These are odd days. In 5 minutes I may come to know your appearance, birthdate, hometown, interests, likes and dislikes, favorite movies, recent thoughts, friends, family, acquaintances, occupations, and relationship status — all without ever encountering you.

These are odd days. In 5 minutes I may come to know your appearance, birthdate, hometown, interests, likes and dislikes, favorite movies, recent thoughts, friends, family, acquaintances, occupations, and relationship status — all without ever encountering you.

These are delightful days wherein an Internet connection enables me and millions to observe a stranger’s genitalia, days I may know the intimate details of another person to the point of their nakedness — and never know them. I have 500 Facebook friends — about 20 come to mind. I have nodded enthusiastically to the cry of “connectedness!” as the chief virtue of the smart-phone — and have never felt less connected.

These are media days. We contain within ourselves the sex lives, divorces and pregnancies — the real heavy heart-to-heart stuff — of half a hundred celebrities we will never meet. We are more informed of more genocides and catastrophes rippling through more foreign countries, the names of which we cannot pronounce — and we scarcely care. In short, we are happily drowning in a deluge of knowledge-about people, which provides us the illusion of having encountered them.

The person is known outside-in, through an observable exterior — words, gestures, expressions, and actions — to an unobservable interior life — how they feel, what they think, what they mean and who they are. The sojourn outside-in is the terrible miracle of human interaction. We never know the man we meet. We can never obtain any sort of finished knowledge of his interior life. We can never completely grasp the soul that animates a man’s outer expressions. Rather, in the dark light of another person, we live in the constant state of glimpsing. We encounter them in every moment. We strive towards them. We catch glimmers of the person as we catch the sun through clouds or breaking itself on a lake. Our neighbor’s objective, outer expressions constantly reveal to us a life we can never inhabit, can never have, an inexhaustible mystery we can never fully know.

How obvious this is in love, when we willfully enter into the atmosphere of another person and strive to reach their “hearts,” their “souls,” their “entire person” — that inner life grasped through the outer. We feel the beloved’s highs, lows, despairs, hopes, and all through nearly imperceptible scents, sighs, sights and flashes of intuition. Sings Paul Simon:

She comes back to tell me she’s gone.

As if I didn’t know that,

as if I didn’t know my own bed.

As if I never noticed

the way she brushed her hair from her forehead.

Marvel, how the minute movement of hand to hair contains multitudes, indeed, how it can contain the whole fate of the day, the year, or the entire relationship. We get it wrong as often as right. We gaze in hope of glimpses, and find that just when we think we know, that we are familiar, some new revelation will come, some word or action, and we are plunged back into wonderful and painful awareness that the person is not a thing known, but a mystery revealed in revelations that never annul the mystery. To know a person is to come to know that I do not know. Here less is really more.

But these are odd days. We offer outsides that are not necessarily expressions of insides, exteriors that are not the direct revelation of unobtainable interiors, heaps of knowledge-about that are not necessarily invitations to encounter the person. What is this Facebook-knowledge, this survey-stuff, these texting, sexting, profile-pictured, chatting revelations? What is it to know a deluge about an un-encountered person? It is not to know them at all, for factual, about-knowledge could equally be knowledge about any other person. What is it to deal in the objective expressions of other people that are not direct encounters with their entire person — the selfies, status-updates and such, or the images of starving children and sad celebrities we’ve never met and never will? It is the estrangement of the exterior life from the interior life which expresses it.

When we live on the level of knowledge-about, we remove the difficulty from personal relationship by removing the person. What we see is what we get. We do not strive to glimpse the person expressed through the millionth photo of Jennifer Aniston, the video of the porn-star or the politician, the reported weekly tragedy, or the anonymous Facebook profile picture. We do not hazard the terrain from the outside to the interior — and why would we? The two have been estranged.

