Ridley Scott, is the director of such classic films as Alien, Blade Runner, Thelma & Louise, and Gladiator.  So when I heard that Scott, who is a self-described atheist, had been given a $140 million budget to make a film of the biblical Exodus story, my curiosity was piqued. It’s been almost sixty years, since Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, so we were probably due for a update using twenty-first century special effects.

So when I heard that Scott, who is a self-described atheist, had been given a $140 million budget to make a film of the biblical Exodus story, my curiosity was piqued. It’s been almost sixty years, since Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, so we were probably due for a update using twenty-first century special effects.

Now, if you, like me, are a huge religion nerd, then this film is perhaps worth your $12. But be forewarned that this movie, while not terrible, is no masterpiece. According to the website Rotten Tomatoes, only 28% of critics and 45% of audience members have given it a positive review. Magin, my wife, would tell you to skip Exodus and instead see the film Wild, based on Cheryl Strayed’s widely-praised memoir, and which is getting 92% approval. I’ll say a bit more about the film later, but first allow me to situate us historically.

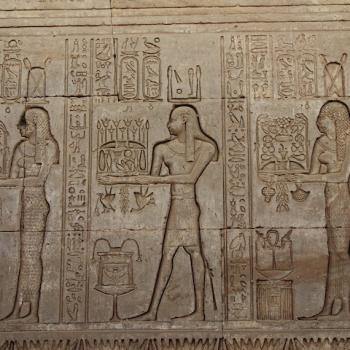

In Genesis, the first book of the Bible, the ancestral legends of Abraham and Sarah (and Hagar); Rebekah and Isaac; Jacob and Leah, Zilpah, Rachel, Bilhah are set approximately 4,000 years ago, which would date the “historical Abraham” to around 2,000 B.C.E. The famine in Canaan (which led the Israelites to Egypt in search of food and which resulted in their eventual enslavement) would have happened around 1,700 B.C.E., marking the beginning of four hundred years of Israelite slavery in Egypt. And the Exodus, would’ve been around 1,300 B.C.E.

And I’m taking the time to give a shout out for biblical literacy because of the tremendous impact the Bible has had and continues to have on our history and culture. In particular, scholars have argued that Exodus may be the single most important and influential book in the Bible — both for better and worse:

Many early American settlers understood their flight from Europe and settlement in America as a new exodus. Later, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson recommended that the great seal of the United States depict Moses leading the Israelites across the parted sea as a symbol of the American experience. [The shadow side of this view is that Native Americans were cast as the New Canaanites, helping justify abusing and stealing the land from the indigenous groups.]

African-Americans in the U.S., hoping for freedom in the 19th-century and fighting for civil rights in the 20th century, likewise saw themselves as reliving the Israelite experience.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the mass departure of hundreds of thousands of Jews from the Soviet Union was known as “Operation Exodus.” (Jewish Study Bible, 102-107)

The power of this archetypal story to inspire liberation movements continues today.

And although the basic story of freedom from oppression is told in Scott’s new film, one of my biggest disappointments is that the movie doesn’t fulfill the promise of its subtitle (Exodus: Gods and Kings). At the core of the Exodus story is a conflict between competing deities: the Hebrew tribal god Yahweh vs. the Egyptian gods, which include Pharaoh himself as divine.

But the story is actually much more interesting and complicated than that. Although we have come to think of Judaism as monotheistic, Judaism did not definitely affirm the existence of only one God until the mid-6th-century B.C.E. around the time of the Babylonian exile, more than 700 years after the Exodus from Egypt. For example, by the time of Isaiah 44:6-8 from the Babylonian exile, we hear clear monotheism,

6 Thus says the Lord, the King of Israel, and his Redeemer, the Lord of hosts: I am the first and I am the last; besides me there is no god. 7 Who is like me? Let them proclaim it, let them declare and set it forth before me. Who has announced from of old the things to come? Let them tell us what is yet to be. 8 Do not fear, or be afraid; have I not told you from of old and declared it? You are my witnesses! Is there any god besides me? There is no other rock; I know not one.

But before then, Israelite religion was henotheistic, meaning “the worship of one god without denying the existence of other gods.” The Greek words heis and monos can both mean “one,” but heis has the connotation of one in a sequence of numbers, and monos has a connotation of “alone” and “single.” Notice, for example, to the henotheism in these three verses:

Exodus 20:2-3, “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery; you shall have no other gods before me.”

Deuteronomy 32:8-9, “When the Most High apportioned the nations, when he divided humankind, he fixed the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the gods; the Lord’s own portion was his people, Jacob his allotted share.”

