A very perceptive piece by Damon Linker about the recent referendum in the United Kingdom:

http://theweek.com/articles/632380/how-brexit-shattered-progressives-dearest-illusions

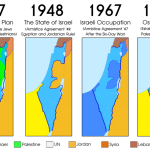

I was struck the other day by the British journalist David Goodhart’s distinction in the debate over Britain’s relationship to the European Union — which I saw cited here — between what he called “somewhere people” and “nowhere people.” By those terms, he’s referring to residents of the UK who feel deeply English, profoundly connected to the traditions of their little island, its history, its culture, its villages, its peculiar traditions and institutions, as opposed to those who feel themselves fundamentally “European.” (As my Scottish seat mate — not coincidentally, a backer of the “Remain” side — approvingly put it to me the other day on our flight from Sweden into Edinburgh, younger people today feel no more reluctance to move from Scotland to Sweden, where his son has lived with a Swedish girlfriend for the past eight years and worked for a Swedish company, or to Germany, where his daughter works, than Americans feel about moving from Oregon to Washington, or from New Jersey to Pennsylvania.)

I like Goodhart’s distinction, and, although I’ve only seen it referred to at second hand, I think it very insightful. It seems to me related, too, in subtle ways, to the decline in the importance of denominationalism in American religion; the relative weakness of the American family, the decline in the marriage rate, high rates of divorce, and the increasing age of first marriages; debates about same-sex relationships and the redefinition of marriage; the rise of the behemoth state in Washington (and in Brussels); and so forth.

I think of this famous passage from the Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke (1729-1797), who is often considered the father of conservatism in the English-speaking world, which occurs in his Reflections on the Revolution in France:

“To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country and to mankind.”

I’ve always been wary of people who claim to love “humanity”; too many of them seem to have real difficulty treating their wives, children, landladies, and neighbors even minimally well. (See Paul Johnson’s book Intellectuals for a parade of notable examples. And many others could be mentioned.)

I’ve always been delighted to find local authors wherever I go. Writers who haven’t bowed the knee to Manhattan. I always seek out local restaurants and specialties, order local favorites.

Years ago, I read about a tee shirt worn by Larry McMurtry, a Pulitzer-Prize-winning novelist and essayist based in Texas, which read “Important Regional Writer.” That’s how the New York Times had described him. I liked the implicit thumbing of his nose against the sheer unconscious arrogance of that “compliment.” Why is Texas a “region,” while New York City apparently isn’t? Is the Pulitzer Prize not a national award? Is Jane Austen a merely regional writer because her novels tend to involve only small domestic stories in relatively rural areas? Søren Kierkegaard lived in the tiny country of Denmark, and wrote not in French or German or English or Latin but in the somewhat marginal language of Danish. But he treats the very biggest and most fundamental of issues.

In this regard, I came across a nice passage a couple of days ago from Hugh Walpole’s 1930 novel Rogue Herries:

“‘How shall I like this place? It is cut off from the world.’ There was an odd note of scorn in the little man’s voice as he answered. ‘It is the world, sir. Here within these hills, in this space of ground, is all the world . . . in every village through which I have passed since then I have found the whole world — all anger and vanity and covetousness and lust, yes, and all charity, goodness, and sweetness of soul. But most of all here in this valley, I have found the whole world . . . You will find everything here, sir. God and the devil both walk in these fields.'”

My inclination to “localism” is one of the reasons, I suppose, that I enjoy the writing of Wendell Berry and Victor Davis Hanson and the late Russell Kirk and that it’s deeply satisfying for me to be here in the Lake District, where so many fine authors have so wonderfully expressed their sense of attachment to particular places. (Years ago, I was delighted when a well-received collection of work by Montana writers appeared, entitled The Last Best Place. And, even before that, I was fascinated to learn about the group of prominent writers in the 1930s, centered in Nashville, who’ve come to be known as the “Southern Agrarians.”) I strongly believe in supporting local theater (e.g., our annual tradition of attending the Utah Shakespeare Festival in Cedar City and our attendance at the Utah Festival Opera in Logan, and our season tickets at both Hale theaters). I’m irritated that plays haven’t really arrived, in the view of some — even if they’ve already played at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles or the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis — until they come to the (often quite unimpressive) theaters of Broadway.

I recall talking with a friend in Cairo many years ago who had been born and raised in New York City before he ventured off to do his undergraduate schooling at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and who was then working on a doctorate at Princeton (back up nearly to New York City). He told me of the one trip he had made Out West, to visit a girlfriend in Berkeley. As he flew over the United States, he told me, he realized that there was really “nothing” between the East Coast and the West Coast. It was so absurdly like the famous New Yorker cover by Saul Sternberg that I could barely keep from laughing. “You’re right,” I responded. “There’s really nothing — apart from Pittsburgh, Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Atlanta, Minneapolis/St. Paul, Denver, Salt Lake City, and a huge host of similar nowheres.”

I’m deeply committed to federalism for related reasons (but also because it’s clearly the Constitution’s plan), to the idea that the states shouldn’t be viewed merely as administrative departments of the national government in Washington DC. (It’s to this extent, and to this extent pretty much alone, that I can feel some ideological sympathy for the Confederacy: Great man though he was, I still don’t understand Lincoln’s insistence that states could not secede from the Union. If they came together to form it in the first place, why did they not have the right of secession?) I admire the Swiss attachment to their cantons, and their relative lack of interest in their federal government, as well as their disinclination to join the European Union in the first place.

These are, of course, very big issues, and I’m just skipping along the surface of them. I need to head out into the Lake District!

A few words, by the way, about Damon Linker — his own — from an interview that he gave in 2015:

“I was raised as a secular Jew in New York City. (No religious education at all, no Bar Mitzvah, etc.) In my undergraduate and graduate education, I learned a lot about Christian theology and always found it impressive as a system of ideas, though I never entertained the thought of converting. That began to change when I taught at Brigham Young University for two years in the late 1990s. I found the Mormon students and faculty there to be extremely impressive — morally and intellectually serious. When I left the university (my non-tenured visiting position came to an end), I felt a loss, like something spiritual had been stirred up inside me that now lacked an outlet. I looked into my native Judaism, but by that point it seemed more foreign to me than Christianity, and especially Catholicism. (My wife is a cradle Catholic.) So I somewhat impulsively decided to convert. I was received into the church during the Easter Vigil Mass in 2001 at lovely St. Mary’s in New Haven, CT. (The long, involved homilies by the Dominicans at that parish spoiled me. I’ve never encountered anything remotely that engaging in the years since.)”

His relationship with Catholicism, though, is . . . complex: “I’m staying in Rome for now. If the church is a mansion, you’ll find me in the upstairs hall linen closet. That’s where they keep the tortured former atheist-Jewish converts.” (This is for reasons, I might add, that would make conversion to Mormonism problematic and unlikely for him.)

Posted from Brockwood Hall, Cumbria, England