Original Title: Comprehensive Response to Protestant Robin Phillips’ Essay, “Why I am Not a Roman Catholic”

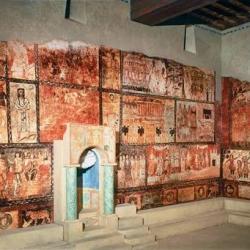

Crepuscular Rays at Noon in Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photograph by Alex Proimos (7-11-11) [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license]

(1-31-12)

Robin Phillips is co-director of the Reformed Liturgical Institute. he studied philosophy at London University and received a B.A. in Western Civilization from the UK’s Open University. He was a history teacher at the Classical Christian Academy in Idaho, where he developed a six year curriculum spanning all of Western Civilization. Currently he is working on a PhD in historical theology (King’s College, London). He is the director of the Alfred the Great Society, a columnist for the Chuck Colson Center and the Spokane Libertarian Examiner, the author of the monthly ‘Letter from America’ and ‘The Persecuted Church’ columns for the Christian Voice magazine. In addition to these positions he also acts as a contributing author for Touchstone, Fermentations, The Jonathan Edwards Society, World Net Daily, the Kuyper Foundation’s biannual Journal Christianity & Society, Northwind, Salvo Magazine, and their blog Signs of the Times. His book, The Decent Drapery of Life is currently scheduled for publication with Wipf and Stock; his volume, Saints and Scoundrels will be published by Canon Press in 2012. He has also compiled a collection of his essays: The Twilight of Liberalism (Lulu, 2011).

Theologically, Phillips describes himself as

“kind of a Calvinist,” and “passionately Trinitarian, avidly covenantal, fervently post-millennial, unashamedly ecumenical.”

The following is a point-by-point response to his essay,

Why I am Not a Roman Catholic (12 December 2011): posted at his website,

Robin’s Readings and Reflections. It is cited in its entirety, in

blue, with the exception of the portions at the end of his essay that specifically address “traditionalist” Catholics (they can defend themselves!). All words in black are my own.

* * * * *

Earlier in the year my friend Brad Littlejohn wrote an article for his blog titled ‘Why I Won’t Convert’, outlining his continued commitment to Protestantism. Now it’s my turn. Having used my previous post to reaffirm my commitment to Calvinism (kind of), I wanted to use the present post as an opportunity to explain why I am not a Roman Catholic.

I always appreciate clarifications / affirmations of this sort, from Protestant brethren who are not weighed down by the silly and logically circular mindset of anti-Catholicism. It also gives me a great opportunity to make a Catholic response; to “bounce off” the thoughts and to be intellectually stimulated to make a further defense of Catholicism, as the case may be. I enjoy few things more.

First the qualifications. Keep in mind that I am still in the process of learning about Roman Catholicism and I do not claim any expert knowledge. I cannot even guarantee that what I will say is not tinctured with protestant caricatures or inadvertent uncharities. I am hoping my Roman Catholic brothers and sisters will enlighten me on any factual mistakes in what follows.

Glad to be of any service. I appreciate the “humble” approach.

The purpose of this post is not to claim any special authority on Roman Catholicism, but simply to explain from a personal point of view why I have not chosen to convert. What follows is not written out of any sense of antagonism towards Roman Catholics. Rather, it was written after feeling pressure from a traditionalist Roman Catholic brother that I should convert to Rome. (No problem there: if someone believes that RC is the true church, they should want to convert me out of love. But equally, it only seems fair I should respond by explaining the reasons I have chosen not to convert.)

Perfectly understandable and acceptable . . .

Finally, although I will be critical of Roman Catholicism, this should not be taken as overshadowing my strong commitment to ecumenism that I have articulated elsewhere (see my article, ‘Sola Fide: The Great Ecumenical Doctrine’) nor my belief that Roman Catholics are Christians.

Fully understood. It sounds like Robin is very much of the mind that I am, myself: committed to both apologetics (in a charitable way) and ecumenism. That is why I look forward to this so much. It’s refreshing. This is how it should be among Christians.

One of the primary reasons I have not converted to Rome is because Rome does not seem to be Catholic enough. Consider just three areas where Protestants normally find fault with Rome: (A) Rome’s sacramentalism; (B) Rome’s claims to universality; (C) Rome’s concept of authoritative traditions or the magisterium.

