I have been discussing the Islamic Hadith, and the apocalyptic traditions found in the section on “Turmoil and Portents” in the collection Sahih Muslim, “Pertaining To Turmoil And Portents Of The Last Hour” (Kitab Al-Fitan Wa Ashrat As-Sa’Ah). Specifically, I have suggested that many of these ideas stem from Christian sources, from the late seventh and eighth centuries, and that Christian converts might have imported them into the new faith.

Here, I will look at some of the most quoted anti-Jewish texts in the Islamic tradition. Beyond argument, Islam has a virulent tradition of anti-Semitism, although historically, it has been less lethal and systematic than that of the Christian world. The picture is very mixed. On plenty of occasions, Jews fled Christian persecution to seek protection from generous Muslim rulers, especially the Ottomans. On the other hand, while Western thinkers sometimes romanticize medieval Islam, Muslim-ruled Spain was the scene of savage pogroms against Jews, such as the Granada massacres of 1066. In modern times, anti-Jewish theorizing and propaganda have become very widespread and even mainstream in the Islamic world, commonly drawing on a standard body of texts. Even the ritual murder myth is widely credited in Islamic nations.

Often, these doctrines are supported by Qur’anic passages, but usually by twisting the original words to something quite beyond their original intent. I will not go into this argument in detail here, as I discuss in at length in my 2011 book Laying Down the Sword. None of the instances where the Qur’an is today cited for anti-Semitism refer to Jews as such, or else they address specific groups of Jews in a given historical context.

In that book, I discuss for instance the notorious passage in the Qur’an’s Sura 2, in which God recalls transforming sinners into despicable apes. Those who denounce the Qur’an as deeply anti-Semitic usually describe the evildoers as Jews, and many Muslims through the centuries have accepted that interpretation. But the text just does not support it. Although the story comes in a passage describing Moses and the children of Israel, the victims suffer for the sin of Sabbath-breaking. God proclaims, “Ye know of those of you who broke the Sabbath, how We said unto them: Be ye apes, despised and hated!” For this, they are made “an example to their own and to succeeding generations, and an admonition to the God-fearing.” They are punished for sin, not for Judaism. In fact, they suffer for a sin that centuries of rabbinic tradition categorized as grievous.

The anti-Semitic understanding stems from one tradition in the body of later commentaries, the Tafsir, which has entered folklore. The same comment applies to other instances where somebody is transformed into “apes and pigs,” as in Qur’an 5.60, where the victims are idol worshipers. In other cases too, later Qur’anic commentators have used texts to attack Jews, to present them as a condemned race, destined for hell. But in so doing, they are going far beyond the natural sense of the text.

The same defense cannot be offered of one of the ugliest Islamic passages on Jews, which stems from the Hadith. It is found in multiple versions, several of which come from the Turmoil and Portents:

Abu Huraira reported Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) as saying: The last hour would not come unless the Muslims will fight against the Jews and the Muslims would kill them until the Jews would hide themselves behind a stone or a tree and a stone or a tree would say: Muslim, or the servant of Allah, there is a Jew behind me; come and kill him; but the tree Gharqad [Boxthorn] would not say, for it is the tree of the Jews.

This is a warrant for anti-Jewish violence and struggle, and as such, the text is quoted in the Charter of Hamas.

But where do we find the origins of the ideas expressed here? As I suggested, this is a major departure from the world of the Qur’an and of Muhammad’s era. Nor does it fit regularly into the history of early Islam, when many Jews welcomed the Muslim conquerors as liberators from Christian rule.

The closest parallels to the text are actually in Eastern Christian writings, either Greek or Syriac, and they abounded during the eighth century, at the time when (I have suggested) the Turmoil and Portents originated. From the fourth century onward, Eastern Christians were frequently in conflict with Jews, and a couple of incidents in particular were deeply resented. In 614, for instance, Jews took advantage of the Persian conquest of Jerusalem to massacre many local Christians. After the Muslim conquest, Jews often persuaded Muslim authorities to suppress public symbols and displays of Christianity, notably the display of the cross. In the 720s, the Byzantine Emperor Leo III tried to force all Jews within his realm to receive baptism.

Anti-Jewish themes were prominent in Eastern Christian apocalyptic literature, which at so many points resembles the thought-world of the Turmoil and Portents. To take one example at random from a great many, the ninth century Apocalypse of Daniel described the rise of the Antichrist, who is strongly associated with the Jews:

And then the unclean spirits and the demons will go forth like the sand of the sea, those in the abyss and those in the crags and ravines. And they will adhere to the Antichrist and they also will be tempting the Christians and killing the babies of the women. And they themselves will suckle from them. … And then all flesh of the Romans will lament. And while there will be temporary joy and exultation of the Jews, (there will be) affliction and oppression of the Romans from every necessity of the evil demons. … And then the Antichrist will lift up a stone in his hands and say, “Believe in me and I will make these stones (into) bread.” And then (the) Jews will worship (him), who are saying, “You are Christ for whom we pray and on account of you the Christian race has grieved us greatly.” And then the Antichrist will boast, saying to the Jews. “Do not be grieved thus. A little (while and) the Christian race will see and will realize who I am.” And the Antichrist lifts up (his) voice toward the flinty rock, saying, “Become bread before the Jews.” And disobeying him, the rock becomes a dragon. And the dragon says to the Antichrist. “O you who are full of every iniquity and injustice, why do you do things which you are not able?” And the dragon shames him before the Jews.

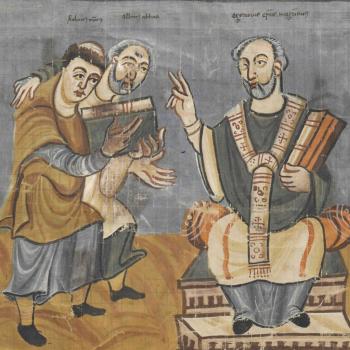

I suggest that these strong anti-Jewish themes originated among converted Christians, possibly clergy or monks, and probably during the eighth century.

In doing this, I am not trying to minimize the toxic quality of these passages, or to underestimate their pernicious influence on extremist Islamic thought. Rather, I want to trace their origins, and to stress yet again the commonalities of Islamic and Christian apocalyptic thought.