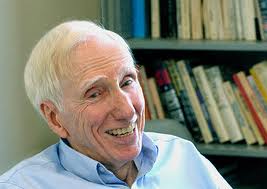

Sitting in his office perched above the hills in Berkeley, California, yesterday I got to meet one of the legends of sociology: Robert Bellah. Among other accomplishments, Bellah’s co-authored book Habits of the Heart from 1985 has sold half a million copies, his essay Civil Religion in America is widely discussed and cited, and his very recent magnum opus Religion in Human Evolution has caused quite a buzz in the academic world. (See the lively discussion of it on the Immanent Frame).

Now in his 80s, Bellah greeted me warmly in his home office. He’s quite tall—around 6 foot 4 inches, and he has a bright smile. His first words were a very personal introduction, saying,

“My wife died about 2 years ago after 61 years of marriage.” During our hour and a half conversation, he must have mentioned his love for his wife at least a half dozen times, telling me, “She really was my other half. I really believe the Biblical narrative that when people get married (at least in good marriages), it really is like a one-flesh union of two people. I felt like half of me was amputated when she died. I couldn’t write for about a year, but I could read. I felt this deep desire to be united with her, but my work, my children, and my grandchildren keep me going.”

Bellah sometimes feels that the popularity of his essay, “Civil Religion in America,” takes attention away from his other important works, even calling that article “that darned piece on civil religion!” However, I explained I assign Bellah’s Civil Religion essay and show students John F. Kennedy’s 1961 Presidential Inaugural Address that Bellah analyzes in “that darned piece!” Although Kennedy does mention “Almighty God” or Bible verses about 5 times in that speech, he refers to the nation as having a sacred mission at least 25 times. As Bellah so aptly describes and Kennedy’s speech perfectly illustrates, our nationality is not just something that gives us rights and responsibilities, our nationality is a moral, sacred belonging. Presidents before and after Kennedy rarely proselytize their particular religion, but they all describe the nation as sacred. Simply showing students that group belonging (like nationality) is not always a matter of personal choice and that those group belongings have powerful moral narratives opens their eyes to how profoundly social human beings are and how human action has a moral dimension.

One concern about his famous civil religion essay, Bellah said, is that readers often do not know he wrote that essay in part motivated by his critique of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. As Bellah explained,

“I agree, in good Durkheimian fashion, that for Americans the nation is seen as sacred. But that can and often has been interpreted to mean that it cannot be criticized: ‘my country right or wrong.’ Since my essay came out of my deep criticism of American involvement in Vietnam, which was going on at the time, that can’t be what I meant. I was arguing that America’s commitment to an authority higher than the nation meant it should always be criticized when it falls short of those standards.”

Most of my students have only heard the Camelot stories of JFK and have no idea that he escalated the Vietnam War. But a close analysis of his words show exactly what Bellah says: JFK elevates the nation as sacred in part to justify the arms race and the war on communism. American citizens are not just passive recipients of the moral messages of their leaders, we should be ready to criticize those moral messages when needed and actively construct alternative moral identities.

I explained to Bellah how in my current class on positive sociology, I’m trying to get students to understand the moral narratives that underlie many social groups. In one assignment, they have to write about their experience in a group ritual, whether that is the UNC-Duke basketball game, a religious service, a sorority, or another social group with rituals. What activities, symbols, narratives contribute to group identity, moral narratives and collective effervescence? How do their experiences confirm or expand upon our readings from Emile Durkheim and Jonathan Haidt on moral narratives and social rituals?

I explained to Bellah how in my current class on positive sociology, I’m trying to get students to understand the moral narratives that underlie many social groups. In one assignment, they have to write about their experience in a group ritual, whether that is the UNC-Duke basketball game, a religious service, a sorority, or another social group with rituals. What activities, symbols, narratives contribute to group identity, moral narratives and collective effervescence? How do their experiences confirm or expand upon our readings from Emile Durkheim and Jonathan Haidt on moral narratives and social rituals?

In their next assignments, my students will use readings from Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America to analyze how well their experiences at UNC line up with the mission of UNC as explained in its charter. The 1789 charter which created the University of North Carolina begins:

“Whereas in all well-regulated governments it is the indispensable duty of every legislature to consult the happiness of the rising generation and endeavor to fit them for an honorable discharge of the social duties of life, by paying the strictest attention to their education…”

How do Tocqueville’s writings shed light on UNC’s mission statement and the actual community at UNC in students’ own experience? Do voluntary associations such as campus organizations, housing arrangements, clubs, and other social groups at UNC contribute to the well-being of individuals, the state of North Carolina and the nation? Or do they not contribute at all?

Bellah expressed great concern that today’s generation of college students is so worried about accruing debt and finding jobs when they graduate that they have lost sight of the larger purpose of being a university student. Bellah’s vision of college is not just about acquiring knowledge or gaining a credential: rather, going to college should be a larger introduction to life; college should educate citizens who have a sense of responsibility towards the rest of the world. Bellah fears that today’s social media tools like Facebook provide lots of superficial social contact but little of the group formation that form people’s sense of belonging to a larger world. In fact, in my students’ first essay on happiness, two students wrote convincing papers about how obsessions with Facebook and other social media tools can detract from deep friendship. When you know lots of tidbits about hundreds of people you have never met, and when you are constantly checking everyone’s status updates, how do you form the friendships that will generate practical wisdom and other virtues?

Bellah expressed great concern that today’s generation of college students is so worried about accruing debt and finding jobs when they graduate that they have lost sight of the larger purpose of being a university student. Bellah’s vision of college is not just about acquiring knowledge or gaining a credential: rather, going to college should be a larger introduction to life; college should educate citizens who have a sense of responsibility towards the rest of the world. Bellah fears that today’s social media tools like Facebook provide lots of superficial social contact but little of the group formation that form people’s sense of belonging to a larger world. In fact, in my students’ first essay on happiness, two students wrote convincing papers about how obsessions with Facebook and other social media tools can detract from deep friendship. When you know lots of tidbits about hundreds of people you have never met, and when you are constantly checking everyone’s status updates, how do you form the friendships that will generate practical wisdom and other virtues?

How do we recover a vision of the common good? Bellah told me he had just started reading Catholic teachings on human rights and the common good, beginning with one of the foundational documents of Vatican II, Guadium et spes. Bellah was “utterly blown away” by the Gaudium et spes’s unflinching defense of human dignity combined with a robust vision of social justice. It’s hard, Bellah said, to avoid an individualistic or utilitarian vision of human rights, but Guadium et spes articulates how human rights and the common good reinforce each other. What do I think of Benedict XVI’s social encyclical Caritas in veritate, Bellah asked me?

Since I had previously read numerous of Benedict XVI’s books on Christology, theology, and secularization, I was already familiar with various themes of his thought which appear in Caritas in veritate: that truth is objective rather than relative, and that virtue must be both in the heart and in action. As such, the church’s mission of charity can never be private; the church’s mission of charity is public—it is oriented to the greater good of all, regardless of religious creed. Hence, the state and church are inter-dependent in their work for the common good, something that is hard for people to understand if they think religion must only be a private matter.

I explained to Bellah that English sociologist Margaret Archer has a fantastic essay, “Caritas in veritate and Social Love” (International Journal of Public Theology 5 (2011), pp. 273–295) which is the best integration of sociological insights on human persons and social structures with Catholic reflections on human dignity and the common good. Archer masterfully shows how personal identity and the common good can, under the right conditions, build an ever-expanding civilization of love envisioned in Catholic social teaching.

Since Bellah told me one thing that facilitated his writing of Religion and Human Evolution was email correspondence and friendships with leading experts in fields that are new to him, like biology and animal evolution, I offered to be his email correspondent and friend if he wants to read more about Catholic social teaching. Even if he never takes me up on that offer, I’ll never forget the afternoon I spent in his home office as he reflected on his major intellectual works, the future of American youth, and his six decade long love affair with his wife that was transformed, but not ended, by her death.