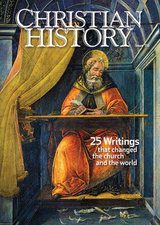

What are the most influential writings in Christian history?

Last fall the magazine Christian History tackled that question, surveying church historians to come up with a list of the top 25 Christian “writings that changed the church and the world.”

Last fall the magazine Christian History tackled that question, surveying church historians to come up with a list of the top 25 Christian “writings that changed the church and the world.”

I enjoy Christian History; in fact, I’m in the middle of writing a piece for it on Christian responses to Nazism. But I had some bones to pick with a list that named no women and no one from the Global South save two North Africans from late antiquity (Athanasius and Augustine). And someone who self-identifies as a Pietist isn’t likely to appreciate a list that’s heavy on theological treatises and light on other types of Christian writing.

(As I noted in my post featuring seven films on faith, “the chief virtue of doing a listing exercise like this is that it inspires readers to reach for new heights of indignant eloquence….”)

But what’s actually stuck with me most is that CH actually put together a list composed almost entirely of books, not writings.

Now, Christians are people of The Book. And like the scholars surveyed by CH, I’ve spent almost all of my life reading books, and a smaller, more recent chunk of my time writing them. But I also know that Christian thought, feeling, and imagination has been shaped and spread by other, equally powerful modes of writing. So I want to spend the next three weeks sharing how non-books have changed the church (if not the world), using my own experience as a jumping-off point.

* * * *

We’ll start with the one type of non-book writing that CH acknowledged. My Bethel Seminary colleague James D. Smith III was invited to assemble a list of “25 of Christianity’s greatest hymns.” (By the way, Philip has previously written about hymns as teaching tools, in this 2012 post.) Jim observes that

From the earliest times, Christians have associated “psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs” with teaching, personal disciplines (Col. 3:16), and confessing of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (Eph. 5:18-21).

His list spans eighteen centuries, from “Shepherd of Eager Youth” (Clement of Alexandria, ca. 200) to “In Christ Alone” (Keith Getty & Stuart Townend, 2001). One of six entries from the 20th century is Stuart Hine’s “How Great Thou Art,” whose tune (“O Store Gud”) was first popularized by an early leader in the Swedish wing of my own denomination, the Covenant Church.

Alas, there was no room for three of my favorite expressions of Swedish Pietist hymnody: Lina Sandell’s “Children of the Heavenly Father” and “Day by Day,” and “Thanks to God for My Redeemer” (whose original text was by a Swedish member of the Salvation Army, A.L. Storm, but whose English translation and tune came from Covenanters: Carl Backstrom and J.A. Hultman, respectively). While my spiritual ancestors defied Swedish law by gathering in small groups to study the Bible, they were singers as much as “readers” (läsare).

So why do these writings deserve our attention at least as much as books? How can hymns be as influential as theological treatises by the likes of Augustine, Aquinas, and Calvin?

Start by considering what Steven Guthrie writes about music and the arts in Zondervan’s Dictionary of Christian Spirituality:

Not only do the arts demonstrate the inadequacy of a wholly abstract faith; they also offer a means of bringing theological convictions to lived expression. If Christian spirituality is the domain of lived Christian experience, then clearly the arts are a valuable asset in the spiritual life. In song and dance, in sculpture and drama, inward convictions are drawn out into the realm of action and motion; into the lived world of time and mass and extension in space. Conversely, by enlisting sense and imagination the arts draw God’s truth in more deeply; embedding and incarnating belief at many levels of one’s person.

I’ll come back to the first idea (“bringing theological convictions to lived expression”) in a later post, when I go beyond writing altogether and tell the story of my tradition’s most (in)famous contribution to religious art. But I think the notion that hymns, like dance, drama, and visual art, can embed and incarnate belief is hugely important. Guthrie concludes this section with Richard Mouw observing “that the poetic imagery of a hymn text ‘impresses [a] theological point on your consciousness as no scholarly treatise can do.’ Through melody and verbal imagery the theological truth ‘becomes graphic.’” (Quotations from Mouw’s collaboration with Mark Noll, Wonderful Words of Life: Hymns in American Protestant History and Theology.)

No doubt the theology of any hymn reflects the near or distant influence of books. But in terms of where individual Christians actually get their beliefs about everything from the nature of God to the reality of sin to the power of grace… I suspect that hymns and worship songs play more of a role (not always for the better — see Susan Wise Bauer’s chapter in the Mouw/Noll collection) than longer, more sophisticated writings.

