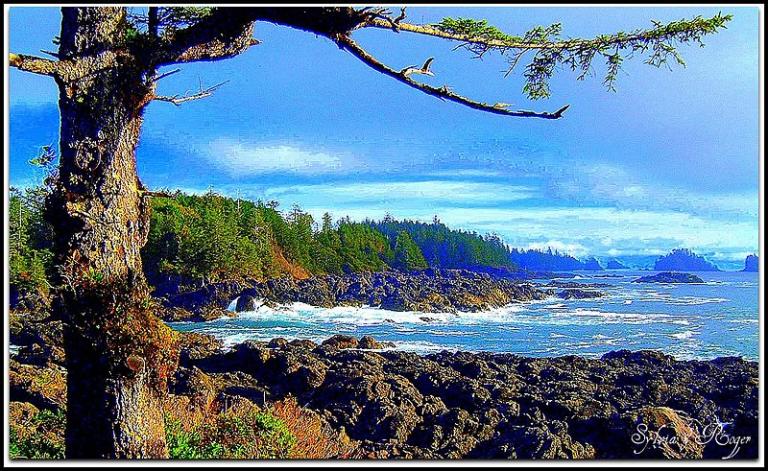

(Wikimedia Commons photograph by Roger Sylvia)

“Doctors and their medicines I regard as a deadly bane to any community. . . . I am not very partial to doctors. . . . I can see no use for them unless it is to raise grain or go to mechanical work.” (Brigham Young, Journal of Discourses 4:109 [3 August 1869])

A few days ago, I posted something in which I briefly defended Brigham Young’s negative comments about doctors and medicine, which, I said, made perfect sense in light of the track record of the medicine of his time. (Critics have occasionally abused such remarks to paint him as anti-scientific.) Modern medicine, with its successes, was still in its early years during Brigham’s lifetime (and particularly so in his youth and early adulthood), and many physicians of the day were little better than — and in some cases, much worse than — quacks. Here’s what I wrote:

“A bit more on science during the Middle Ages, with a note in defense of Brigham Young”

I’ll follow up on that with a few more notes from James Hannam, The Genesis of Science: How the Christian Middle Ages Launched the Scientific Revolution (Washington DC: Henry Regnery, 2011). Here, Dr. Hannam is writing about Girolamo Cardano (b. 1501), who is better known in the English-speaking world as Jerome Cardan, and who was both the foremost astrologer and the foremost physician of his day:

Cardan’s success as a physician was almost entirely due to his philosophy of non-intervention. His peers tortured their patients with a gruesome regime of bleedings, purgatives, and potions guaranteed to weaken the constitution of even the hardiest soul. As we have already seen, doctors of the time based their theories on a mixture of Galen and the Arabic medical writers, with a dose of natural magic and plenty of guesswork. Merely by sporting a professional qualification, doctors could demand hefty fees for accelerating the demise of their clients. This is surely the reason that so many people put their trust in the village wise women and the intercession of the saints. Both were much less likely to kill them before they had a chance to get better on their own.

Whether by intuition or genius, Cardan gave his patients a chance to heal themselves. Rather than the constant round of prescriptions and bloodletting, he suggested a healthy diet and plenty of rest. In this way, he gained a reputation far beyond the borders of Italy as a doctor without parallel. (237)

And another relevant passage:

Given the demise of the magical worldview in polite society, the doctrine of sympathy and other alternatives also fell from favor. Protestants even tended to reject religious miracles. Somehow, scientific medicine had seen off its main rivals while actually being less effective than either of them. Thus, the history of medicine until the mid-nineteenth century, with the significant exception of smallpox vaccination, is a history of failure. Most doctors [for example] were comfortably oblivious to the damage they were doing by bleeding their patients . . . (265)

For a relatively recent American illustration of that last point, see “Bloodletting and blisters: Solving the medical mystery of George Washington’s death.”

Posted from Ucluelet, British Columbia