Before I launch into a series of new posts tomorrow, here is a local copy of the post I contributed in July for the Patheos Future of Faith series. Future posts will often refer back to themes from this one.

If the church is to survive and thrive in the United States, we have got to face facts.

“Facing facts” here does not involve a gloomy recap of survey data showing increasing rates of religious “nones” without any church affiliation, especially among the Millennial generation born since 1981. Such gloom is common enough: identify the problem (declining numbers), diagnose the cause (disconnection with Millennials), and prescribe a solution (more authenticity or stricter orthodoxy).

No, first among the facts to face is that we humans are bad at facing facts. We are afflicted by a menagerie of cognitive biases that blind us to our ignorance and dispose us to choose facts we like. Actor-observer bias, confirmation bias, anddefensive attribution bias reinforce our tendency to blame accidents on the character flaws of others, while attributing our own role in “accidents” to circumstances rather than our own character flaws. We prefer heuristic simplifications of complex reality so we can avoid the hard work of understanding.

Jesus perceived such bias in his disciples’ response to a famous accident (Luke 13:4). Later, he warned them: “You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye.” (Matthew 7:5, NIV)

Recommendation: Help your church face facts. Ask polite, difficult questions, such as: “Have we considered other explanations for our problems? Are we looking at years and city blocks when we should be looking at decades and cities? Can we change the things we plan to change?”

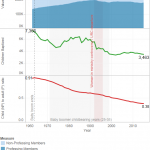

A second fact to face is the church is not exempted from demographics. We can’t blame macroscopic trends like fertility rates, so we overlook them. Birth rates, driven by education and income, can account for 75% of the last century’s changes in religious affiliation.

Years ago, a faction blamed my congregation’s membership decline on our pastor’s preaching. But evidence pointed to long-term suburban emigration and short-run resources skewed toward older members. Congregations can’t learn from demographic analysis if we resist explanations that don’t blame someone. Allocating resources to children and young adults is not “selling out to youth culture.” Otherwise, there will be no volunteers to care for our elders.

Recommendation: Keep a record of every congregant’s birthday. Make a simplehistogram. If the age distribution is skewed, take action. Read Sustainable Youth Ministry by Mark DeVries together. Discuss, implement, and review annually.

A third fact to face: we don’t like good news. We are loss averse, preferring to limit losses rather than increase gains. We are riveted by crises and underwhelmed by peacefulness. We overestimate rates of crime and disease and don’t retain facts about how things are getting better. Many wring hands over religious “nones,” but few rejoice in the projection that evangelicals would gain the most new adherents if current trends continue due to higher conversion and retention rates.

The church should resist this bias fiercely. Jesus was famous for celebrating (Matthew 9:14-16)—infamous to the Pharisees, to whom he responded with three parables about celebrations that contrast humans finding lost things with heaven’s joy in finding lostpeople (Luke 15).

Recommendation: Resist the idea that God prefers tearful prayer meetings to chatty potlucks. Celebrating meals together is a faithful, biblical act (Acts 2:42-47). Inviting sinners is Christlike!

Finally, we have to face the fact that many of our perceived problems now are partly due to our faith’s long-term successes. We are disgusted by sins all around us because perversions once reserved to aristocrats have been democratized, right alongside virtues like literacy and freedom of worship. Democratization has deep roots in Protestant forms of congregational governance, the “priesthood of all believers,” and the confidence that “God does not show favoritism” (Acts 10:34, NIV). Taking responsibility for democratization is not triumphalist American civil religion. As Robert Woodberry’s magisterial work shows, Christian missions have had a global democratizing effect over centuries.

Pastors are less respected today partly because their congregations are better educated—and Christians promoted much education (Pastors in Transition, page 5). Church programs and events face fierce competition for membership and donations from mass electronic media and 1.5 million charitable nonprofits, most of which didn’t exist just 75 years ago—and Christians founded many nonprofits. We have to adapt to the consequences of our movement’s actions.

Recommendation: Let’s transform our congregations from “anchors” that grimly compete for congregants’ scarce time and talents into “launching pads” that generously celebrate the varieties of Christian vocation. Pastors should be models of work-life balance, relaxed, wise, welcome visitors to the places where congregants work, volunteer, play, rest, and heal. Church information systems should embrace social networking, manifesting new local incarnations of the Body of Christ in worship, service, grief, and celebration.