Or sermons, for that matter. As C.O. Rosenius, the leading figure in the Swedish revival whose great hymnwriter was Lina Sandell, wrote in 1850:

How often hasn’t it been the case that many precious lessons have been planted deep in our heart by songs, long after the sermons are forgotten! Luther’s enemies complained that he did more damage (to the pope’s church) through his songs, than through all his sermons.

Moreover, hymns speak to our hearts as much as our minds — and sustain the former when the latter gets tied up in knots trying to reconcile irreconcilable theological paradoxes.

Last year I wrote about singing “Children of the Heavenly Father” at a funeral. We were celebrating the life of a man not much older than me, a husband and father who left behind a wife and young family. And his own parents were there with us; he was the second adult child they had outlived. Here’s what came to my mind:

…between empathy for Murriel and Larry [the parents of the deceased] and anxiety for Lena and Isaiah [my own children], the final verse of the hymn caught in my throat:

Though he giveth or he taketh

God his children ne’er forsakethBut much as my mind itched to battle the problems of evil and suffering, to conquer doubt with theology and philosophy, I instead paid heed to the suggestion at the center of our pastor’s meditation: that one of the mercies of such a loss is that it reminds us that we are not God. Unable to fully understand, we are given an opportunity to relinquish our delusions of control and power and actually do what we’re supposed to have been doing all along: “Be still, and know that I am God!” (Ps 46:10)

So I paused and meditated, to the tune of “Children of the Heavenly Father,” on the psalm’s claim (made twice) that “The Lord of hosts is with us; / the God of Jacob is our refuge” (vv 7, 11).

Nestling bird nor star in heaven

Such a refuge e’er was given.The hard part is that we take refuge in a God of paradox: he provides and deprives, such that in death there is life and in sorrow, grace. (See also “Day by Day,” in which we pray to “He whose heart is kind beyond all measure,” a Provider who gives “pain and pleasure” and mingles “toil with peace and rest.”)

How, at a funeral, can we affirm that “From all evil things he spares them”?

There is no real intellectual resolution to that question. As Murriel’s fellow choir members sang on Sunday, “Endless Your grace, O endless Your grace, / Beyond all mortal dream.”

But for all the theological loose ends in a hymn like “Children of the Heavenly Father,” there is still resolution: a simple musical idea that somehow doesn’t collapse under the weight of doubt. There is refuge in the gentle loveliness of a folk tune that we learn as children and continue to sing, child-like, through the last of our years.

What Kathleen Norris once observed about the psalter may also describe the hymns that descend from my favorite writing in Scripture:

What Kathleen Norris once observed about the psalter may also describe the hymns that descend from my favorite writing in Scripture:

To your surprise, you find that the psalms do not deny your true feelings but allow you to reflect on them, right in front of God and everyone…. If the psalm doesn’t offer an answer, it allows us to dwell on the question.

In short, to read psalms and hymns is to pray, not to comprehend. (“He who sings,” thought Augustine, “prays twice.”)

One more point here… I love the solitude of reading a book, but hymns constitute that rarest form of modern Western writing: one that’s almost always read with other people. Singing “Children of the Heavenly Father” at that memorial service, I was wrestling with conflicted thoughts and feelings as part of a gathered, grieving community. “In the really hard times,” a Benedictine nun once told Norris, “when it’s all I can do to keep breathing, it’s still important for me to go to choir. I feel as if the others are keeping the faith for me, pulling me along.”

Similarly, the last time I can remember singing “Thanks to God for My Redeemer” was at our congregation’s Thanksgiving eve service last November. Because of speaking engagements at other churches, I hadn’t seen much of Salem that fall. So, I wrote at my blog the next day:

…it was almost startling to look at around at hundreds of other faces and be reminded of how many different people I know, and am known by, in our congregation.

Our tradition for this service is that the pastors don’t preach; instead, two laypeople are invited to share prepared meditations, then the mic is passed around to anyone else who wants to share a more spontaneous expression of gratitude. People I know well and barely at all shared what was on their hearts: loss, gain, sickness, healing, death, life.

So as we together sang “Tack O Gud” [the original Swedish name of the tune] I felt keenly aware of the fact that I was giving “thanks for joy and thanks for sorrow” not solely in my own behalf, but for others, with others.

Hymns, in other words, incarnate belief not just in my individual body, but in the collected, diverse Body of Christ. And they embed belief not just in a mind whose attention is focused on a book, but in the lived experience of a community that worships, grieves, rejoices, and prays together.

What do you think? How significant are hymns as Christian writings? Do you have a favorite hymn that exemplifies their impact on your life?