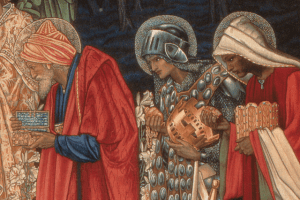

As any Bible reader knows, the infant Jesus was visited by Magi, who brought gold, frankincense, and myrrh, and a cold coming they had of it. But where did they actually get these gifts from? However arcane and speculative such a question may seem, the resulting curiosity generated a vast body of Christian literature. Although not mentioned in canonical scripture, the resulting tales became an integral part of faith for countless believers.

In the West, the Magi are usually numbered as three, hence the “Three Kings” of countless Christmas pageants. But this number has no scriptural warrant. The Western number is based on the assumption that each magus must have brought his own distinctive present, of which three are listed. Eastern churches think of twelve Magi, and the Irish envisage seven. Nor does the evangelist Matthew call them kings.

Matthew’s account left much to the imagination, permitting authors and pseudo-historians to speculate freely about the gifts and their origins. Yes, they were fascinated by the Magi, and debated furiously over their names and origins. But again, what about the gifts themselves?

This image is in the public domain

Ideally, they should be located firmly in the broader biblical story, and preferably given some world-historical significance. How better to do this than to link them to Adam, and to the original Paradise that had been lost through his sinful disobedience? In the early centuries of the Christian era, a large corpus of Jewish and Christian writings explored the world of Adam and his family, and the Cave of Treasures (Me`ârath Gazzê) was a central feature of these tales. Many of these works came from the Syriac-speaking East, and they found a welcoming home in the Ethiopian church. We call such works apocryphal, or pseudepigrapha, but such terms should not minimize their enormous influence over many centuries

In the wonderful tract called The Book of the Cave of Treasures, the objects date back to earliest times. After the expulsion from Eden,

Now Adam and Eve were virgins, and Adam wished to know Eve his wife. And Adam took from the skirts of the mountain of Paradise, gold, and myrrh, and frankincense, and he placed them in the cave, and he blessed the cave, and consecrated it that it might be the house of prayer for himself and his sons. And he called the cave the Cave of Treasures.

Yared, who died before the Flood, orders his son Enoch and his other heirs:

Let him that is among you who shall go forth from that holy country take with him the body of our father Adam, and the offerings [of gold, frankincense, and myrrh] that are in the Cave of Treasures, and let him carry away and deposit the body in the place wherein he shall be commanded by God to set it down.

In the Testament of Adam, Seth describes the death and burial of the first man. After Adam’s death, Seth places his last testament in the Cave of Treasures, “with the offerings Adam had taken out of Paradise, gold and myrrh and frankincense.”

Around 400 AD, the Six Books Apocryphon reports that

Our father Adam when dying, commanded in his Testament his son Seth and said to him, “My son Seth, lo, offerings are laid by me in the Cave of Treasures, gold and myrrh and frankincense; because God is about to come into the world, and to be seized by evil and wicked men, and to die, and make by his death a resurrection for all children of Adam.” And lo, the Magi, the sons of kings, came carrying these offerings, and went and conveyed them to the Son of God, who was born of the Virgin Mary in Bethlehem.

The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan ends with a description of the coming of Christ, and here, the Magi deliver the three gifts “that had been with Adam in the Cave of Treasures.”

Do I believe any of this as sober history? Of course not. But I thoroughly appreciate the impulse that drove these story-tellers. They were seeking to show that the story of Christ was not just something tacked on as an appendage to a larger Biblical story, but rather it was the main theme and point of that whole narrative. In a different form, this is what Paul was seeking to do with his particular references to Adam and the Fall.

The gifts of the Magi originally came from Paradise, and they were returned to the newborn King who promised to restore that Paradise. That is as logical as it is concise.

That idea runs through The Book of the Cave of Treasures. Adam is buried in a cross-shaped grave, and the site of his skull becomes Golgotha, where Christ would be crucified. The cross itself grows from a tree sprung from that grave:

And when the Wood [the cross] was fixed upon it, and Christ was smitten with the spear, and blood and water flowed down from His side, they ran down into the mouth of Adam, and they became a baptism to him, and he was baptized.

The image of Adam’s skull in that final sentence makes the theological lesson unforgettably clear. Adam’s Fall ruined a world that Christ saved. And the two figures must always be linked inextricably, and materially.