectives on the historicity of Adam and Eve — or on the subject of evolution — probably alienate different segments of young Americans and young Christians. Perhaps strident opposition to evolution would play poorly among millennials, but open questioning of traditional interpretations of Genesis 1-3 would probably play poorly as well.

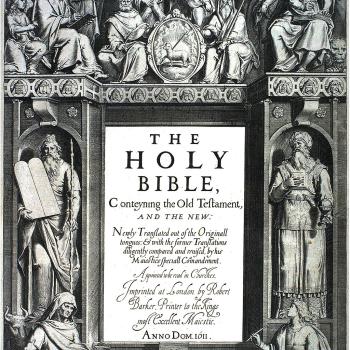

I have been reading Grant Wacker’s America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation. In his first chapter, Wacker discusses several components of Graham’s “theological core.” Among those is Graham’s faith in the Bible. For Graham, the Bible was a matter of faith. Wacker briefly narrates Graham’s encounter with biblical criticism through his friend and associate Charles Templeton. In the summer of 1949, Templeton was encouraging Graham to more fully grapple with matters of biblical authority through seminary education. Instead, Graham prayed about the matter while at southern California’s Forest Home retreat center. Graham emerged from the woods with his faith in the Bible restored. Many evangelicals are familiar with Templeton’s own “descent” into agnosticism and atheism, a warning that questioning the Bible leads to the collapse of faith.

Forest Home was not the end of the story for Graham, however. As Wacker explains, Graham’s “legendary encounter” with Templeton “ironically freed him [Graham] from the shackles of inerrancy and literalism. He embraced a faith-based foundation that trumped any sort of empirical or logical demonstration of the Bible’s factual accuracy — or inaccuracy, for that matter.” Thus, Graham in later years could tell David Frost that the Bible was not a “scientific book” and could inform Jon Meacham that he was “not a literalist in the sense that every jot and tittle is from the Lord.” In other words, especially as the years passed, when it came to the Bible Graham combined faith with flexibility.

In the Books & Culture roundtable on Adam, Hans Madueme very pertinently asks: “If scientific plausibility should guide the expectations we bring to Scripture, then why would we be Christians? Why would we believe that the Son of God became a man? That he died and rose again after three days? That he ascended into heaven? These fundamental Christian beliefs contradict everything we know from mainstream science. If we can no longer believe Adam was historical, then why should we believe in the resurrection?” As Madueme notes, Enns has addressed this question elsewhere, arguing that the resurrection occurred as a “present-day event”(more or less) for New Testament writers. It was not part of a mythical primordial history.

I don’t propose any simple answers to complex matters of biblical authority and scholarship. It occurs to me, though, that Billy Graham is not a bad model for how evangelical pastors might gracefully respond to issues of science and biblical scholarship as they emerge.