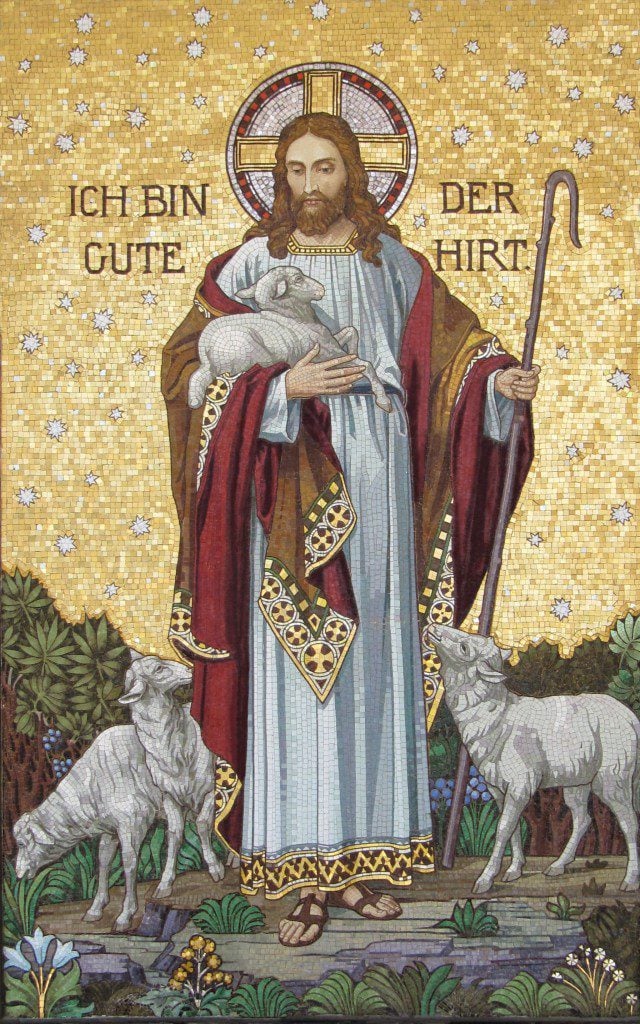

A Meditation for Good Shepherd Sunday (May 7, 2017)

So I suppose the obvious topic for a reflection on Good Shepherd Sunday is… well… sheep!

But I am not a farmer, I have never lived on a farm, in fact I don’t know that I have ever lived particularly near a farm. I’m a vegetarian, so I don’t eat mutton. Really, my knowledge of sheep pretty much begins and ends with a couple of nice wool sweaters that I own. And in Georgia, you don’t even need to wear those very often!

But I’m not just trying to make a few feeble jokes here. What I’d like to do is talk about a challenge that many of us face more often than we may care to admit: sometimes, the lessons that come to us from the treasury of the Bible may very well speak to us in a language that we don’t readily understand.

I’m not just talking about Hebrew, Greek, or Aramaic; after all, you can take classes at your local seminary to learn the Biblical languages, or you can be like me, and master them just enough to be dangerous. No, it’s more than just an unfamiliar tongue that we must contend with. The stories, and poetry, and wisdom sayings, and other writings that comprise our Holy Bible come to us from a culture, and a time, that is very much unlike our own.

And yet, we sing, “Alleluia, Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. Alleluia, alleluia.” If we believe, and I certainly do, that the Bible has the words of eternal life, then what are we to do when we call Jesus the Good Shepherd, but we don’t even know sheep? Or Jesus tells us his yoke is easy, but we’ve never worked with a real yoke?

But there’s more at stake here than the colorful imagery from the gospels. What do we do with the Apostle Paul, whom we call the first great theologian, and yet he tells us that gay people deserve to die, or that wives should submit to their husbands?

What do we do when Jesus curses the fig tree? Or praises the unjust steward? Or tells us that camels will have an easier time getting through the eye of a needle than a rich person trying to get into heaven?

You know, I don’t like to think about it, but my very-middle-class-American income makes me, by global standards, actually a pretty wealthy guy.

And what scares me even more is this: how many ways do I miss the point of scripture, when I’m not even aware that I’m doing so? In other words, how many ways, over the centuries, have we lost or changed certain ways of thinking, certain ways of understanding kinship and hospitality and time, insights into eternity and into compassion and even into the human heart and mind, that have left certain passages in scripture just obscure? Difficult to understand? Or worse yet, easy to misunderstand?

So how do we relate to the strangeness, the challenge, the mystery of scripture?

I have three thoughts. And interestingly enough, they all come from… surprise! Today’s lessons.

