One of the pillars of Enlightenment, scientific, and New Atheist (not to be confused with the other two) lore is the tall tale that Christianity came like some prehistoric meteor and wiped out the advanced science of the ancients.

Hypatia of Alexandria is frequently used in this narrative as martyred by bloodthirsty ancient Christian fundamentalists. On this story, the fog of ignorance spread by the Roman Catholic Bible Belt’s dogma-machine was so powerful that it took science over a millennium to recover its former greatness during the late Renaissance.

It’s often forgotten that most of the earliest scientists were either religious (priests) or religious people (believing laymen). Incongruous details like that are not important. Keep in mind this is a myth.

The story begins to fall apart when you take a look at the ancient intellectual martyr par excellence: Socrates. Granted, the Christians were around to induce him into boozing himself to death, but . . . details, schmetails.

Anyway, you might remember that as Socrates is sitting there in the Phaedo, waiting to swig the hemlock, he recounts his progression through various methods at attaining the truth. There’s something like a scientific method’s process of elimination going on there. Socrates experiments with the hypothesis that some ancient discipline will bring him to enlightenment about life, only to see the discipline fail in practice. The ancient natural sciences are one of the disciplines he attempts, but it too is a failure. Actually, it is the first thing he tries and it fails. Why? Because changing natural phenomena provide him with no ground for understanding his life. They are a distraction at best.

Such examples multiply throughout the ancient world. You won’t find an exception in Plato’s other writings, nor even in the pseudo-natural-scientist Aristotle. The Socrates example is representative of the dismissive attitude of the ancient Greeks and Romans toward the vestiges of what we might consider the natural sciences. However, the story is a little bit more complicated than that.

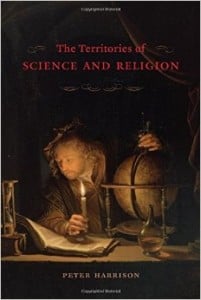

The complexities of ancient attitudes toward our cherished practices, which we assume had to be valued by all reasonable ages, can be found admirably laid out in Peter Harrison’s invaluable new tome, The Territories of Science and Religion. Harrison’s book deserves a place right next to all your most important critiques of modernity and genealogies of secularization.

I’ll show you why by first letting Harrison set down the myth under discussion on the next page of this post: