Transitions of power within the LDS Church are not very exciting. When the church president dies, the longest-serving member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles succeeds him.

If there’s any excitement in the process, it comes in the new president’s selection of his two counselors. The prior counselors revert to their position as members of the Quorum of the Twelve. The new president may choose them again, or he may choose others.

Otherwise, though, things are rather set in stone. Now that Thomas S. Monson has died, Russell M. Nelson will become the church’s seventeenth president.

When the church’s founding prophet and president Joseph Smith, Jr. was murdered in June 1844, things were not certain at all. Had Joseph’s brother Hyrum survived him, he would have almost certainly have become the church’s next leader. Hyrum may well have had broader support than Brigham Young garnered in the years after Joseph’s murder. The assassins who killed Joseph, however, also killed his brother.

In the wake of the murders, various Latter-day Saints had different ideas not only about the church’s future leadership, but about the church’s future more generally. Over the prior several years, Joseph Smith’s introduction of new doctrines and ordinances — especially polygamy — had created bitter fissures among church members. Moreover, over the church’s first fourteen years, Smith had created offices and quorums with his characteristic energy, but he left lines of authority unclear. The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, for instance, was initially tasked with governing the church outside of Zion. Did the apostles possess authority over those Saints in Nauvoo?

So how did Brigham Young emerge as the authority over most church members in the months and years ahead? The answer is complicated. Young was president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, a position he held because he was two weeks older than his good friend Heber C. Kimball.

But it wasn’t obvious to everyone that the Quorum of the Twelve or Young in particular should now assume a place of leadership. In the end, there were only two other serious possibilities (a third emerged in the early 1860s in the person of Joseph Smith III). Sidney Rigdon was the only surviving member of the church’s presidency. When he reached Nauvoo in early August 1844, he presented himself not as Smith’s successor, but as the church’s guardian. Rigdon, though, had been outside of Smith’s inner circle for some time. He was opposed to plural marriage, and he had not received the second anointing, the highest ordinance introduced by Joseph Smith.

On August 8, Rigdon made his case before a Sunday meeting of church members. Brigham Young then responded. Young carried the day on the basis of the ritual authority the apostles had received from Joseph, who had led them through the endowment, had sealed them in marriage, and had bestowed the second anointing on them and their wives. They had “the fulness of the priesthood.” Rigdon did not. Moreover, Young promised that the apostles would remain in Nauvoo, complete its under-construction temple, and lead church members through these same ordinances. He offered, in short, the fullness of salvation. “The keys of the Kingdom are in them,” Young said of the Twelve, “and you cant pluck it out.” After Young spoke, the Saints with near unanimity voted for the Twelve to lead the church.

There was one complication. Neither Rigdon nor Young presented himself as a second Joseph Smith, but a recent

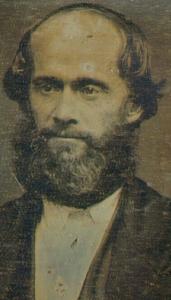

convert to the church did. A thirty-one-year-old lawyer and visionary named James Strang claimed to have a letter from Joseph Smith, dated nine days before his murder, appointing him the church’s next leader and instructing him to gather the church to southeastern Wisconsin. Strang dictated his own heavenly revelations and unearthed his own set of buried records. Although his letter was a not very sophisticated forgery, Strang attracted hundreds of followers over the next several years. For a time, Strang was a real competitor to Brigham Young.

Meanwhile, the events of August 1844 had not fully settled the issue of succession for those Saints who followed Brigham Young to the West. Young quickly assumed authority. He was the de facto president of the church, but only de facto. Only after Young led the vanguard pioneer group to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 did he ask the other apostles to reconstitute a church presidency, with himself as president with two counselors of his choosing.

Young’s proposal sparked a series of heated meetings, in large part because of the vociferous opposition of Orson Pratt, who thought that Young should remain more like the speaker of the House of Representatives than a president. “Shit on Congress” was Young’s retort. Young insisted that he would lead the church untrammeled, and he promised that God would give him revelations as God had given Joseph. Eventually, at a December 5, 1847, meeting Pratt gave way.

After Pratt conceded, the mood changed from contention to celebration. Late at night, the apostles retired to Orson Hyde’s cabin, ate dinner, sang “the Pioneer song,” and drank “Jerusalem Wine & delightful Strawberry wine.” Presumably Hyde had brought the former from his mission to Jerusalem in the early 1840s. “Our souls,” recorded clerk Thomas Bullock, “[were] all rejoicing in the Lord.” A few weeks later, a church assembly sustained the decision. There were no dissenting votes. The assembled Saints, striking their right hands into their left palms after every word, joined in a threefold shout of “Hosanah! Hosanah! Hosanah! To God and the Lamb! Amen! Amen! Amen! and Amen!”

In the weeks ahead, the Quorum of the Twelve will unanimously choose to reorganize a First Presidency and select Russell M. Nelson as church president. The church as a whole will sustain him as such at its next general conference. No strawberry wine, however.