Some of you may remember the controversy in the late 1980s when the film director Martin Scorsese released his screen adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel The Last Temptation of Christ. One reason I remember the uproar is because my father owned a video rental business, and when this film was released on VHS, local pastors in our hometown of Florence, South Carolina petitioned my dad to remove the film from the shelves because they perceived it as offensive. Although I can count on one hand the number of times that I saw my father attend church, he capitulated to the protests of these conservative religious leaders. He told me that he based his decision on the adage “Choose your battles wisely.”

This VHS tape sat abandoned for many years on the shelf underneath the TV in my family’s den. But about a decade later, during my sophomore year of college, as my personal “Quest for the Historical Jesus” began in earnest, I finally popped that dusty tape into the VCR. The most provocative part of the film is the idea that Jesus underwent a last temptation during the crucifixion in which he envisions himself forsaking the cross, marrying Mary Magdalene, and creating a family with her. Even though Jesus is depicted at the end of the film as overcoming this tempting vision of choosing the domestic life over a martyr’s death, the idea that Jesus even experienced sexual temptation scandalized many conservative Christians — not to mention how they felt about the scene in which Jesus fantasizes about consummating his marriage to Mary Magdalene.

Overall I found the film to be a fascinating speculation about what it means to believe that Jesus was fully human, just like the rest of us. And more recently, a few years ago while listening to the contemporary wisdom teacher Cynthia Bourgeault speak about her 2010 book The Meaning of Mary Magdalene, I thought to myself that, perhaps the “The Last Temptation of Christ” should be retitled “The Best Temptation of Christ.”

Whereas many religious traditions uphold celibate monasticism as the ideal, Bourgeault (who is inspired by the Mary Magdalene tradition) argues, for an understanding of human relationships as an equally transformative “sacred path” (216). If you are called to celibacy that can and has been transformative for many, but so too can relationships and marriage. And perhaps if the Romans had not executed Jesus for insurrection, he might have married Mary Magdalene and had children. And a whole new set of teachings might have emerged from that bond. As anyone who has ever been in a longterm relationship can attest, Jesus’s teaching to “love your neighbor” is easier in the abstract and in the short term (Jesus was itinerant!) than loving one particular person day after day, after day for the rest of your life (as well as remaining lovable yourself). And although there is tremendous value in many parts of Jesus’s life and teachings, for anyone discerning how to love another person for a lifetime, Jesus — who died tragically young and single at around the age of 30 — is not our best marriage counselor.

That being said, one major emphasis of my own tradition of Unitarian Universalism is the teaching that Jesus is fully human — and that to whatever extent Jesus manifested the sacred or the divine, we too have that same potential. As one Jewish feminist biblical scholar has written, taking into account all that we know in the early twenty-first century, our invitation to still “value Jesus [even] if he was just a Jew who chose to emphasize certain ideas and values in the Jewish tradition but did not invent or have a monopoly on them” (122).

And if Jesus was fully human, that means that there was a sexual component to his being. As the poet William Blake (1757-1827) said more than two centuries ago: “The Bible must be shaken upside down before it will yield all its secrets. The priests have censored and clipped and mangled: they give us a celibate Jesus born of a virgin without the slightest ‘stain’ of sexual contact, which is blasphemes nonsense” (29). I love that what Blake deems blasphemous is not Mary Magdalene as the last/best temptation of Christ; rather, for Blake, the blasphemy is neutering Jesus.

And I invite you to consider that the consistent fascination with Mary Magdalene through the centuries is because Mary Magdalene reminds us of a huge shadow side of the Christian tradition: the repression of both women’s experience in particular and of sexuality generally. Along these lines, this post is inspired by the landmark book by the feminist biblical scholar Jane Schaberg from about a decade ago titled The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene. Following the trajectory of Schaberg’s work, I would like to invite us to consider what it might look like to reconsider the Christian tradition from the perspective of women’s experience, using Mary Magdalene as our guide.

I’ve also posted previously about my interest in the work of the religion scholar Jeffrey Kripal, who teaches at Rice University in Houston. Kripal has written about his experience that was similar to the “Last (or best!) Temptation of Christ.” Just as those fictional works imagine Jesus having a vision of escaping his crucifixion to start a family with Mary Magdalene, Kripal, while he was in seminary to become a Roman Catholic priest, had a powerful dream in which he was swimming and had to choose which side of the river to swim toward. On one side was Jesus. On the other side was a beautiful woman.

