(Wikimedia Commons)

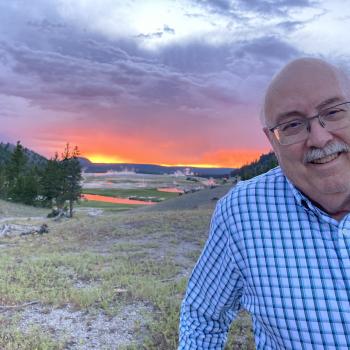

Five years ago this morning, I received the shocking and utterly unexpected news that my brother — strictly speaking, my half-brother — my only sibling, to whom I was very close, had died.

I was devastated. I still think of him, and I still miss him. Every day.

I’ve made it my practice, on this blog, to post something about him (typically, as here, my hastily composed and inadequate remarks at his funeral in South Pasadena, California) for his birthday and for the anniversary of his passing. Others may or, much more likely, may not care. But, frankly, doing this for my brother, and for my parents, and now for my eldest granddaughter — in memory of them, and out of love for them, and out of continuing grief for them — is one of the reasons I bother with the blog in the first place.

Here, below, is my funeral tribute, given in late March 2012:

(d. 23 March 2012)

I’ve been tinkering with a book project—with several book projects, actually—for a number of years now.

I never told Kenneth this, but my plan was to dedicate the first of them to “Kenneth D. Walters, best of brothers.”

It sometimes occurred to me, knowing the health history of his biological father, that if I didn’t hurry and get the book finished, I might someday be too late. But he seemed to be in pretty good health.

Now, though, I am too late.

And I’m so very, very sorry.

I wanted to say it to him. I wanted him to know.

Because he was the best of brothers to me. Generous, unfailingly supportive, probably my most enthusiastic fan.

The years likely stretching out before me seem, at the moment, bleak and desolate without his remarkable generosity and his never-failing enthusiasm for whatever I was doing. Sometimes, he would join me from California when I was lecturing in Missouri, North Carolina, or wherever, just to be supportive.

Several years ago, he attended a lecture of mine at BYU Education Week, in the Wilkinson Center Ballroom. The audience was very large, and a mass of people crowded around afterwards with questions and comments. But the next lecturer needed to set up, and we were encroaching on his time.

“Danny!” Kenneth called out, addressing me as only he, my older brother, and my mother and a handful of derisive Internet critics ever have since roughly my fifth birthday. “We need to go!”

“You dare to call him ‘Danny’?” responded an incredulous lady standing beside him, far more concerned about the speaker’s status and dignity than I’ve ever been.

He thought that was hilarious.

How dearly I would love to hear him call me “Danny”—or anything else—right now.

I love him more than I’m capable of writing or saying.

I’m a pretty unemotional person, usually. But I wrote this with aching eyes, tears, and sobs. It will be a minor miracle if I can deliver it at all well. For your sake, as well as for mine, I’ve prayed that I can.

He was ten years older than I am, and, strictly speaking, not my full brother but a half-brother. We didn’t even share the same last name.

But we never, ever, thought of ourselves as half-brothers. To my father’s eternal credit, he never made any distinction between us on that score, and neither did we.

Some of my earliest memories involve rough-housing with my older brother. Once, he lost track of how much younger and smaller I was, and I got hurt just a bit. He was almost inconsolable.

He was playful. One night, he was babysitting me and decided to watch the original movie of King Kong. It terrified me, but he held my hands so that I couldn’t cover my eyes and I was apparently too stupid to just close them.

I went, sometimes, to see him play Church softball. He was my hero, and he could hit the long ball. I thought of him as my own Frank Howard, a home-run hitting outfielder who was playing with the Dodgers at the time.

Another time, when he was a student at BYU and I was still roughly junior high school age, he sent me a box from Provo. I was excited to discover what it was, and reached my hand into the packing material to extract my prize. What I touched, though, felt very strange and worrisome. He had sent me a small sand shark for dissection, reeking of formaldehyde. It was, I think, part joke and part serious effort to give his little brother a really interesting experience.

Kenneth was as practically competent as I am a dreamer and impractical. We’re very different in many respects. So I was surprised when he told me, once, that his favorite college class had been a course on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. For years, he’s been a faithful attendee at the Utah Shakespearean Festival, often displeased when there was, in his view, too much modern stuff and too little Shakespeare. And, over the years, he became, thanks to Sandra’s passion for it, interested in the Shakespearean authorship question—inclining toward Edward de Vere, the seventeenth earl of Oxford. (He even adopted De Vere’s coat of arms as the symbol of the family construction business.) My wife and I even got the chance, once, to attend a seminar on that issue with them in Portland.