The lesson from the Acts of the Apostles teaches us that community really matters in the Christian life. We can’t do it alone. We can’t be saved all by ourselves, we can’t become holy all by ourselves, we can’t live a good and happy and fulfilling life all by ourselves. It simply isn’t possible. In fact, Acts makes some pretty radical statements about being non-attached to our resources, living in an economy based on generosity and sharing.

Pretty radical stuff. What would our world look like, if we measured wealth not by how much we have accumulated, but by how much we give away? It’s a great question… but for now, let’s just focus on the importance of community. And what did the community do: they taught one another, they enjoyed one another’s companionship, they prayed together, and they worshiped together.

Luke, the author of Acts, doesn’t talk about them going to seminary, or getting advanced degrees in theology! And I don’t mean to knock the importance of a good education. But I think we can learn from this passage not only that scripture needs to be interpreted in community, but that such interpretation can only happen in the context of much prayer and worship.

If you want to know how to read the scripture, first learn how to pray the scripture.

And we learn how to pray the scripture — and to interpret the text — together. In community.

Our second lesson, from Saint Peter, sounds suspiciously like the Beatitudes, which has been the topic of our retreat this weekend. Peter mentions sheep and shepherds at the end of this lesson, which is probably why it was chosen for today’s readings. But really, I think we find the true heart of this lesson in how “Beatitudinal” it is.

If you endure when you do right and suffer for it, you have God’s approval. For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you should follow in his steps.

I don’t know about you, but to me that sure sounds like

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. “Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely[a] on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

Isn’t it fascinating how Jesus pivots here? He goes from speaking abstractly, in the third person: “Blessed are THOSE” — and makes it personal, speaking directly to his audience: “Blessed are YOU.” Because Jesus is all about relationship, and what a lot of us fail to realize is that Jesus wants a relationship with you… and you… and you… and me, and you… with all of us. And that’s a personal relationship. It cannot be systematized, or codified.

But back to the lesson. What does Saint Peter teach us about how to dance with the mystery of Scripture? I think the message here is very simply this: that the key to receiving the wisdom of scripture lies not so much in how much we understand, but in how we choose to live. We can’t think our way into heaven. But in our hearts, we can receive the love which has already promised to carry us there.

And that leads to our third lesson, from the Gospel of John, where Jesus compares himself to the gate through which the sheep move to safety. He doesn’t call himself the Good Shepherd in this Gospel reading, but if you kept on reading the Gospel of John, he says so in the very next verse. “I am the Good Shepherd.” Trust me: today is still “Good Shepherd Sunday.” At least that’s what Wikipedia says.

So I don’t know much about sheep — or shepherds, or gates that lead to sheep-pens for that matter — but here’s what I see in this Gospel reading. That at the end of the day, what really makes us Christian is not thinking all the right thoughts — even though sound doctrine is of course important — or even behaving all the right ways — after all, Jesus remarked that the prostitutes and the tax collectors will be leading this parade.

Yes, holiness is important, just like sound doctrine is important — but most important of all is faith, and faith is a relationship. The sheep obey Jesus not because they’re stupid, not because they’ve been trained the right way, but because they know his voice. They trust him. Their faith is based on the relationship.

And it’s in that context of relationship that Jesus is the gate, the gate that opens to new life. We walk through that gate, even though we don’t have it all figured out, because we trust in Jesus. We know he is worth trusting, even when we’re not sure where the path is heading.

This reminds me of a wonderful prayer by Thomas Merton, which many of you will already know. And if you don’t know this prayer, listen to it, because it is filled with wisdom.

MY LORD GOD, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think that I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road though I may know nothing about it. Therefore will I trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.

In the end we have to acknowledge that even if you master all the Biblical languages, and become an expert on the philosophy and culture and beliefs and values of the Biblical world, and you get five PhDs in sacred theology and scripture studies and hermeneutics and heuristics and so forth and whatnot — guess what? Scripture will still be a mystery to you. It had better be! It had better be a mystery to you, because the minute it stops being a mystery to you is the minute when you think you no longer need God. And may God forbid that any of us ever reach that moment.

Yes, my friends, at the end of the day, the mystery, the incomprehensibility, the strangeness of scripture, is a profound gift to us all. Because we are left with saying “I don’t know.” We are left with saying “I believe, help my unbelief.” We are left with saying “I’m not much smarter than a farm animal.” “I sure need God to lead me.” Just like a sheep.

Amen.

N.B. The above homily was delivered on Sunday, May 7, 2017 at the annual retreat for the Worker Sisters and Brothers of the Holy Spirit, an Episcopal/ecumenical religious order. Here are the lessons for this homily:

Acts 2:42-47

Psalm 23

1 Peter 2:19-25

John 10:1-10

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.