The dream forced him to confront in a way that he had not previously that his sexuality was a central part of himself and his spirituality that he could not repress. But given the current “symbolic and institutional system” of Roman Catholicism (which allows only celibate males to ascend to the highest ranks of religious leadership), he saw his choice as drawn starkly “between a celibate religious or a secular [heterosexual] life.” Here we can see the long shadow of the repressed Magdalene archetype within the Christian tradition: There was no room for him as a self-described “active, heterosexual male” within a Roman Catholic seminary. Accordingly, he wrote in his journal: “This is just perfect — I’m caught…between a sexless Virgin and a homoerotic Jesus” (155).

I don’t quote that last line to be offensive. Rather, I am very seriously inviting us to consider the dynamics of the Christian tradition given what we know about modern psychoanalysis. From a post-Freudian perspective, Kripal’s dream was his unconscious confronting him an aspect of himself he had been repressing. Freud calls this sublimination. As Mark Jordan (who grew up gay and Catholic and is now a Professor of Christian Thought at Harvard) has written, there is a “paradox created by an officially homophobic religion in which an all male clergy sacrifices male flesh before images of God as an almost naked man.” There is a lot more to be said about this insight — and many more examples that I could give at another time, particularly in the writings of the Christian mystics through the ages — but for now suffice is to say that if you take one step back to observe the religious landscape, there are unavoidable, unconscious psycho-sexual dynamics that are in play when one is part of a religion in which one is commanded to love a God, who is always pictured as male. And that unconscious relationship to the male deity plays out differently, depending on where you find yourself on the spectrum of masculine and feminine, heterosexual or homosexual. And as Kripal moved away from his pursuit of the priesthood and toward academia, his scholarship led him to a study of the Hindu tradition which has a strong component of embracing a scared heterosexuality — as can be seen in the Tantric tradition, books such as the Kama Sutra, and the explicit carvings on the sides of many Temples.

Returning to our guide of Mary Magdalene, she also challenges us about how problematic it is to put a single male at the center of a religious tradition. Such a choice almost inevitability leads both to sexism (the favoring of the male) and to individualism. Indeed, feminist scholar Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza has argued that as important as the Quest for the Historical Jesus has been, it still troublingly puts all the focus on the identity of one man (11).

And the orthodox reading of the Christian tradition is that an asexual Jesus passed on the mantle of leadership to a series of celibate males at the head of a top-down hierarchy. But there are many other ways of interpreting Christianity history. We have only to consider verses such as Matthew 8:14 to see that, “When Jesus entered Peter’s house, he saw his mother-in-law lying in bed with a fever.” The last time I checked, the only way you get a mother-in-law is to get married. So if Peter was the “first pope,” then the first pope had a wife.

And if you read the Gospel of John, the “Beloved Disciple” is depicted as a more important leader than Peter. If you read the Book of James, Jesus’s brother James seems like the primary leader after Jesus’s death. Likewise for Paul’s letters (he seems most important there) and the same for the Gospel of Thomas or the Gospel of Mary; therein the primary leader seems to be Thomas or Mary respectively. As you begin to separate out these competing claims of authority, the question becomes, in the words of the historical Jesus scholar John Dominic Crossan, “How Many Years Was Easter Sunday” (190)? What he means is the traditions around “Easter” were not one story of one morning told and retold in an unchanging way until today, but were rather decades in the making — both for the date of Easter (which seems not to have been set until at least a full century after Jesus’ death) and for the stories about Jesus’ resurrection which were formed in the telling and retelling as his various followers struggled to make sense of his death. And these stories were told in different ways by the different communities of Jesus followers that gathered around Peter, James, John, Mary, Thomas, and other competing leaders in the wake of Jesus’s death.

As the Harvard historian of religion Karen King puts it in her book The Gospel of Mary Magdala:

The beginning is often portrayed as the ideal to which Christianity should aspire and conform. Here Jesus spoke to his disciples and the gospel was preached in truth. Here the churches were formed in the power of the Spirit and Christians lived in unity and love with one another…. But what happens if we tell the story differently? What if the beginning was a time of grappling and experimentation? What if the meaning of the gospel was not clear and Christians struggled to understand who Jesus was…?” (158)

And although it was indeed the case that there was “Original Diversity” at the beginning of the Christian tradition, if we pay attention to the role of Mary Magdalene, it is fascinating to note that all four canonical Gospels — Matthew 28, Mark 16, Luke 24, John 20 — agree that women were the first to learn about Jesus’s missing body, and women were the first to proclaim the story of the Resurrection. Why the women? Because the men were in hiding behind closed doors! For this role, Mary Magdalene has been called the “Apostle to the Apostles.” So, one could ask, if a woman preached the first Easter sermon, how can one possibly be against the ordination of women?! (The answer is to stay in a patriarchal bubble in which all biblical interpretation is done by men and for men.)