My father didn’t join the Church until 1972, so it was Kenneth who ordained me to the Melchizedek Priesthood, and he and Sandra, along with John and Diane Ziebarth, took me to the temple for the first time. In fact, we made a little temple tour of Utah right afterwards, in a time when there were only four temples in the whole state. When I was ordained a bishop a few years ago, Kenneth flew up to Utah, without telling me that he was coming, to be there for my announcement to the congregation and for my ordination.

The day Kenneth died, I was lost. I was supposed to speak in an academic conference that afternoon, but I bowed out. I just couldn’t have done it. The paper held no interest for me at all. Instead, Debbie and I went to the temple.

There, I saw lots and lots of older, white-haired people, both among the temple workers and the temple patrons. Not a surprise, of course. I couldn’t help, though, but feel some resentment at the injustice of it all: My brother didn’t even get to reach seventy. I had looked forward to at least five or ten more years of shared trips and lengthy phone calls. I know that time heals, but, honestly—even though we only got together a few times each year and only spoke every few weeks—the time I have left, if it’s as long as the actuarial tables predict, seems right now to stretch before me like something of an infinite and barren wasteland. I already miss him terribly. We had plans.

And yet, and yet . . . He died in a manner that most would envy, when it comes down to that. As Lord Tennyson’s poem puts it, “God’s finger touched him, and he slept.” No long debilitating illness, no loss of faculties. Its suddenness makes his passing all the more painful to us, but there was mercy in it.

Why did he have to go so soon, when he was still so vigorous? I don’t know. As Nephi expressed it, “I know that [God] loveth his children; nevertheless, I do not know the meaning of all things.”

I’m a really, really serious political conservative, and I owe a great deal of the credit (or blame) for that to my brother. He may have been the person who introduced me to William F. Buckley, and to Buckley’s National Review magazine, to which I’ve subscribed with very few interruptions (when I was out of the country) since I was about fourteen.

I like to brag, somewhat mysteriously, to some of my conservative friends that I voted for Barry Goldwater back in 1964, when I was eleven. And I really did. Kenneth took me into the polling booth with him, and allowed me to pull the lever for Senator Goldwater.

For years, we’ve traveled together. On both American coasts, in South America, Europe, even to Tombstone Days in Arizona. (Kenneth loved Tombstone Days. He had even bought himself a “duster,” the kind of long, loose coat that cowboys used to wear. I suppose that hearkened back to a time before I was even born, when he was very small and, my mother once told me, they had to hurry back from any trip they were on so that Kenneth could get into his black “Hopalong Cassidy” outfit, strap on his two white-handled toy revolvers, and plant himself in front of the television to watch Hopalong battle the bad guys.)

When I was still in high school, Kenneth and Sandra took me on a trip up to Alberta, over to British Columbia, and down the Pacific coast of the United States. I fell in love with places (like the Olympic Peninsula in Washington) that are still among my favorites to this day.

After some years where we had both been too busy with our own families and obligations, we had begun to travel together again, and I looked forward very much to these trips.

After years of trying and after several attempts that fell through at almost the last minute, I got to introduce him to my beloved Alps. And then, because he loved that trip so much, we got to go with him a second time.

A couple of years ago, at the end of our last trip to the Alps, he helped me to wrestle with and defeat a would-be pickpocket on the Milan Metro. I have a finger on my right hand that remains slightly but permanently bent from that encounter. Every time I look at it, I think of my brother.

My son Stephen has tastes in music that are far different from my brother’s love for Elvis and the Oak Ridge Boys. But Kenneth once volunteered to host him in California. He picked Stephen up, took him dinner, then took him out to The Jazz Bakery in West Los Angeles. They spent what was for Kenneth, I’m sure, a very long Friday evening listening to multiple sets of music that must have been excruciating to my brother. Stephen was ecstatic, though. Kenneth even secretly taped the performance, because he knew that Stephen would enjoy it so much. And, the next morning, when he was taking Stephen to the airport, my brother took him to Tower Records, where he could buy music that he couldn’t, in those days, get in Utah. Kenneth did this out of love for me and my family. I wish I had returned that love more openly and plainly. To say it now, with mere words, is scarcely adequate.

On another occasion, he and Sandra took us to an all-day Saturday blues festival in Long Beach. When I was very young, he took me and my friends to a Rolling Stones concert. It was mostly teenage girls screaming; we could scarcely hear the band, and I can’t imagine that he enjoyed it much. But he took us, because that’s the kind of brother he was. It’s the kind of husband he was, too. He laughed for years about being the only white guy in a huge audience—at, I think, the Long Beach Sports Arena—when he took his rhythm-and-blues loving blonde wife to a James Brown concert

I can’t believe he’s gone.

