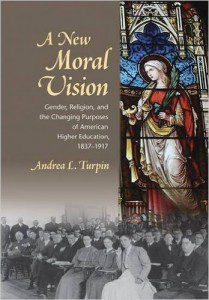

We’re delighted to welcome Andrea Turpin back to The Anxious Bench. A colleague of Beth and Philip’s at Baylor University, Andrea is the author of A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1837-1917. (On that book, see her January interview with Kristin.) We were curious what she made of last week’s controversy linking “school choice” with the tradition of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs)…

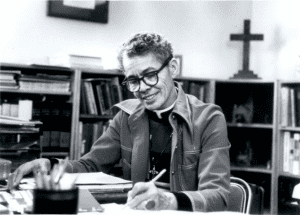

Pauli Murray, the first female African-American Episcopal priest in the United States, lacked school choice. Before pursuing ordination in 1977, Murray worked as a civil rights lawyer, but obtaining her credentials had proved vexing. When I told my students her story last semester, their jaws literally dropped. In 1933, Murray earned her undergraduate degree from a women’s college, Hunter, in New York. Five years later Murray applied for graduate work in her home state at the coeducational University of North Carolina, but was denied admittance because she was black. She therefore earned her law degree from Howard University, a coeducational HBCU, in 1944. Murray graduated first in her class. In order to qualify to return to Howard to teach law, she applied to Harvard Law School for additional training. Harvard, after all, could boast that W. E. B. DuBois had earned a PhD there. Harvard denied her admittance—not because she was black, but because she was a woman.

I thought of Murray’s story when I read about the recent controversy surrounding Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’s comments linking HBCUs to the concept of school choice. DeVos wrote, “HBCUs are real pioneers when it comes to school choice. They are living proof that when more options are provided to students, they are afforded greater access and greater quality. Their success has shown that more options help students flourish.” Widespread public outcry pointed out that HBCUs arose to meet the demands of African-American students who were systematically shut out of other institutions, not just to provide them with alternative options. As DeVos subsequently clarified, “Bucking that status quo, and providing an alternative option to students denied the right to attend a quality school is the legacy of HBCUs. But your history was born, not out of mere choice, but out of necessity, in the face of racism, and in the aftermath of the Civil War.”

Murray, for example, could not simply choose a women’s college or an HBCU because she thought those types of institutions better met her needs; they were at times the only institutions willing to serve her. The founders of colleges like Hunter and Howard had indeed made higher education available to Murray, but continuing gender and racial prejudice meant she did not have robust choice.

I am fascinated by the way Christian faith has motivated both parties in this recent controversy. The NAACP’s response to DeVos’s initial comments read, “Following the Civil War, church denominations, mission societies and philanthropists established HBCUs in order to educate formerly enslaved African Americans. By providing quality education to formerly enslaved African Americans, HBCUs resisted a racist education system that fought to restrict learning to wealthy families of European descent.” In other words, faith inspired many of the reformers who established HBCUs to educate former slaves shut out from existing institutions of Southern higher education. Meanwhile, faith motivates Secretary DeVos, a Calvin College graduate, in her campaign to institute a controversial school choice voucher system: she believes doing so would improve the education of American children, in part by making a specifically religious private school education affordable to more of them. Critics argue, however, that the program would drain funds from public schools that serve minority students.

So how should Christians think about educational policy? The history of Christian higher education provides food for reflection today. I suggest we consider the parallels between women’s higher education and African-American higher education that were all too real for Pauli Murray. The first US institution to grant a true BA degree to women—and perhaps the first in the world—was Oberlin College in Ohio, an evangelical institution that boasted famous revivalist Charles Finney as one of its early presidents. Founded in 1833, Oberlin admitted women to the BA program in 1837, and the first women took their bachelor’s degrees in 1841. Oberlin was not only the first coeducational college in the United States; it was also one of the few colleges to educate black and white students together. In other words, it educated women and men of both races during a time of great fear of racial intermarriage, or “miscegenation” as it was known. And that’s still not all: Oberlin also pioneered a sort of work-study program designed to make the college affordable to women and men who would otherwise find it financially prohibitive to obtain higher education.

I argue in my book that Oberlin’s founders created such an unparalleled institution out of a philosophy I call “evangelical pragmatism.” (No relation to the American philosophical movement.) Evangelical pragmatists were a subset of American evangelicals so committed to the advancement of the Christian message that they were willing to override contemporary race, class, and gender norms to get the job done. Specifically, they argued that women—and in the case of Oberlin, African-Americans—ought to receive an education of the same quality historically offered to white men so that more people would be maximally equipped to preach and teach the gospel thoughtfully and well. Evangelical pragmatists believed that all people could best serve God when they developed their talents as fully as possible. They thought God would then personally direct individuals into the lines of work that best advanced divine purposes.

I argue in my book that Oberlin’s founders created such an unparalleled institution out of a philosophy I call “evangelical pragmatism.” (No relation to the American philosophical movement.) Evangelical pragmatists were a subset of American evangelicals so committed to the advancement of the Christian message that they were willing to override contemporary race, class, and gender norms to get the job done. Specifically, they argued that women—and in the case of Oberlin, African-Americans—ought to receive an education of the same quality historically offered to white men so that more people would be maximally equipped to preach and teach the gospel thoughtfully and well. Evangelical pragmatists believed that all people could best serve God when they developed their talents as fully as possible. They thought God would then personally direct individuals into the lines of work that best advanced divine purposes.

At Oberlin, the coin of evangelical pragmatism had two sides. One was admitting students without regard to race, class, or sex. The leaders of Oberlin believed doing so would increase the number of people as prepared as possible to be useful to God—but also that the policy was simple justice. Oberlin’s founder John J. Shipherd asked the trustees to admit black students in part “…because it is right principle; and God will bless us in doing right” (quoted in A New Moral Vision, p. 68, emphasis original). The other side of the coin sought to provide all admitted students with even more biblical and theological training than was standard at American colleges at the time. In this manner, not only would an Oberlin education unfold more people’s nascent abilities, but it would also train them in the specifics of the Christian faith that Oberlin leaders believed essential to students’ own spiritual maturity and to their ability to evangelize others. Both sides of the coin served God: the first by developing the talents of all people God had created, and the second by providing them with a distinctly Christian education.

The contemporary school choice debate pits these goods against one another. As I have written before at The Anxious Bench, I am a firm believer in institutional pluralism at the collegiate level. It seems to me to be the best way to serve multiple constituencies well. In pre-collegiate education, however, a voucher system as currently designed would make specifically Christian education affordable to more students only by pulling money away from public schools, which remain either the best or the only option for many students across the country. To provide more students religious schooling, vouchers potentially lower the quality of education available to others.

The leaders of Oberlin would have been horrified if they had believed that their approach to training more people for Christ would have meant leaving other people fewer opportunities. Their vision of justice was more holistic than that. In order to help bring all of God’s creation to full flower, Christians today need to think not only of our own children, but also of the children of others. We should make sure that any educational policy we advocate both allows us to pass on the faith to the next generation and best facilitates the flourishing of all people God has created, regardless of race, class, gender—or religion.