This is hardly a bad thing in itself. What hurts is the illusion that this knowledge-about amounts to an encounter of the person. 500 friends on Facebook and miserably alone, connected in every capacity and floating in the void, informed as all hell and apathetic in the extreme — this is the foul fruit of my generation, that in an Internet-age we ought to be living in a world of profound connection and relation, but are not.

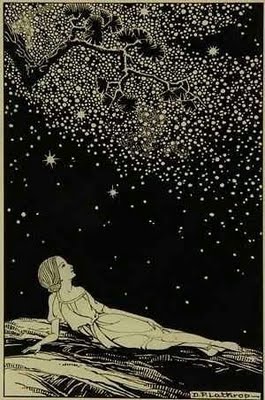

We discussed how the absence of the loved one is actually the concentration of their presence. To this strangeness I would add that, as absence is presence in the person, distance is nearness. Being pressed to the facts of about another person, feeling the warmth of their details, knowing them objectively in the immense nearness of our age, all this may create an illusion that we are actually encountering the person, when in reality we are quite alone, wallowing in lists and characteristics — in stuff that could equally be about another. But grant a little distance. Give a little air. Allow in the observed an unknowability that is the wellspring of all her outer expressions. Suddenly the person slides into focus — precisely as a mystery. The thesis then: If the person is an unknowable subject who gives himself in marvelous glimpses, then distance, which admits that we do not know him, is nearer to the truth about him than any objective nearness. If the person is a really, truly a mystery, then admitting we know less is knowing more. Consider the stars.

When we reduce them to what we know about them, when we feign a nearness that is really a list of objective characteristics — calling them spheres resulting from the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula and the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium — we lose the reality, that primordial encounter the stars that makes us care enough to study them in the first place. We list things about the stars, and in the smirk of superiority, pretend that this knowledge-about ever equates to a knowledge-of — to encounter. But stars merely known-about are easily ignored. Who hasn’t felt the let-down of demystification, told that the stars are just gas, love just a cocktail of the following chemicals, the Northern Lights just the collision of particles.

Maintain the real, felt distance between us and the stars. Acknowledge the nightly experience. We are given next to nothing of them. They are pinpoints of light, singularities — simple spots. The child gazing at the things is washed in distance, unknowability — in mystery. His knowledge-about is made minimal by distance, but this distance is nearness, for it is precisely in this distance that the stars matter, that they mean. He barely knows about the stars, but he encounters them hugely, and what good is all subsequent knowledge and learning-about — which is certainly very good — if it does not serve this meat-and-bones-and-spirit encounter of the thing itself?

Maintain the real, felt distance between us and the stars. Acknowledge the nightly experience. We are given next to nothing of them. They are pinpoints of light, singularities — simple spots. The child gazing at the things is washed in distance, unknowability — in mystery. His knowledge-about is made minimal by distance, but this distance is nearness, for it is precisely in this distance that the stars matter, that they mean. He barely knows about the stars, but he encounters them hugely, and what good is all subsequent knowledge and learning-about — which is certainly very good — if it does not serve this meat-and-bones-and-spirit encounter of the thing itself?

Far from the stars, we make gods of them. Near — their divinity flickers. There are few mythologies of thermonuclear reaction. I know of no helium deities. To maintain the mystery of the stars is to maintain our real, human relation to them. In this stretching, aching distance we find ourselves closer to the pinpricks in the ether-sphere than in any number of collected details. Distance is nearness.

But how much sooner than the stars we should make gods of people, fantastic people, with souls and interior lives light-years away from our powers of observation! If we could grant a little distance, acknowledge the hidden in a world of constant display, the subjective in an objectified age — how much closer we would come to the truth. People are not known through observation. People are known through love, which races to find the unfindable interior, to encounter the entire person, the person we can never fully know, but can only glimpse. These are odd days, Internet-times, in which I believe a superhuman effort is necessary to disavow the illusion that knowledge-about is an encounter with the person. I believe this effort is called modesty. But that’s for another time.