I’m pleased to present a guest post from Fletcher Warren, a recent graduate of Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota. Read this fine essay, but more importantly, check out the impressive digital history project, created by Warren and Chris Gehrz on which it is based. –David

***

Bethel at War is a locally-rooted history of a single institution. Written by a current professor and an alumnus, the project is an extended analysis of how the lives of people associated with Bethel were shaped the past century’s wars. With this in mind, why should scholars unconnected with Bethel be interested in delving into Bethel at War? Despite its narrow topical scope, several aspects of the project intersect larger areas of research including the histories of Christianity, higher education, and the impact of war on society.

In this post, I would like to focus on one particular connection to broader research, namely the historiography of student opposition to the Vietnam War. As an in-depth longitudinal study of a Christian liberal arts college, Bethel at War is poised to complicate the existing scholarly narrative of student anti-war activism. Kenneth Heineman notes in Campus Wars thatmuch of the literature on the college anti-war movement has focused on elite institutions — Harvard, Berkeley, Michigan, and the like. The literature has characterized these schools as activist and belligerent, the stalwarts of the student anti-war movement; their experiences have largely come to dominate popular memory of student response and have done much to foster the notion that students overwhelmingly opposed the war. More recently, other scholars have sought to decenter this trend by investigating non-elite schools. Yet these studies have roundly ignored the experience of sectarian institutions, to say nothing of distinctly evangelical colleges like Bethel.

Taylor historian William Ringenberg briefly addressed this subject in his 1984 classic The Christian College. Ringenberg characterized the Christian colleges as remaining “comparatively calm,” with students whose “views on the war did not significantly differ from the Vietnam policies of the Johnson and Nixon administrations.”¹ Ringenberg’s assessment was shared by Bethel president during the war, Carl Lundquist. Writing in the summer of 1970 after the Kent State shootings, Lundquist summarized conditions at Bethel:

“To my knowledge, very few small schools were scenes of turmoil such as characterized large university centers and no evangelical Christian school experienced this at all.”²

However, a close examination of Bethel student actions during the war reveals a campus embroiled in far greater upheaval than Lundquist admitted. Indeed, the evidence suggests that Lundquist’s assertion was simply wrong.

In the spring of 1969, student unrest at Bethel began to bubble up. Student marched to the University of Minnesota where they participated in a sit-in protesting University officials’ treatment of several American-American students. That October, several hundred Bethel students organized Moratorium day activities, including a program of teach-ins that cancelled three periods of classes. A full ten percent of the school signed an anti-war statement denouncing the war. A second Moratorium followed in November.

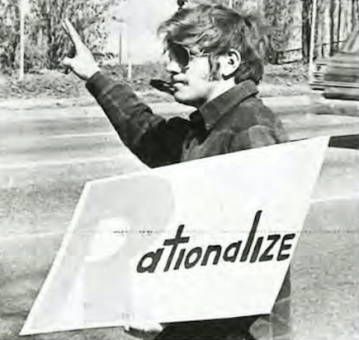

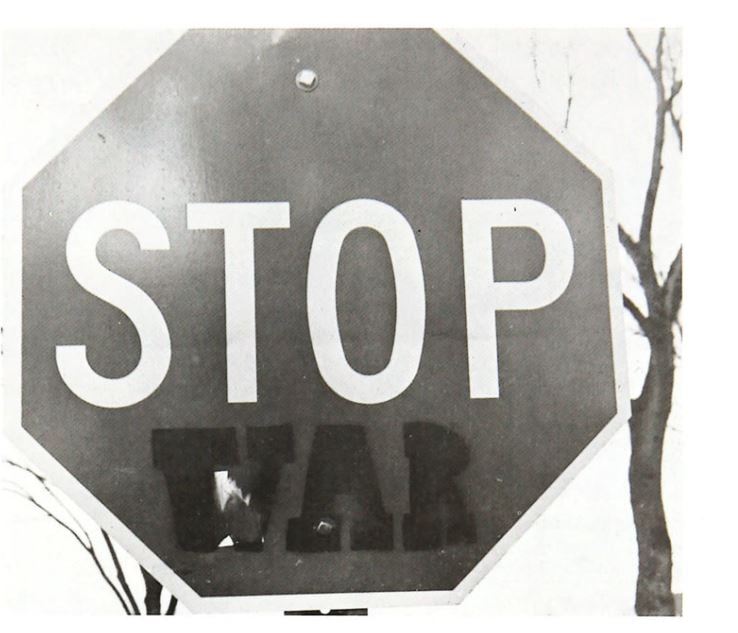

But those events paled in intensity to the reaction following Nixon’s Cambodian incursion in May of 1970. As National Guard troops shot and killed students at Kent State, Bethel student picketed a major thoroughfare with anti-war signs. A professor and several students marched off the picket line and onto campus, brandishing fake machine guns. To the dismay of other professors, the group began “non-invading invading” classrooms in a critique of Nixon’s attempted equivocation on the Cambodian campaign. Other vandalised area stop signs, stenciling the word “war” beneath the lettering.

