(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo by Nick Allen)

Dr. Ian H. Hutchinson is Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with a primary research interest in plasma physics. In this passage from his book Monopolizing Knowledge, he takes aim at “reductionism”:

It is the assertion, or more usually unspoken presumption, that when a satisfactory scientific explanation at a reduced level exists, such an explanation trumps, invalidates, or explains away understanding at higher levels: that the higher level descriptions lose their force or relevance. This is certainly what, for example, Donald MacKay in his The clockwork image (1974) is complaining about, and why he coined the disparaging but descriptive phrase “nothing-buttery” to refer to ontological reductionism. “Nothing-buttery is characterized by the notion that by reducing any phenomenon to its components you not only explain it, but explain it away.” It is definitely helpful to analyze animal bodies in terms of their cells, but it is unhelpful, and fundamentally untrue, to conclude that if one completes such an analysis, then animals are demonstrated to be nothing but assemblies of cells. The presumption that reduced level explanations explain away higher level descriptions generally operates inconsistently. It must do so, because science is full of descriptions and explanations that are actually not reductionist in the senses identified by [Richard] Dawkins and [Michael] Ruse. Nothing-buttery usually operates in such a way as to discriminate against the descriptions that don’t conform to the ideals of science. We shall examine later some examples of this process at work, but here we simply draw attention to the fact that it is a trait of scientism.

(Ian Hutchinson, Monopolizing Knowledge [Belmont, MA: Fias Publishing, 2011], 1-3)

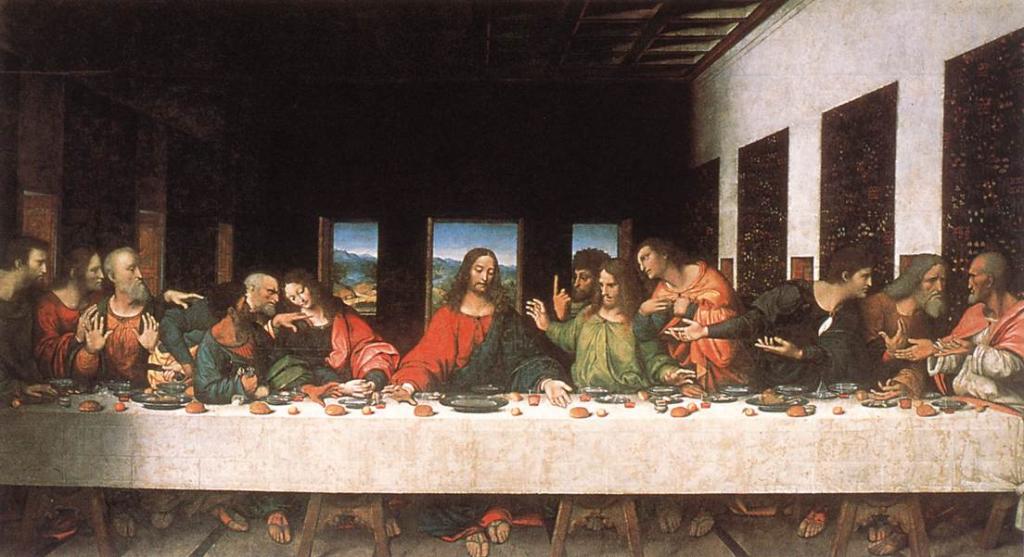

Illustrative specimens that come to mind might include, among almost infinitely many others, any painting by Leonardo da Vinci. Nobody, I trust, would seriously propose that one had really thoroughly understood his “fresco” of The Last Supper by measuring it precisely, calculating the chemical composition of the various pigments, determining their depth on the wall, and so forth, while excluding Leonardo’s purpose in creating it and in making it just as it is, the historical background of the painting (including the New Testament story that it represents), the intentions of those who commissioned it, its function in the room of Milan’s Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie where it appears, the function of that room itself, the economy of late-fifteenth-century Florence, and a host of other potentially fruitful approaches.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

If one could somehow construct an exhaustive and accurate account of the synaptic firings in Shakespeare’s brain (or the Earl of Oxford’s, or whatever author you prefer) during the time that he was writing King Lear, would doing so actually help very much, if at all, in fully understanding or appreciating that very great play?