Ted Cruz marshals a rhetoric of Christian America in his campaign for president. Christians should “take back” or “reclaim” America, he says, from secularist liberals who have led the nation from its Christian origins. This vocabulary echoes that of his discredited adviser David Barton. His own father Rafael Cruz preaches a dominionist theology and suggests that his son’s campaign is a fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Glenn Beck declares that Cruz has been “anointed by God.”

These days it is political conservatives who most egregiously tie faith to their politics. But that hasn’t always been the case. Abolitionists seeking freedom for slaves proclaimed a Christian America. So did the American Bible Society. John Fea, author of a new book on the ABS, recently wrote, “It is hard to separate the religious work of the ABS from its mission to strengthen the Christian identity of the United States.”

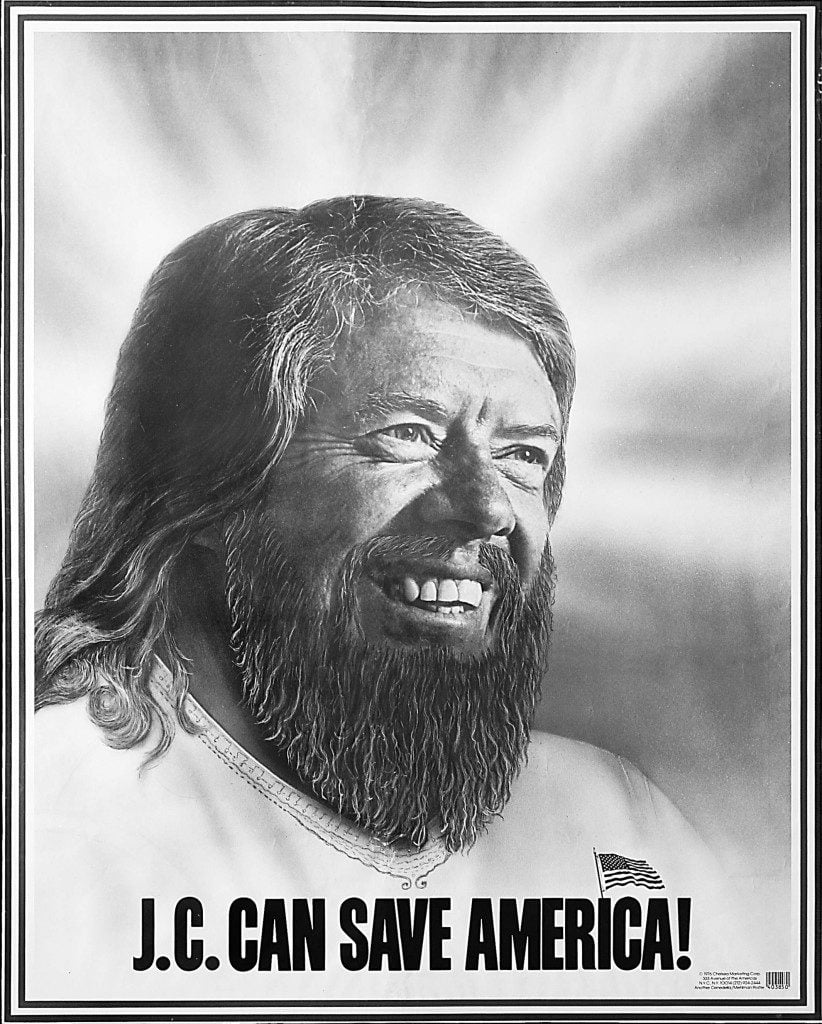

And then there was Jimmy Carter. Before Ted Cruz and George W. Bush, evangelicals used identity politics to mobilize for a Democratic candidate. Bailey Smith, president of the Southern Baptist Convention in the 1970s, told a crowd of 15,000 that the nation needs “a born-again man in the White House . . . and his initials are the same as our Lord’s.” Supporters mass-produced posters and pins that read “J.C.,” “J.C. Will Save America,” “J.C. Can Save America,” and “Born Again Christian for Jimmy Carter.” One poster depicted Carter with long, flowing hair and dressed in biblical garb with the caption “J.C. Can Save America.”

Some of the hagiographical material surrounding Carter’s candidacy portrayed God and politician working in concert. “There is a sense of history in the making; a feeling that something mysterious and irresistible is at work behind the scenes,” wrote Bob Slosser in a book called The Miracle of Jimmy Carter (1973). God had engineered conditions “which seem to have worked together to bring [Carter] to this moment in history.” In fact, Carter and God communed regularly. “Carter often—in the midst of a conference or conversation—closed his eyes, put his fist under his chin, bowed his head slightly, and talked to the Lord for a few seconds while the conversation continued around him.” Such spiritual integrity, Slosser explained, gave the candidate special resources which could be used to reshape the nation. Slosser surmised that the election “could bring a spiritual revival to the United States and its government.”

As far as I know, Carter did not engineer this rhetoric. In fact I imagine that he would have seen it as theologically problematic. But his overenthusiastic supporters nonetheless designed initials and a ambiguous body on campaign ephemera insinuating that Jimmy Carter was a political surrogate for Jesus Christ himself.

Whether coming from supporters of Carter or Cruz, this kind of intertwining of political and religious beliefs feeds a dualistic brand of politics that is breathtakingly arrogant and fuels ressentiment. It suggests that evangelicals are the sole hearers of God, that they alone can save the nation.

This is bad for politics, and it is bad for faith. In C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters, the senior devil tells the junior devil to inspire the mixing of partisan politics and religious beliefs in his human subject, who seeks to baptize his politics with Christian language, doctrine, and sentiment. It often makes politics or the nation an idol. It can make “the World an end and faith a means.” This, according to the devils, is a good way of corrupting faith.

It is also possible that the J.C. whose words Ted Cruz reads in the New Testament may not like the categorization. Perhaps it is not America that needs saving. In contrast to the theocratic Old Testament, J.C.’s kingdom extended far beyond a nation. At the same time, it was concerned with much smaller groups of disciples. Perhaps J.C. might not care so particularly for such a jingoistic preoccupation with America, for flags in religious sanctuaries, for electioneering at church. One of my favorite theological quotations–“Those who carry crosses work with the grain of the universe”–helpfully articulates a vision that is at once more particular than partisan and more grand than grandiose.