In the semester following Lundquist’s declaration that Bethel was free of disturbances, a Dean was forced to intervene when a faculty member nearly assaulted Marine recruiters on campus. The college’s creative writing paper, the Coeval, published a poem by student Marjorie Rusche which gave voice to the alienation youth on campus felt:

“… Listen to the screaming of my brothers and sisters / skulls cracked up by billyclubs / brains blown apart in Vietnam foxholes / senses numbed with terror / while the orchestra plays Vienna waltzes.”³

Even before these activities, a 1968 poll was highly suggestive of campus feeling on the war. Administered as part of that year’s pre-twenty-sixth amendment student mock presidential election, the poll revealed that sixty-five percent of Bethel’s students advocated for withdrawal from Vietnam. In the same period, nationwide polling showed only fifteen percent of Americans thought the United States should withdraw.⁴ Bethel’s anti-war sentiment is particularly striking given that across the country, “very consistently […] younger respondents (those under thirty-five) [were] less supportive of withdrawal than older people.”⁵

If this poll can be trusted (and there is some evidence that complicates the picture), it suggests that Bethel students were significantly more against the war than the majority of Americans in the same period. In light of this evidence, how are we to understand Lundquist’s notion that Bethel was quietist? Can Lundquist (or Ringenberg, for that matter, who also lived through the events he analysed), truly stand apart from the events they experienced?

I’m not convinced they can. Lundquist clearly believed that his own campus was bucolic compared to other institutions. Yet his foil for judging Bethel’s unrest was equally clearly the elite universities like Berkeley and Columbia. There is no question that Bethel was peaceful compared to these schools, but at the same time Lundquist and Ringenberg both seem unaware of just how deeply quietistic many, if not most, non-elite secular institutions were during the war. This unawareness may be partially explained by expectations born of their evangelical faith; both men also argued that the peace on Christian campuses may have been due to their students “possess[ing] more of God’s grace and Dad’s discipline” than their secular counterparts.

A recent incisive case study of one such non-elite secular school, Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, demonstrates just how passive such institutions could be. Writing of Ball State’s 1969 Moratorium event, Anthony Edmonds and Joel Shrock note that only two hundred students turned out. In contrast, 144 Bethel students signed an anti-war petition on Moratorium day and over 200 students were involved in simply planning May 1970 protests. With Ball State’s student body approaching sixteen thousand and Bethel’s hovering in the mid two thousands, one school’s students were clearly more energized than the other’s.⁶

Beyond the issue of comparative unrest, one cannot diminish the role of Lundquist’s audience. His 1970 declaration of peace at Bethel was written to Bethel’s denominational sponsor — a constituency that trended more conservative than the school and contributed a significant portion of Bethel’s operating and long-term capital funds.

While Bethel at War only briefly touches on the experiences of other major Christian colleges at certain points, I know enough to suspect that student anti-war activity and sentiment at, for example, Calvin and Wheaton were similar to Bethel. What Bethel at War gestures toward, then, is the notion that these institutions should be considered collectively and seriously investigated for how they complicate a picture of, on the one hand, elite bastions of activism, and on the other, non-elite oases of quietism. Despite sharing much the same demographic background with students at Ball State — white, rural, Protestant, conservative and anti-communist — students at Bethel College displayed an unexpected level of anti-war activism. At Bethel at least, the evidence seriously challenges a narrative of evangelical quietude and raises a number of questions: What resources did evangelical faith contain to motivate and shape anti-war action? What does this suggest about the strength of the evangelical left on the Christian campus? How does such activism add new dimensions to our understanding of the rightward drive of evangelicals in the decades after the war? Bethel at War explores at length exactly these types of questions.

Fletcher Warren is an independent historian and legal researcher specializing in immigration issues. He graduated from Bethel University, where he wrote a senior thesis entitled, “‘A Long Way from Minneapolis’: Minnesotans in the Spanish Civil War.” He maintains an active scholarly agenda, focusing on political radicalism in the 1930s-40s and evangelical religious movements in the late 20th century. Fletcher plans to continue studying history at the graduate level.

References

¹ William Ringenberg, The Christian College: A History of Protestant Higher Education in America 2nd Edition (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 197; William Ringenberg, “Why Did Christian Colleges Remain Calm?” Taylor University Magazine, Fall 1974.

² Carl Lundquist, “Report of the Board of Education,” In 1970 Annual Report of the Baptist General Conference (Chicago: Harvest Press, 1970), 120.

³ Marjorie Rusche, “The Revolution,” The Coeval 1970-10

⁴ William Lunch and James Sperlich, “American Public Opinion and the War in Vietnam,” The Western Political Science Quarterly 32 (1979): 25.

⁵ Ibid., 32.

⁶ Anthony O Edmonds and Joel Shrock, “Fighting the War in the Heart of the Country: Anti-War Protest at Ball State University,” In The Vietnam War on Campus: Other Voices, More Distant Drums edited by Marc Jason Gilbert (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001), 146.