Joshua 24:2, 15, “And Joshua said to all the people, ‘Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: Long ago your ancestors…lived beyond the Euphrates and served other gods…. but as for me and my household, we will serve the Lord.”

A close reading of the Bible will blow your mind, which is why I’m convinced that most people who say they want to “return to biblical values” have never actually read most of the Bible.

I’ll give you just one more example of the untapped potential in that subtitle Exodus: Gods and Kings. It turns out that Yahweh (who is depicted as a male) had a female consort named Asherah. So while Jesus likely did not have a wife, it turns out that God did! Yahweh and Asherah were a “very popular divine couple…prior to the religious changes introduced by King Josiah in 622 BCE” (Jeffrey Kripal, Comparing Religions, 180). I’ll have to save further details for a future post, but in addition to archeological evidence, there are six direct references to Asherah worship scattered through the biblical books of Kings:

1 Kings 15:13, “He also removed his mother Maacah from being queen mother, because she had made an abominable image for Asherah; Asa cut down her image and burned it at the Wadi Kidron.” [Parallel: 2 Chronicles 15:16, “King Asa even removed his mother Maacah from being queen mother because she had made an abominable image for Asherah. Asa cut down her image, crushed it, and burned it at the Wadi Kidron.”]

1 Kings 18:19, “Now therefore have all Israel assemble for me at Mount Carmel, with the four hundred fifty prophets of Baal and the four hundred prophets of Asherah, who eat at Jezebel’s table.”

2 Kings 21:7, “The carved image of Asherah that he had made he set in the house of which the Lord said to David and to his son Solomon, “In this house, and in Jerusalem, which I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel, I will put my name forever;”

2 Kings 23:4, “The king commanded the high priest Hilkiah, the priests of the second order, and the guardians of the threshold, to bring out of the temple of the Lord all the vessels made for Baal, for Asherah, and for all the host of heaven; he burned them outside Jerusalem in the fields of the Kidron, and carried their ashes to Bethel.”

2 Kings 23:6, “He brought out the image of Asherah from the house of the Lord, outside Jerusalem, to the Wadi Kidron, burned it at the Wadi Kidron, beat it to dust and threw the dust of it upon the graves of the common people.”

2 Kings 23:7, “He broke down the houses of the male temple prostitutes that were in the house of the Lord, where the women did weaving for Asherah.”

All that to say, I would’ve been a lot happier if Ridley Scott’s film had explore the fuller implication of all those “Gods and Kings,” but he did at least give me a good excuse to share some of this history with you.

All that to say, I would’ve been a lot happier if Ridley Scott’s film had explore the fuller implication of all those “Gods and Kings,” but he did at least give me a good excuse to share some of this history with you.

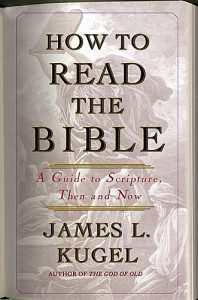

But also to address my own title of “Did the Exodus Happen?” I would be remiss if I failed to address what some of today’s best biblical scholarship says about separating myth from legend in the Exodus story. Drawing on the work of one of my favorite biblical scholars, the emeritus Harvard professor James Kugel, in his excellent book How to Read the Bible, writes that there may well be,

a kernel of historical truth in the exodus account. It may be that the story was originally much more localized and involved far fewer people — perhaps only a small band of escapees from Egyptian servitude…. [T]he exodus theme is especially prominent in northern [Israelite] texts. For that reason, some have supposed that the whole exodus tradition was originally found only among some of the northern tribes.… After David succeeded in united the twelve tribes under one flag, this formerly local bit of history would have become part of the common heritage of all tribes.

Certainly such a turn of events would not be unparalleled. After all, Americans [of many] generations were taught in school about “our Pilgrim fathers” who came over on the Mayflower or “our Founding Fathers”…whereas the overwhelming majority of Americans could hardly be said to be descend from this idealized ancestor group…. It is not hard to imagine, scholars says, that a similarly pious theme [of the Exodus story] came to be transferred from the experience of a few to the foundation myth of an entire nation. (232)

And scholars tell us that what follows from this insight that there was no mass exodus from Egypt is that the Israelites were always already in Canaan. In other words, the Israelites were Canaanites. Joshua (Moses’ successor) did not lead an invasion from the outside; instead, there was in all likelihood an internal insurrection in which one group of Canaanites who worshiped a god called Yahweh came to dominate the land (382, 385). To limit myself to just one among many pieces of evidence for this theory, the word “El” in Isra-el is also the name of the Canaanite supreme deity: “Israel’s God was actually a development of…the old head of the Canaanite pantheon (423-424).

