You may have noticed an interesting theological debate currently under way among evangelicals. Critiquing the New Testament evidence for the Virgin Birth, Atlanta megachurch pastor Andy Stanley ventured the opinion that “Christianity doesn’t hinge on the truth or even the stories around the birth of Jesus. It really hinges on the resurrection of Jesus.” This view attracted a rebuke from Albert Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, who declared that the Bible’s claims about birth and incarnation were “the central truth claim of Christmas.” The Bible, he says, “reveals Christ and it reveals Christ to have been conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of a virgin, born in Bethlehem as predicted by the prophets, and born in order to save sinners.”

This is a significant debate, and I hope it continues, but when people do pursue the argument, they should remember the very extensive arguments about this topic in the early church. Let’s not reinvent the wheel.

To take a specific issue, assume for the sake of argument that we reject the claims about Christ’s birth and incarnation, but that we do preach his divinity or Sonship. So if he was not divine from his birth, at what moment did he actually become divine? When did he become the Son of God? Was it at, or even after, the Resurrection, or was it at some point during his lifetime? Actually, early thinkers generally tended to one particular answer to this question, and it’s one that is quite relevant around this time of year.

In Western Christianity, Christmas falls on December 25, with the twelve days of that season culminating on January 6, Epiphany, which conventionally marks the visit of the Magi. The Christmas commemoration is obvious enough, but that January 6 date is interpreted differently in various parts of the world. Crucially, it is usually followed closely by the celebration of Christ’s Baptism, a linkage I will explain shortly. But at one time, that January date was a lot more significant than December 25.

The story takes us back to the very earliest days of Christian history, when some drew a sharp distinction between the man Jesus and the Heavenly Christ. During the second century, there were multiple competing interpretations of Christianity. To oversimplify, Gnostic Christians taught that Christ came from higher spiritual realms to redeem and enlighten the sparks of true divinity that survive within the pollutions of matter.

Egypt produced two of the earliest and most influential Gnostic teachers, Basilides and Valentinus. In the 120s, Basilides taught a complex system of Creation and unfolding degrees of reality. One supernatural figure, the Great Archon, wrongly believed himself to be the ultimate God, forgetting or ignoring the higher spiritual levels, and this is the divine figure we know from the Old Testament.

The true heavenly powers sent messengers to illumine and redeem the world, and also to teach the Archon his error. One of that exalted elite was the Aeon known as Christ, who descended on Jesus at his Baptism, and remained with him until the Crucifixion. The Christ of the Gospels thus taught absolute truth, but the material Jesus was only his vehicle.

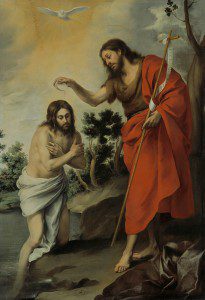

This image is in the public domain

Put another way, Jesus was not divine from birth, but rather divinity descended upon him at a specific moment, namely at his baptism in the Jordan. That fits reasonably with the interpretation we might get if we relied only on the gospels of Mark and John, where the baptism clearly marks some kind of explosive, transformative, moment in Jesus’s career. Neither Mark nor John tells a birth story, and Mark shows no awareness of the birth occurring in Bethlehem (John probably does). Of course, that reading of the Baptism is not the only possible interpretation, nor necessarily the best, but it does have an internal consistency.

As Irenaeus wrote around 180,

The father without birth and without name, … sent his own first-begotten Nous [Mind] (he it is who is called Christ) to bestow deliverance on them that believe in him, from the power of those who made the world. He appeared, then, on earth as a man, to the nations of these powers, and wrought miracles. ….

Those, then, who know these things have been freed from the principalities who formed the world; so that it is not incumbent on us to confess him who was crucified, but him who came in the form of a man, and was thought to be crucified, and was called Jesus, and was sent by the father, that by this dispensation he might destroy the works of the makers of the world.

Although Basilides’s formulation diverges so massively from any familiar Christian orthodoxy, he claimed to have received his teachings from Glaucias, an interpreter of St. Peter, and also claimed a special tradition from the apostle Matthias. In other words, he boasted an alternative apostolic succession.

So what does this have to do with Christmas or the Epiphany? Well, at the end of the second century, Clement of Alexandria tells us that Basilides’s followers had a special veneration for Jesus’s Baptism, which they celebrated on or near January 6:

And the followers of Basilides hold the day of his baptism as a festival, spending the night before in readings. And they say that it was the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar, the fifteenth day of the month Tubi; and some that it was the eleventh of the same month.

This is a fascinating text in lots of ways, including the early attestation of a Christian night service devoted to scripture reading (prodianuktereuontes en anagnosesi). And oh, how we would like to know what those readings actually were! The Gospel of John, perhaps?

The baptism marked the moment at which the spiritual being Christ descended on the man Jesus, to remain with him until the crucifixion. This was thus the date at which God became manifest – in Greek, the time of Epiphany. The mainstream church appropriated the festival easily enough, as the lines between orthodoxy and heresy were not too strictly defined in Egypt at this time. (Do note here that I am summarizing this briefly, and ignoring a great many scholarly caveats and complexities).

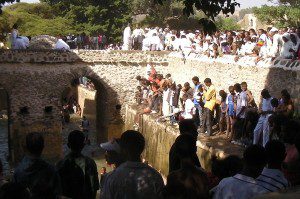

So is this all ancient history? Well, maybe not, as we see if we move from Egypt to the ancient and still flourishing church of Ethiopia. Still today, by far the greatest celebration of the year is Timkat, which marks the Baptism of Christ, and the Epiphany. The event draws pilgrims in their millions. But why? I suggest that the commemoration recalls that ancient time when Jesus’s followers had a special veneration for the Baptism, which some believed marked the moment when Christ received his divinity.

Although most of the church’s earliest records have been lost, we know that Ethiopian Christianity was flourishing by the fourth century, and that it has always had a very close relationship with the church of Egypt, and especially Alexandria. Not surprisingly, then, Ethiopia keeps alive very early Egyptian interests and obsessions, even some that might have been forgotten in Egypt itself. Whatever the church’s official theology says, Timkat recalls a very old interpretation of Christ’s baptism.

This image is in the public domain

Epiphany, then, means “made manifest,” but once upon a time that idea was not connected to the Magi, but to a quite separate event.

If you want to see Timkat at its most spectacular, then go and see the celebrations in Ethiopia’s royal city of Gondar. Gondar, by the way, was built in the seventeenth century by a great Ethiopian emperor who bore the auspicious name of Basilides.