St. Augustine’s Press is probably familiar to you as a publisher of both new books, and reprints of old favorites like Camus’s Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism.

This fall brings another fine reprint title, yet another old French favorite. The novel in question has been out of print for so long that it’s skipped a generation or two of awareness.

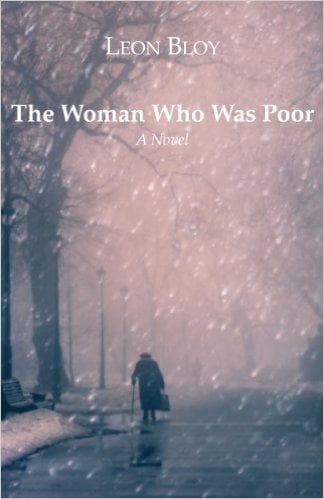

I’m talking about Leon Bloy’s immensely influential novel The Woman Who Was Poor. Its influence alone makes it the reprint of the year.

If the name sounds vaguely familiar it’s because Bloy is the person who dragged the Maritains into the Church (not Martians, but the whole Jazz Age Catholic generation), is quoted in Graham Greene’s epigram to The End of the Affair, Jorge-Louis Borges also put him in his essential literary pantheon of unorthodox (style-wise) writers, and so on.

More recently you saw his name dropped by Fabrice Hadjadj in an interview I translated for Ethika Politika and . . . by Pope Francis.

Yes, Bloy is everywhere! You just don’t know it.

If still you have no idea what I’m talking about, this is how the publisher summarizes The Woman Who Was Poor:

Written in the 1890s, this novel has had an immeasurable effect on all European Catholic writing since. It is an extraordinary book, powerful in the manner of dos Passos, yet spiritual in the manner of the Bible.

It is the story of a woman abysmally poor, brutally treated and also exploited by her parents, living in the gutters of Paris, yet retaining the spiritual outlook and the purity of a saint. We are spared no brutality, yet there are scenes of the most tender beauty . . .

. . . The novel ends with those famous words of extraordinary optimism: “There is only one misery . . . not to be saints.”

Not bad, eh? Here’s a sample passage from the novel that really caught my eye:

Without Barabbas the Redemption would not have been. God would not have been worthy to create the world had He forgotten to evoke from the void that host of riffraff who crucified Him.

If that seems like an outrage, then you ought to know the book starts out with the line, “The place stinks of God.”

It’s all downhill from there.

Bloy’s style falls under the rubric of what I call Rabelaisian Catholicism, which you can see on display in Kenneth L. Woodward’s recent guest post.

I’m a man who’s still poor, so please consider clicking on the PayPal donation button on my homepage.