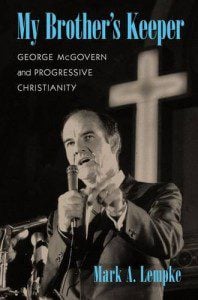

This is Part II of my interview with Mark Lempke, author of the new book My Brother’s Keeper: George McGovern and Progressive Christianity. See Part I here. –David

***

David Swartz: What was your biggest research find as you wrote this book?

Mark Lempke: I think the most historically significant discovery was the degree to which McGovern and antiwar mainline leaders were cross-boarding in 1972, to borrow a term from euchre. One of McGovern’s closest friends, James Armstrong, was the Methodist bishop of the Dakotas at the time. He started a group called Religious Leaders for McGovern and was able to convince some of the most prominent clergy and laity in the country to come out publicly for McGovern at a time when it was far from customary. William Sloane Coffin, Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Georgia Harkness (who taught McGovern in seminary), and Harvey Cox—all of these leading ecumenical voices decided in 1972 that supporting McGovern could be part of their prophetic responsibilities.

Mark Lempke: I think the most historically significant discovery was the degree to which McGovern and antiwar mainline leaders were cross-boarding in 1972, to borrow a term from euchre. One of McGovern’s closest friends, James Armstrong, was the Methodist bishop of the Dakotas at the time. He started a group called Religious Leaders for McGovern and was able to convince some of the most prominent clergy and laity in the country to come out publicly for McGovern at a time when it was far from customary. William Sloane Coffin, Rabbi Abraham Heschel, Georgia Harkness (who taught McGovern in seminary), and Harvey Cox—all of these leading ecumenical voices decided in 1972 that supporting McGovern could be part of their prophetic responsibilities.

There were a number of reasons for this. McGovern was “their kind of guy”: he was a Methodist churchman who at one point represented his denomination at the World Council of Churches. He and organizations like CALCAV and the Fellowship of Reconciliation shared a similar moral revulsion of the Vietnam War. But more than that, mainline and ecumenical leaders usually had the customary privilege of calling on the president and had for decades presumed to speak as America’s public conscience. From the turn of the century through LBJ’s term, mainline leaders could request a meeting with the president, and that request was usually granted. With Richard Nixon, they lost their seat at the table. He ignored them, Spiro Agnew frequently mocked them, and their role was subsumed by the “court evangelicals” who took part in President Nixon’s White House services and prayer breakfasts. In that sense, the mainline support for George McGovern wasn’t at all an act of confidence. To the contrary, it showed the degree to which they were losing influence—an early sign of the mainline’s waning cultural footprint.

D.S.: McGovern died about five years ago. If he were still alive, is he the kind of person you would want to get drinks with?

M.L.: I suppose he would be a better drinking buddy than Nixon, but that’s not saying much. Unlike his evangelical father, McGovern did drink, but cautiously so; alcoholism ran heavily in his family, and took the life of his daughter Terry in 1994. George McGovern wasn’t terribly extroverted and was never one of the Senate’s chummy “in-club” or men-about-town like Ted Kennedy or Chris Dodd. He was self-conscious about his moralistic streak, and would sometimes tell a salty joke or swear a bit at a party, if only to convince those around him that he wasn’t prudish. But he loved collecting facts and quotes from his days on the school debate team. If it was pub trivia night, I’d certainly want him on my team.

D.S.: What is it like to teach American history in Singapore?

M.L.: Teaching American history outside of the USA is a terrifically rewarding challenge. Unlike most of my stateside students, they haven’t learned much beforehand- U.S. history definitely isn’t part of their grammar school curriculum here. Instead, it’s remarkable how much young people across the world have learned about us through the osmosis of our pop culture. By watching How I Met Your Mother or Modern Family, by listening to Beyoncé records, or singing along with the Hamilton soundtrack, they have a reasonably adept understanding about the issues facing Americans. They know the South is culturally quite different from the Northeast. They are aware on some level that there was a great deal of social upheaval in the 1960s. I try to use these as starting points to engage them; they really are curious about the USA, even though many elements from our public life perplex them. Fortunately, almost everyone in Singapore speaks English, so there isn’t a language barrier between myself and my students.

D.S.: Anything Else?

M.L.: One of the most satisfying discoveries from researching this book has been the realization of how many great people there are studying American religion at this point in time. You and Brantley Gasaway broke new ground with your studies of the Evangelical Left, Kristin Kobes Du Mez is working on some great scholarship Hillary Clinton and her Methodism, Elesha Coffman’s book on The Christian Century, Benji Rolsky’s upcoming work on Norman Lear and the “Spiritual Left” of the 1980s. I could go on and on. This is a great time to be working in this field, and thank you for being a big part of what has made it so vibrant in recent years.