Rest in peace, Father Luke Kot.

Rest in peace, Father Luke Kot.

Father Luke died tonight, at the age of 102.

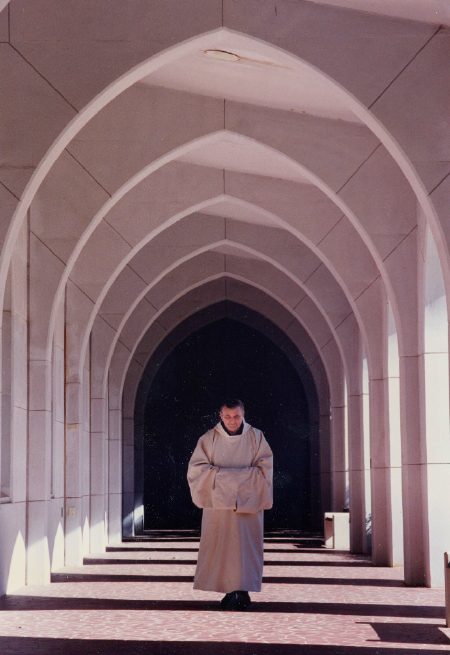

Father Luke was the last surviving of twenty Trappist monks who, almost seventy years ago, left Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky to take the midnight train to Georgia, arriving on a rainy day in Atlanta in March 1944 — the Feast of St. Benedict — to move into a makeshift cloister in a barn on an old plantation some thirty miles southeast of the city. From that humble beginning came the Monastery of Our Lady of the Holy Spirit, and from that rainy day on, this monastery in the deep south was Father Luke’s home.

For many years, Father Luke served the community as the monk who sewed — he made the habits, scapulars and cowls for the men in the community. In the early years of the monastery he served as the Abbot’s secretary, and in his later years as the unofficial historian of the community. Even after his hundredth birthday, he remained active working in the monastery’s welcome center, where he would make finger rosaries and greet visitors.

Five years ago I had the good fortune to interview Fr. Luke for an article that ran in the Georgia Bulletin, the Catholic newspaper for the Archdiocese of Atlanta. It was just a few months before he was to celebrate his 70th anniversary as a monk (he entered Gethsemani in 1938). As I interviewed him, it occurred to me that he would have known Thomas Merton, who entered Gethsemani in 1941, three years after Fr. Luke. So I asked him what he could recall about Merton.

“He was just another monk!” Father Luke said, matter-of-factly. Considering that Merton did not become famous until 1948 — several years after Father Luke moved to Georgia — his answer made perfect sense. Here was a man who knew Merton the monk, but who never really was exposed to Merton the celebrity.

Ironically, in his own way Fr. Luke became a celebrity, beginning in 2005 when Fr. Francis Xavier passed away, leaving Fr. Luke as the last surviving founder. His affability, sense of humor, obvious humility, and gifted ability as a storyteller made him popular among all who visited the monastery. His 100th birthday, in August 2011, was quite the event — with the monks throwing a huge party and a write-up in the Georgia Bulletin. The Lay Cistercians (of which I am a member) threw our own party for the centenarian, marking his birthday along with that of Fr. Anthony, a mere whippersnapper at 83, seventeen years his junior. Here is a video from that happy day.

Over the last year Father Luke had been markedly frail; a somber reminder that even the hardiest of bodies must eventually surrender to the silence of eternity. I’m tempted to say that it’s sad he didn’t live just ten more weeks, to see the 70th anniversary of the founding of the monastery. But that’s a silly way to look at things. Perhaps Fr. Luke decided that for the seventieth anniversary, it was high time he joined all the other founders and mark the occasion in heaven. And we who remain — the surviving monks, the Lay Cistercians and other friends of the monastery — will carry on without him, and we’ll miss him; we’ll miss his simplicity, his innocence, and his mischievous grin. But we’ll also give thanks to have known such a lovely, down-to-earth, holy man. Even if he was… well, just another monk.

Here’s the article I wrote in 2008 for which I interviewed Father Luke.

Stability Amidst Change

Georgia’s Trappist Monastery

Preserves Timeless Spiritual Values

When twenty-one monks traveled by train to Georgia in the spring of 1944 to establish a new Trappist monastery, none of them dreamed that their new home would someday sit on the edge of Atlanta’s urban sprawl. At that time, Honey Creek Plantation — the 2000 acre tract of land where the monks would settle — was a cotton field in the middle of farm country. Atlanta was over thirty miles away; the nearest town, Conyers, eight miles to the north. “The monastery was on a dirt road,” remarks Fr. Luke Kot, who at 97 is the only surviving monk of the original twenty.

Today that dirt road is Georgia Highway 212, and while some small farms remain, much of the land surrounding the Monastery of the Holy Spirit is dotted with single family homes. But as much as its surroundings have changed, the monastery itself, as part of a 1500-year-old Catholic tradition, embodies stability and serenity.

“Next to the family, monasticism is the longest standing institution in the history of humankind,” notes Dom Francis Michael Stiteler, the current abbot of the Monastery of the Holy Spirit. “No matter how far back you go, wherever you find civilization you will find men and women living at a distance from the mainstream community who are pursuing the Divine — the transcendent, the bigger questions.” Such intentional communities of the spirit cut across cultural, geographic and religious boundaries. Among Christians, the earliest monasteries date back to the fourth century, when communities began to form in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine. In the sixth century, St. Benedict wrote his Rule for Monks which became the guiding document for almost all monasteries in the western church. After 1500 years it continues to inspire monastics (both men and women) throughout the church, including the monks of Conyers.

“Originally almost all Christian monasticism emphasized silence and solitude and some form of separation from the world,” notes Dom Francis Michael. Monks were, after all, seekers yearning for the heart of God, and St. Benedict envisioned monasteries as “schools of the service of God,” where monks could support one another in their common desire to more perfectly follow Christ. Even in their most austere forms, monasteries were never intended as ways to escape the world. Over the course of Christian history, monks have contributed to the church and society, through hospitals, libraries, schools, and contributions to the farming economy of Europe.

While such service has always been a valuable part of Catholic culture, throughout the centuries some monasteries have sought new ways of being faithful to the oldest values of monasticism. In 1098 the Cistercian Order emerged, seeking to follow the Rule of Benedict as authentically as possible; further reforms in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries led to the Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance — the monastic order to which the Monastery of the Holy Spirit belongs.

In 1848 French monks came to America and founded the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky. Nearly a century later, twenty monastics left Kentucky for Georgia to establish a new community following an age-old tradition. “As soon as we arrived, we unpacked our bags, set up our altar, and began our daily prayers,” notes Fr. Luke. Almost 65 years later, the monks of Conyers are still praying every day. And like monks all over the world, they welcome visitors to their church, guesthouse, and grounds, whether for a few hours or a few days. Dom Francis Michael believes that “everyone has a monk, a searcher, in themselves. A monastery provides the locus for that primal desire to express itself and to be shared.”

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.