Some of you may know the word syncretism (meaning the ways that religions all borrow from and influence one another), and the history of religions shows us that, “It’s all syncretism, all the way down.” In our current holiday season, the pagan roots of the Christmas tree and the choice of celebrating Jesus’ birth at the same time as the Winter Solstice are two other prime examples of the pervasive influence of religious syncretism.

For now, I’ll conclude with a few words about the relevance of the archetypal Exodus story today. To do so, it is important to name that the best reason not to see Ridley Scott’s new version of the Exodus story is the racist casting, which is ironic since it is a story about the liberation from slavery. As commentator David Dennis has written,

all the main characters are White. Moses is White [and played by Christian Bale, so it turns out Moses is Batman, which is arguably at least an improvement from Charlton Heston]… The Pharaoh is White. Tuya [Pharoah’s mother, played by Sigourney Weaver] is super White and Joshua is Jesse Pinkman [from Breaking Bad]. Not only are these characters who are supposed to be Africans White, they’re not even remotely tan….the only thing Black about the main cast was their eyeliner. Not only are all the main characters White, but the servants, thieves and assassins are played by Africans.

Even worse, when called out, Ridley Scott said, “I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely  on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such. I’m just not going to get it financed. So the question doesn’t even come up.” So, you may want to save your money, and instead see Wild or the new film Selma about MLK, which is coming out Christmas Day — both of which are also getting much higher reviews.

on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such. I’m just not going to get it financed. So the question doesn’t even come up.” So, you may want to save your money, and instead see Wild or the new film Selma about MLK, which is coming out Christmas Day — both of which are also getting much higher reviews.

Nevertheless, as we reflected on earlier, there are many ways in which the Exodus archetype influenced the Civil Rights Movement, casting Dr. King as the new Moses. And as we near the 50th Anniversary of the March from Selma to Montgomery and work to discern our role in the continuing struggle for racial justice in our country, if you haven’t seen it, I recommend the insightful interview with comedian Chris Rock that was in a recent issue of New York Magazine. In thinking about the meaning of the Exodus story for today, I was particularly struck by this section in the Chris Rock interview in which he said:

When we talk about race relations in America or racial progress, it’s all nonsense. There are no race relations. White people were crazy. Now they’re not as crazy. To say that black people have made progress would be to say they deserve what happened to them before. So, to say Obama is progress is saying that he’s the first black person that is qualified to be president. That’s not black progress. That’s white progress. There’s been black people qualified to be president for hundreds of years.

If you saw Tina Turner and Ike having a lovely breakfast over there, would you say their relationship’s improved? Some people would. But a smart person would go, “Oh, he stopped punching her in the face.” It’s not up to her.…

You know, my kids are smart, educated, beautiful, polite children. There have been smart, educated, beautiful, polite black children for hundreds of years. The advantage that my children have is that my children are encountering the nicest white people that America has ever produced. Let’s hope America keeps producing nicer white people.

Part of producing nicer white people is continuing to raise awareness about the ongoing, systemic racism in our country:

- It means taking the time to read vitally important books like Michele Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in an Age of Colorblindness.

- I also recommend the work of Tim Wise, such as his book White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son.

- Or if you can only make time for one article at this point, challenge yourself to read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ devastating piece in The Atlantic on “The Case for Reparations,” and don’t assume in advance that you know what he is going to say.

All such anti-racist, anti-oppressive resources point us toward what it means for today to learn from the Exodus archetype of communal liberation from oppression.

In that spirit, I will end for now, with a reflection from my colleague The Rev. Rosemary Bray McNatt:

At this time of holy unrest, give us the peace that comes

When we know why we struggle and what we struggle for.Spirit of life in all its fullness, renew us and remind us that

we who have answered your call

Were never promised ease, or wealth, or appreciation….

Remind us that we serve the great cause of justice, not ourselves.Give us, we pray, a true joy in the community we form each time we gather

To pray, to march, to interrupt ordinary time to create sacred time, a time to help others awaken to what is so very wrong in our world.Help us to be kind, even to those with whom we struggle.

Help us to be, in the raising of our voices and the marching of our feet,

agents of a radical love that holds us all.Finally, help us to be grateful, grateful to live in these times

when great works of justice await our hands and hearts and minds and spirit.

Prepare us so that we might do all that is in our power to change this world,

so that the whole creation might see Beloved Community,

not tomorrow, but today.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles