Although dating to pre-Islamic times, it has been the center of the Muslim world since the early seventh century.

Sorry, but I’m just going to keep on doing this:

Muslims and Western scholars agree upon a division of the suras or chapters of the Qur’an between those received at Mecca and those later received at the oasis town of Medina. There are differences between the two groups that go considerably beyond the mere time of the reception, however, extending to questions of theme, style, and content. I shall examine the two groups in order.

The revelations of the earliest (Meccan) period of the Prophet’s career have certain recurring themes. One of them is the imminent end of this world. These early revelations are, to use a marvelous, hundred-dollar word, eschatological. The hundredth chapter of the Qur’an is a typical example of the vigorous, poetic quality of its language during this period and, even more, of the apocalyptic themes which characterize many of the earliest revelations:

By the snorting war steeds, which strike fire with their hoofs as they gallop to the raid at dawn and with a trail of dust split the foe in two; man is ungrateful to his Lord! To this he himself shall bear witness.

He loves riches with all his heart. But is he not aware that when the dead are thrown out from their graves and men’s hidden thoughts are laid open their Lord will on that day know all that they have done?

Another representative passage occurs in the eighty-second chapter, entitled Infitaar or “The Splitting”:

When heaven is split open, when the stars are scattered,

when the seas swarm over,

when the tombs are overthrown,

then a soul shall know its works, the former and the latter.[1]

Another theme is the denunciation of the wealthy for their greed and selfishness.[2] Using the mercantile language of Mecca, it describes them as “those that barter guidance for error and forgiveness for punishment.”[3] The wealthy were always so, the Qur’an informs Muhammad,[4] and it quotes God as addressing them directly:

You honour not the orphan, and you urge not the feeding of the needy, and you devour the inheritance greedily, and you love wealth with an ardent love.[5]

Muhammad was directed always to remember his own humble origins and to recall the grace of God in delivering him from them:

Did He not find thee an orphan, and shelter thee? Did He not find thee erring, and guide thee?

Did He not find thee needy, and suffice thee?[6]

His rocky reception at the hands of his Meccan neighbors probably helped to keep him humble, too. There were a number of things about Muhammad and his teaching that the Meccans and others in the audience found extremely difficult to take seriously. “When we are turned to hollow bones,” they asked, “shall we be restored to life?”[7] They knew full well what happened to dead bodies, and their question was purely rhetorical. They were already certain of the answer. “There is no other life but this; nor shall we ever be raised to life again.”[8] “There is this life and no other. We live and die; nothing but Time destroys us.”[9] “When we and our fathers are turned to dust, shall we be raised to life? We were promised this once before, and so were our fathers. It is but a fable of the ancients.”[10]

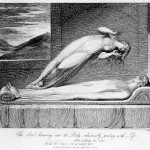

The Qur’an, however, insists upon the literal reality of physical resurrection, which it frequently compares to the resuscitation of fields after a rain.[11] It also points out that God, who was able to create the universe in the first place, and whose creative power gives rise to our physical bodies, will certainly be able to recreate our bodies after their dissolution in death. That, it says, is a relatively small thing.[12] And, finally, the Qur’an points to the motive of the unbelievers in denying the resurrection of the dead. Numerous skeptics today say that belief in life after death is a childish notion, tailor-made for those who fear death. But for many, especially for many in premodern times who believed firmly that any God who existed must be a God of judgment, it was often disbelief in life after death that was comforting. “Eat, drink, and be merry,” the Book of Mormon quotes such people as saying, “for tomorrow we die; and it shall be well with us.”[13] The Qur’an, however, will not allow unbelievers to rest secure in their disbelief. It quotes their familiar rhetorical question and then directs Muhammad how to answer: “`What! When we are dead and turned to dust and bones, shall we be raised to life, we and our forefathers?’ Say: `Yes. And you shall be held in shame. “‘28

[1] 82:1-5; Arberry.

[2] For example, at 70:11-18; 104:1-3.

[3] 2:175. The notion that Islam is somehow a religion of the desert is, on the whole, false. Much nonsense has been written on this theme, trying, for instance to derive the alleged “harshness” of the religion from the severity of the Arabian desert, or to deduce its strict monotheism from the simplicity of Arabian sand and sky. In reality, Islam was born in a commercial center and constantly uses commercial language, in much the same way that Jesus tended to use the language of sheep herding and agriculture, in order to make its points understandable to its audience. The true desert Arabs, the bedouins, are criticized by the Qur’an; their Islam is seen as suspect. (See, for example, 49:14.)

[4] 34:34-35.

[5] 89:17-20; Arberry.

[6] 93:6-8; Arberry.

[7] 79:10-11; compare 13:5; 17:49-52; 19:66; 23:35-37; 34:7; 44:35-36; 50:3; 56:47-48; 64:7.

[8] 6:29.

[9] 45:24.

[10] 27:67-68; compare 23:82-83.

[11] 75:3-4; 7:57; 22:5-8; 30:50; 35:9; 41:39; 43:10-13; 50:6-11.

[12] 36:77-79; 46:33. See also the discussion of these arguments in Daniel C. Peterson, “Does the Qur’an Teach Creation Ex Nihilo?” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W Nibley, edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City and Provo: Deseret Book and the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1990), 1:584-610.

[13] 2 Nephi 28:7. The next verse seems to refer to those who do believe in life after death, but do not believe that God will truly judge them for their sins.