Speaking of Elvis: Several years ago, when Stephen and I were driving with my eldest son out to his Navy posting in Charleston, South Carolina, we stopped off by Graceland, in Memphis, Tennessee. For some reason, I’m absolutely impervious to Elvis. But I couldn’t resist calling Kenneth from Lonely Street, just in front of Heartbreak Hotel—a place that, I joked, surely had to rank in his mind as one of the most sacred places on the planet.

Kenneth was a gun enthusiast. He bought me an assault rifle. When he asked me how big a clip I wanted, I told him that I didn’t know. How many people are there, I asked, at the average post office or McDonald’s? I confess that I’ve only fired it once, when he came up and took me out to shoot it.

His generosity was stunning.

It took me a while to finish my dissertation, since I’d come up to teach at BYU and had very little time to work on it and nobody within six hundred miles who knew anything about my very obscure topic. He kept telling me that I needed to hurry, because he had a gift for me. And he did. It was a burgundy-colored 1971 Porsche 911 “Targa” that he had bought from a plastic surgeon friend of his. I had once commented that I loved Porsches, and he had never forgotten. So, when I finished my doctorate, I drove it up to Utah from California.

We were going to spend time with him up at the home he’s been building in Sandpoint, Idaho. But that won’t happen now. We were booked on a cruise with him around the British Isles in June. But that won’t happen now.

I was delighted at those opportunities because, as I’ve said, I knew the history of his biological father, and worried that such chances would come to a premature end. Now they have.

This has been harder for me than the passing of my parents. They were old. They had suffered. They were ready to go, and it was time. Kenneth’s passing came much too soon for me and for others.

I share with you, mostly as comfort for me, a true story that my friend and former neighbor Ken McCarty shared with me. Ken has been an associate at Brigham Young University and in church callings, and I write this with permission from him and his wife, Debbie.

Their daughter Sarah died in 1997, after a lengthy and difficult struggle with cystic fibrosis. She was just thirteen. She had, though, lived an extraordinarily full life in that short time.

In 1993, when she was roughly nine, Ken and Debbie took her on a cruise along the Volga River in Russia. Just before they left, Sarah’s friend Kerie Waters came to visit and to bring Sarah several balloons.

Kerie, 32, wore a headband to conceal the aftereffects of chemotherapy. She had been diagnosed only a few months before with terminal melanoma, a skin cancer, and their fatal illnesses had forged a special bond between her and the McCartys’ daughter. It was, as Debbie and Ken recalled, a tender goodbye.

One night, about two weeks into the trip, Sarah burst into her parents’ cabin, sobbing uncontrollably.

“I held her little shaking body,” Ken remembers, “and asked her what was the matter. When she finally caught her breath, she said, ‘Dad, Kerie has died.'” Ken was shocked — they had had little if any contact with home in those essentially pre-Internet days — and asked Sarah what had happened.

“I was kneeling by my bed, saying my prayers,” Sarah replied. “Suddenly I felt someone standing behind me. Then I realized it was Kerie. Kerie was in my room.”

“What did Kerie say?”

Sarah responded that Kerie hadn’t talked out loud, explaining that, in her heart, she could hear Kerie say that she had come to tell Sarah not to be afraid to die, that dying wasn’t scary, it was beautiful.

“Kerie didn’t want me to worry about her; she wanted me to know that she was very happy in heaven.”

Shortly after returning home, says Ken, he called Kerie’s father, Wes Waters, and found out that Kerie had indeed died — around thirty minutes before Sarah’s experience in Russia.

But that’s not the end of this story.

On the April morning when Sarah herself passed away, her parents decided to wait until around 8:30 a.m. before they began the mournful task of calling to notify family and friends. But at approximately 8 AM, their telephone rang. The caller was a family friend named Don Wood, a BYU employee who also had cystic fibrosis.

In fact, at 42 years of age, he was one of the oldest surviving victims of the disease in the United States. Ken and Debbie hadn’t been in touch with Don for several years.

Don inquired how they were doing. Ken answered that he wasn’t doing too well.

“It’s Sarah, isn’t it?” Don asked.

“How did you know?” Ken responded.

Don replied that he assumed she had passed away at roughly 6:30 that morning.

Shocked, Ken confirmed that she had died at 6:17 AM. How, he wondered, had Don Wood heard the news?

“I was lying in my bed struggling to breathe,” Don said. “I’ve been on oxygen for some time now, and I wasn’t sure if I would last through the night. At around 6:30 I felt a presence in my room, and, when I looked up, I saw Sarah standing in the air at the foot of my bed. I thought she was coming to take me to the other side, but I was surprised to see her because I didn’t know she had passed away. She was all aglow, and it looked as if light was emanating from her, not just from around her; her entire being was glowing. Her hair was long and curled and she looked beautiful and mature. She didn’t talk out loud, but she communicated with me in a clear voice in my mind. She simply said, ‘I came to tell you, Don, don’t be afraid to die. It’s not scary. I came to tell you that heaven is beautiful.'”

