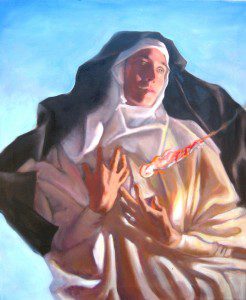

Today is the feast day of one of the lesser known of Cistercian blesseds (and medieval mystics), Beatrice of Nazareth, who lived ca. 1200-1268 CE.

Born in or around 1200 CE, Beatrice of Nazareth was the youngest child of a devout Flemish family; her father may have been a mason involved in the construction of three different monasteries. A devout child, after her mother’s death when she was 7 Beatrice lived for a year with Beguines (lay women who lived communally). Afterward she went to live with nuns, and even as a child began to engage in severe ascetical practices (fasting and self-denial). As a teen, her superiors sent her to a neighboring convent to learn the art of manuscript writing. At this time she met Ida of Nivelles, only a year older than Beatrice but already known to be a mystic. Forming a close bond with Ida, soon Beatrice received her own ecstatic vision — of the Trinity, the Heavenly Jerusalem, and choirs of angels. After the vision, Beatrice reacted with profound emotion: she sobbed when she realized her ecstasy had ended, but also felt such immense gratitude that she laughed out loud. But after a short period of happiness, she fell into a state her biographer called “the wound of sloth” leading to a sense of fatigue and inertia; Beatrice’s religious observance became slack for several months. After receiving a letter from Ida in which her friend encouraged her to take communion, Beatrice began to re-integrate herself into the religious observance of convent life. From here, the young girl (she was only sixteen at the time of her ecstasy) began to understand that the spiritual life was not about making demands of God; and that extreme acts of asceticism or self-denial could be harmful rather than sanctifying.

During her young adult years, Beatrice immersed herself in the ordinary life of a nun, studying scripture, striving to grow in virtue, and participating in the spiritual exercises of her community (such as the Daily Office and lectio divina). She struggled to cleanse herself of her sins, but came to see that penance or asceticism did more harm than good. She also tried to motivate her quest for holiness through giving thanks to God, and by seeking through the force of her own will to love — but naturally she discovered that these willful actions could not achieve the sanctity she desired. Distraught, Beatrice prayed to God for help — and in response, she realized that God wanted her to affirm her soul’s innate beauty. She realized that God gives all people natural virtues, in different measures to each soul. Seeing that her soul contained its own beauty, and that furthermore each person is unique, liberated Beatrice to follow the path of sanctity given to her alone by God — which is to say, to become holy by being true to her own unique gifts and virtues.

But this insight was not the culmination of Beatrice’s journey. After several years of relative peacefulness and stability in her life as a nun, another long season of depression and inner turmoil returned. She was beset by fear that she might lose her vocation or succumb to sinful thoughts and temptations. But during this “dark night”period, she received insight that even her struggles could be a gift — a way God could train her for greater holiness.

Her depressed state lasted for a number of years, but was punctuated by occasional visions or ecstasies. One time she heard God tell her that they would never be separated; another time she received a momentary vision of the Sacred Heart. But she also suffered physical torments in addition to her spiritual struggle, including fevers and physical pain (one theory holds that she may have suffered from recurrent malaria in addition to possible bipolar disorder). Her ecstasies continued, along with insight into how impossible it was to retain the intensity or beauty of her visions.

In 1231, Ida of Nivelles died, causing Beatrice much grief. Meanwhile, Beatrice had developed her own reputation as a mystic and holy woman, and struggled to ignore the adulation she received from others.

Eventually Beatrice was appointed the prioress of the Nazareth convent (In Belgium, not Israel), a community which subsequently joined the Cistercian Order. Little is known about this period of her life, but before her death at age 68 she composed her one written work which has survived to the present day — a brief mystical treatise, The Seven Manners of Loving. This meditation on the dynamics of how mortals respond to God in love offers a poetic and cyclical exploration of how love for God evolves over time.

Here, in summary form, are the seven manners of loving:

- Active longing for restoring the image and likeness of God, which proceeds out of love;

- Offering oneself to God;

- Suffering for God;

- Enjoying the splendor of God’s love;

- Accepting that love includes both ecstasy and agony;

- Resting confidently in God’s love; and finally,

- Contemplating the Divine Mystery of love, which paradoxically brings us back to an ever-deeper longing.

In this brief treatise (the English translation I read is only about 3700 words long, or about three times the length of this blog post), Beatrice has beautifully unpacked the rich dynamics of the process by which we may respond to God through love. Of course, God is love, so the love we offer to God is merely a return of the gift of love God has given to us. Over the course of the seven manners, the lover of God experiences a dialectic of enjoying God’s presence and suffering God’s apparent absence; of enjoying the beauty of love while also suffering the inevitable pain of love; but after reaching a place of acceptance, the dialectic merges into a nondual encounter with love, through an ordinary sense of rest, leading to a rich contemplation of love which bridges the gap between “earthly” and “heavenly” — even while it continues to inspire a sense of longing (it reminds me of Bernard of Clairvaux, who suggested that the more we received Divine Love, the greater our longing for it grows).

I think it would be a mistake to assume that Beatrice’s map of the seven manners of loving is universally applicable — in other words, just because this is how the dance between divine and human love took place in the life of Beatrice, doesn’t mean that everyone will necessarily embody these seven manners in this precise sequence. I think it’s important, as a general rule, not to universalize the teachings of the mystics and assume that our journey into the heart of God must look just like theirs (which is a good thing, since the mystics often contradict each other). But with that caveat in mind, I still find Beatrice’s map of love to be quite compelling, and I suspect most people who long for God’s love (which, after all, is manner #1) might recognize many or even all of these seven dimensions of love. At the very least, this is great material for meditation.

To learn more about Beatrice, you can download two translations of her work here and here, or read The Life of Beatrice of Nazareth, which includes translations of both the Latin and vernacular texts of The Seven Manners of Loving.

My source for this blog post is Jerome Kroll & Roger de Ganck’s article “Beatrice of Nazareth: Psychiatric Perspectives on a Medieval Mystic,” Cistercian Studies Quarterly, Vol. XXIV 1989:4, pp. 301-323.

Disclosure: If you follow the link of the book mentioned in this article to Amazon.com, and purchase it or some other item, I receive a small commission. Thank you for doing so: it’s the easiest way you can support this blog.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.