‘Tis the year’s midnight, and ’tis the day’s, and a good time to think of lost worlds and ghosts – in this case, the phantoms of bygone faiths. I offer a strange story, which raises some intriguing questions about the possible limits of popular memory in a non-literate society. And although this concerns ancient Britain, the implications extend to other faiths and their claims to preserve early traditions.

Recently, it has been startling to read revolutionary theories of how the great monument of Stonehenge was erected. We have long known that some of the stones, namely the bluestones, came from far west of the site’s present location, namely from west Wales. Just why the builders should have gone through the agony of hefting the stones 150 miles – presumably by water – has never been clear.

This image is in the public domain.

This image is in the public domain.

Now, though, we have a possible explanation. There was apparently a gap of some centuries between the time when the stones were quarried, around 3,400 BC, and when they reached Wiltshire to form the basis of historic Stonehenge, around 2,900 BC. The archaeologists involved offer an explanation for this, namely that the stones originally stood as a stone circle in West Wales, in Pembrokeshire. They were then moved as a unit to southern England, possibly because they were of such unusual sanctity. Alternatively, perhaps a tribe of people moved and migrated, and they decided to bring their sacred remains with them. Or else, Tribe A defeated and conquered Tribe B, and annexed their sacred site as a war trophy.

Directional correspondences likely played some role. The astronomical orientations of the Wiltshire Stonehenge we know suggest an obsession with Midwinter, the Winter Solstice, and the realms of the dead, and these concerns were presumably reflected in processions, pilgrimages and dances. In many societies, death and decline are obviously enough associated with the west, and with “Going West.” If you wanted to build a mighty shrine to the dead and the forces of midwinter, how better to do so than to take something already in existence at the farthest western reaches of the island of Britain, namely Pembrokeshire and west Wales?

Really, today, who can say? The point, though, is that the core of Stonehenge is a “secondhand monument”. That is not the only recorded example of such a move of European megalithic remains to a new site during antiquity. I say right away that this theory has been challenged, and others offer different explanations of how and when the bluestones moved, but that “older circle” theory has achieved serious respect.

Other, separate, research suggests that the full Stonehenge site would have had a strong healing function, and people traveled there from far afield in Europe, presumably to seek cures. Some speak of a “Neolithic Lourdes.”

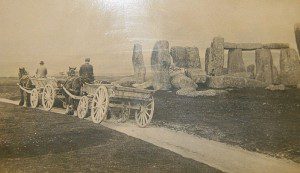

(Photo credit: Peter Trimming, under Creative Commons license).

(Photo credit: Peter Trimming, under Creative Commons license).

Who would have suspected such a picture? With great embarrassment, then, we turn to one of the most wholly bogus and discredited literary sources of the Middle Ages, the History of the Kings of Britain (c.1150) by Geoffrey of Monmouth. Although the work is highly influential, not least as the source for most of what we think we know about King Arthur, Geoffrey’s contemporaries recognized he was making most of it up.

Just how bad was Geoffrey’s reputation as a reliable historian? Some decades after his death, another Welsh author told a story about a man possessed by demons. “If the evil spirits oppressed him too much, the Gospel of St John was placed on his bosom, when, like birds, they immediately vanished; but when the book was removed, and the History of the Britons … was substituted in its place, they instantly reappeared in greater numbers, and remained a longer time than usual on his body and on the book.”

Geoffrey tells us about Stonehenge, and his story is flagrantly fictitious. According to him, the site was erected to commemorate a massacre around 450 AD (some 3,500 years later than the actual event), and the work was achieved by the magician Merlin.

This image is in the public domain.

This image is in the public domain.

What he also tells us, though, is that the Stonehenge that we now see in Wiltshire originally stood far to the west, and that it was relocated as a secondhand monument – dare I say, pre-owned? In both specifics, his statements appear to have been dead right.

In his Book VIII, Geoffrey tells us Merlin’s words to King Aurelius (excuse the archaic translation):

‘If thou be fain to grace the burial-place of these men with a work that shall endure for ever, send for the Dance of the Giants that is in Killaraus, a mountain in Ireland. [Chorea Gigantum, quae est in Killarao monte Hiberniae]. For a structure of stones is there that none of this age could raise save his wit were strong enough to carry his art. For the stones be big, nor is there stone anywhere of more virtue, and, so they be set up round this plot in a circle, even as they be now there set up, here shall they stand for ever.’