Sarah looked happy and beautiful, Don said, and healthier than he had ever seen her.

Eight months after Sarah died, Don Wood, too, passed away.

“For some people,” Ken McCarty summarizes, “life after death is a hope, something to have faith in. For me, because of our little Sarah, it’s a fact. And, most important of all, it’s beautiful.”

Many scriptures come to mind now.

1 Thessalonians 4:13, for example: “But I would not have you to be ignorant, brethren, concerning them which are asleep, that ye sorrow not, even as others which have no hope.”

And Doctrine and Covenants 42:45-46: “Thou shalt live together in love, insomuch that thou shalt weep for the loss of them that die, and more especially for those that have not hope of a glorious resurrection. And it shall come to pass that those that die in me shall not taste of death, for it shall be sweet unto them.”

It’s understandable that we grieve. Even knowing what he knew and what he was about to do, the Savior himself mourned at the death of his friend Lazarus: “Jesus wept. Then said the Jews, Behold how he loved him!” (See John 11:35-36.)

Critics of the Church, particularly of the secularizing kind who altogether reject theism, and lapsed members sometimes demand of me to know what difference belief in the Gospel makes. Some are focused on social-policy concerns or complaints about unfeeling church leaders or church finances or any number of things that seem to me entirely secondary or even tertiary and have never seemed more so than now. Right now, too, I just don’t care—not even slightly—about those who seem to take delight in cynically mocking and deriding what I and many others hold sacred.

The difference the Gospel makes is utterly clear to me at times such as this. Without it, I would have no hope ever to see Kenneth again.

I’ve been thinking about friends. I include my brother among them: He was a very good friend all of my life, since the time of my earliest memories, and, although I know that time will dull this wound as it has dulled all others, right now the thought of going through the rest of my life without his consistent love and support seems a very bleak and desolate one. Oddly, at my age, I feel truly orphaned. My parents and my only sibling are gone. I never knew my grandfathers and scarcely knew my grandmothers. Nobody remains now from that little house in San Gabriel, California, where my brother and I were raised, and, in fact, even the house itself was demolished a couple of years ago.

In the meantime—in this mean time—my mind has gone back repeatedly to some hymn lyrics by Karen Lynn Davidson, as set to music by A. Laurence Lyon.

Each life that touches ours for good

Reflects thine own great mercy, Lord;

Thou sendest blessings from above

Thru words and deeds of those who love.

What greater gift dost thou bestow,

What greater goodness can we know

Than Christlike friends, whose gentle ways

Strengthen our faith, enrich our days.

When such a friend from us departs,

We hold forever in our hearts

A sweet and hallowed memory,

Bringing us nearer, Lord, to thee.

For worthy friends whose lives proclaim

Devotion to the Savior’s name,

Who bless our days with peace and love,

We praise thy goodness, Lord, above.

All I can do under present circumstances, though, is hope. Not only for a future reunion with my brother, but with all those—parents, aunts and uncles, friends, teachers, Scoutmasters, Church leaders, intellectual mentors—who’ve gone before.

As I say, on Friday afternoon, incapacitated by grief, knowing nothing else to do, I went with my wife to the temple. I confess that I was distracted, hearing only parts of what was said. But there’s a place in the temple that represents our reunion with loved ones beyond the veil, and, on Friday, entering that room, I suddenly struggled to control my emotions for a few seconds as the thought powerfully, distinctly, and rather unexpectedly entered my mind: “Kenneth did this for real—not just symbolically—a few hours ago.”

Decades back, I read an article in a Church magazine about the Hill Cumorah Pageant. I remember nothing from it beyond one sentence: Referring to the sadness of parting from co-workers in the Pageant’s cast and crew after intense days together, a volunteer remarked that the pain was less because “friends in the Gospel never meet for the last time.”

That sentiment has remained with me ever since. I believed it then, and I believe it even now. If actuarial statistics are correct, the wait will probably be far longer than I had wished and hoped, but I will see my brother again, hear his voice, and embrace him. He will, as always, have prepared for my arrival. If he can, he’ll be there to greet me.

“All your losses will be made up to you in the resurrection,” testified the Prophet Joseph Smith, “provided you continue faithful. By the vision of the Almighty I have seen it.”

My brother, a long-time youth leader, high councilor, member of bishoprics, and bishop, was faithful. Now it’s up to me.