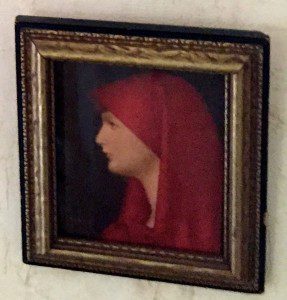

But the role of women in the Christian tradition could never been fully covered up or eliminated: “In Western Europe, over 190 shrines were dedicated to Mary Magdalene, and more than 600 of her relics venerated. In Reformation England, there were 170 churches bearing her name” (50). Indeed, on  the living room wall of my grandmother who was a lifelong Southern Baptists was a collection of three prominently placed pictures: two are traditional “Madonnas” of the Virgin Mary, one in all black for mourning, one is wearing the traditional blue associated with Mary. But the third — wearing bright red — is clearly a Magdalene. My grandmother inherited these pictures from two of her older sisters. To me, they are yet one more testimony to the search for the missing element of women’s experience and leadership in the Christian tradition, which thankfully is changing more rapidly in recent decades.

the living room wall of my grandmother who was a lifelong Southern Baptists was a collection of three prominently placed pictures: two are traditional “Madonnas” of the Virgin Mary, one in all black for mourning, one is wearing the traditional blue associated with Mary. But the third — wearing bright red — is clearly a Magdalene. My grandmother inherited these pictures from two of her older sisters. To me, they are yet one more testimony to the search for the missing element of women’s experience and leadership in the Christian tradition, which thankfully is changing more rapidly in recent decades.

But in reclaiming women’s experience in the Christian tradition, feminist scholars right warn against a naïve perspective that there was some perfect egalitarianism in the beginning of the Jesus tradition that was then corrupted by the patriarchy. Rather, scholars such as Schüssler-Fiorenza invite us to consider that there has always been an ongoing struggle for equality and community over against domination and control (199).

If that is the case, how should we adjudicate between all the incredibly diverse and conflicting claims that individuals and groups make about Jesus and the Christian tradition? Melanie Johnson-Debaufre, a student of Schüssler-Fiorenza, argues that the criteria for choosing should be a pragmatic one: if the way someone is teaching and practicing Christianity contributes toward the “liberation and dignity of all people,” then we should support it. Conversely, if the way someone is teaching and practicing Christianity leads to domination and control (especially of individual men over women or over minority groups), we should oppose it (200).

To use a Buddhist metaphor along these lines, arguably the greatest error in the Christian tradition has been “mistaking the finger pointing at the moon for the moon.” When we look at Jesus’s own life and teachings — as opposed to the ways he was deified by others after his death — we don’t see Jesus pointing to the importance of his own person or the significance of his future martyrdom. Rather, in the first chapter of the Gospel of Mark, the earliest of the canonical Gospels, we read, “Jesus came to Galilee, proclaiming the good news of God, and saying, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news’” (Mark 1:14-15). Note that the good news Jesus is proclaiming in his public ministry is not that he is going to die on the cross in a few years. Instead, he is pointing beyond himself to what he called the “kingdom of God” — or what we can call the “Beloved Community,” following The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. But far too often the Christian tradition has stumbled over the identity of Jesus or made an idol of the Bible — thereby confusing the pointing finger with the moon — when the most important point has never been either Jesus or the Bible, but rather how both Jesus and scripture point us away from ourselves and our narcissism and redirects us toward building the Beloved Community both then and now (201).

The reason I chose to write about “The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene” is to:

- refocus our attention away from all the debates about the identity of Jesus (who is ultimately just one individual male);

- remind us that salvation is much less about what anyone believes about what happened two thousand years and much more about whether you seek justice, kindness, and compassion here and now;

- turn our attention toward the building of a diverse Beloved Community that dares to transgress traditional boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, and class.

Reconsidering the Christian tradition from the perspective of Mary Magdalene challenges us to demand a spirituality that is worthy of our whole selves. And she — the “Apostle to the Apostles” on that first Easter morning — reminds us that the final truth of Easter turns on whether we will recommit ever anew to the hard, risky, but vital work of building the beloved community: of working each day within ourselves, in our intimate relationships, and in our communities for rebirth, renewal, and resurrection.

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles