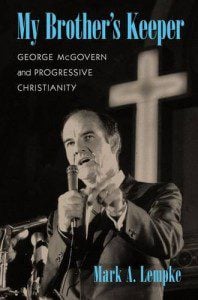

I’m pleased to post this interview with Mark Lempke, who just published the terrific book My Brother’s Keeper: George McGovern and Progressive Christianity with the University of Massachusetts Press. Mark teaches history in Singapore for the University of Buffalo. Part II, in which Mark explains why he’d want McGovern on his pub trivia team, will be published in two weeks. –David

***

David Swartz: Who was George McGovern?

Mark Lempke: In the most immediate sense, George McGovern was a Democratic U.S. senator from South Dakota, serving between 1963 and 1981. He is most well-known for his strong opposition to the Vietnam War, a stance that led him to challenge Richard Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. Historically, his loss made him something like a cautionary tale. If you are too liberal, you won’t win. Or if you choose the wrong running mate (as McGovern did with Tom Eagleton, who misled the campaign about his history of mental illness), you won’t win either. All of this may be true, but I wanted to consider George McGovern as a contributor to progressive Christianity in the 1960s and 1970s. His campaign was unusual in that it took the prophetic emphasis on social justice that was so characteristic of the civil rights and antiwar movement, and applied it to electoral politics.

D.S.: The McGovern family had close ties to the evangelical college Houghton. What led McGovern away from that tradition toward the mainline?

D.S.: The McGovern family had close ties to the evangelical college Houghton. What led McGovern away from that tradition toward the mainline?

M.L.: The Houghton connections were actually what first intrigued me about McGovern. I attended Houghton myself- Class of 2005- and when I was a student there, I did a research project on the 1972 election. I was surprised to learn that McGovern’s father, a Wesleyan pastor, was one of Houghton’s first generation of students. To answer your question, though, it was McGovern’s embrace of the social gospel as a college student that marked his departure from his family’s staunch evangelicalism.

At the time, the evangelicalism that McGovern would have encountered in his father’s church and at summer revivals was intensely focused on personal salvation and personal holiness, and had little understanding of the systemic and corporate nature of many social problems. Given the state of the world when he resumed his studies after service in World War II, he didn’t see such an intensely individualized faith as serving any real purpose. Through his reading of Walter Rauschenbusch and other social gospel thinkers, he began to see one’s faith could be channeled in service to the hungry, and the poor, and the sick. He even trained Garrett Theological Seminary for eighteen months, and spent most of that time as a student pastor in Diamond Lake, Illinois. To McGovern, any religious faith was virtuous only insofar as it could alleviate suffering in a hurting world.

D.S.: So what? McGovern lost in a landslide to Nixon in 1972.

Did he ever! But for better or worse, the coalition McGovern cobbled together transformed into the Democratic Party’s base in the years since. Feminism, Black Pride, Hispanic caucuses, leftist student groups…all of these forces wrested the nomination for McGovern in 1972 when a lot of Democratic Party insiders would have preferred Hubert Humphrey or Ed Muskie. McGovern was even the first candidate to have support from the gay community. On the other hand, he hemorrhaged support among blue-collar workers and so-called “ethnic whites”–the kind of people Jefferson Cowie wrote about. It fractured the New Deal coalition. McGovern used to joke, “I opened the doors of the Democratic Party and 10 million people ran out.” In 1972, all this meant that McGovern failed to clear even 40% of the popular vote. In more recent times, those demographics gave Democrats the popular vote in six out of the last seven elections.

But George McGovern intended for religious voices to be part of that coalition. He even spoke at Wheaton College in 1972 to try and win over young evangelicals. And–at least as far as white Protestantism goes–progressivism and religious faith have often seemed at odds since then.