At these words of Merlin, Aurelius burst out laughing, and quoth he: ‘But how may this be, that stones of such bigness and in a country so far away may be brought hither, as if Britain were lacking in stones enow for the job?’ Whereunto Merlin made answer: ‘Laugh not so lightly, King, for not lightly are these words spoken. For in these stones is a mystery, and a healing virtue against many ailments. [Mystici sunt lapides et ad diversa medicamenta salubres.] Giants of old did carry them from the furthest ends of Africa [ex ultimis finibus Affricae] and did set them up in Ireland what time they did inhabit therein. And unto this end they did it, that they might make them baths therein whensoever they ailed of any malady, for they did wash the stones and pour forth the water into the baths, whereby they that were sick were made whole. Moreover, they did mix confections of herbs with the water, whereby they that were wounded had healing, for not a stone is there that lacketh in virtue of leechcraft’ [Non est ibi lapis qui medicamento careat].

When the Britons heard these things, they bethought them that it were well to send for the stones, and to harry the Irish folk by force of arms if they should be minded to withhold them.

And so it was done, amidst great celebration and religious ritual:

And when he had settled these and other matters in his realm, he bade Merlin set up the stones that he had brought from Ireland around the burial-place. Merlin accordingly obeyed his ordinance, and set them up about the compass of the burial-ground in such wise as they had stood upon Mount Killaraus in Ireland, and proved yet once again how skill surpasseth strength.

We have no idea what Geoffrey meant by his Mount Killaraus.

Never, please, ever accuse me of giving credence to Geoffrey of Monmouth on anything. The whole story might be a lucky guess by a great story-teller and historical novelist, which is what he was. The healing element is no great stretch, as people in Geoffrey’s own time often used ancient sites for such purposes. Also, Geoffrey is wrong on so much. The stones came from west Wales, not Ireland, and he describes Merlin transporting the whole monument, not just the bluestones.

But the idea of that relocation, that second hand quality, does take me aback. Is it possible that local folklore in early medieval times remembered a story that was then reported by some writer, which Geoffrey is transmitting? And that the story just included a statement as simple as “Those healing stones were not originally from these parts. Once, long ago, they stood just as you see them now, but in the far west”? Might it even have included some kind of name of a place or region, that survives as Killaraus?

It is tempting, but the timescale is daunting. We are after all talking about a move around 3,000 BC. The people who used Stonehenge itself might have had a long institutional memory, but the site was well past its heyday by 1300 BC or so. Greek writers like Hecataeus seem to describe the place as a still-flourishing entity c. 300 BC (and even that is controversial). Even so, the vast time frame that separates this from Geoffrey seems impossible.

This image is in the public domain.

This image is in the public domain.

Normally, I am very skeptical when ancient or medieval authors claim to pass on older traditions, because they so clearly demonstrate how rapidly accurate information fades away. In eighth century England, the author who wrote the poem The Ruin describes the country’s ruined Roman cities in such a way that shows he has not a clue about their actual operation or function. That is over a gap of just four hundred years – and yes, these cities are likewise attributed to “giants of old.” The Biblical account of the conquest of Canaan several centuries previously describes the destruction of the city of Ai, a name that means simply “heap of ruins.” That was, likely, all the memory that had survived of the site and its fate, and a story was invented accordingly. Claims that accurate tradition can survive more than a century or two without written continuity need to be examined very carefully.

So Geoffrey’s Stonehenge story might have been a lucky guess. It’s also certain that his contemporaries had some working sense of geology and building stones, and might well have recognized that some of the Stonehenge stones were not local. This was after all a huge age for building great churches and cathedrals, and people would have to have some knowledge of where good materials were to be found.

That might account for Geoffrey getting the geographic origin of the stones right. But he also wrote about Stonehenge being a second-hand monument, and he was (oddly) right about that too. Leave me, however briefly, with my illusions about oral tradition extending across several millennia.

Leave me with my ghosts.