Now these three areas are indeed problems, but not because Rome puts too much emphasis on these things, as Protestants often erroneously claim, but too less. The real reason Rome’s sacramentalism is a problem is not because she is too sacramental, but because she is not sacramental enough. The real reason that Rome’s claim to universality is a problem is not because she claims universality but because she isn’t universal enough. The real reason that Rome’s concept of an authoritative tradition is a problem is because her traditions are not authoritative enough. Let’s take each of these in turn.

A curious thesis . . . okay, let’s see where this goes.

Rome Trivializes the Sacraments

In practice, Rome seems to minimize the importance of the sacraments. Think of the way the blessed Eucharist was functionally devalued in medieval Europe within a system that was prepared to deny wine to the laity and restrict even the bread to annual services.

But communion in one kind is not

automatically a “trivialization.” The fact remains that within the assumption of bodily Real Presence, Jesus is fully present under either form (since He can’t be divided). This is a biblical teaching:

1 Corinthians 11:27 (RSV, as throughout) Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord.

Note the all-important “or.” This shows that Jesus is fully present in

either. If we profane the consecrated host, we are guilty of the body and blood of Christ. The logic (even the grammatical structure or syntax) is unassailable. Jesus Himself also alludes to one form only being salvific:

John 6:33-35 For the bread of God is that which comes down from heaven, and gives life to the world.” [34] They said to him, “Lord, give us this bread always.” [35] Jesus said to them, “I am the bread of life; he who comes to me shall not hunger, and he who believes in me shall never thirst.

John 6:50-51 This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. [51] I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.

John 6:57-58 As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats me will live because of me. [58] This is the bread which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live for ever.

These passages don’t exclude both forms, but they do show that one only is quite sufficient for the purpose of receiving our Lord Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity: a thing directly tied to salvation (John 6). The widespread withdrawal of the cup had nothing to do with a goal of deliberate deprivation, and everything to do with hygienic and reverential considerations. It was much easier for abuse to take place with liquid. It was also more difficult and risk-laden to take the Eucharist to the sick in their homes (as was widely done in the early Church) in liquid form.

When many Protestants later ceased believing in the Real Substantial Presence altogether, such considerations were irrelevant: a little wine (or the unbiblical grape juice, due to the social pressure of the temperance movement) splashes out? So what: it’s only symbolic, anyway. No biggie. But when one believes that it is literally our Lord Jesus, then the utmost care is taken.

Moreover, how sacraments or liturgy are conducted in details is a relevant consideration as well. I could just as well argue that the Calvinist tradition trivialized baptism by not routinely using immersion, which seems indicated or some kind of norm, at least in some Bible passages. It was deemed a proper development and not fatal to the essence of baptism, by most Protestants, to allow pouring or even sprinkling. The Baptist would argue, on the other hand, that immersion as well as adult baptism are both central or essential to the rite. Most Christians (including the majority of Protestant) disagree.

Lastly, those of us who believe in baptismal regeneration (the vast majority of all Christians throughout history) also hold that to deny that result is to violate the very essence of the sacrament: to “gut it” of its power and central purpose. But these are the same kinds of arguments made with regard to Holy Communion: because Rome didn’t allow the cup for many years, somehow it is “trivializing” the sacrament. It simply doesn’t follow; and the more one understands the reasoning, the less force this objection has. I hope Robin can be thus persuaded to drop it as an objection.

The only case that has any “teeth” at all here is the complaint about infrequent communion. But the Church in due course changed that. I’m not sure what the earlier rationale was.

Or again, consider the way Rome trivializes the Eucharist by allowing those who support abortion and even homosexuality to have access to Christ’s body and blood merely because they are Roman Catholics.

I agree that there should be more vigilance on the part of priests in this regard; however, all this proves is that there is some abuse of the norm. It proves nothing one way or the other as to the theological truth-claims of Catholicism. The claim of “there are abuses, therefore the system itself is unworthy to be adhered to and is untrue” is filled with logical fallacies that I think are apparent, upon a little reflection. I trust my readers enough to not feel that I have to spend any further time explaining why.

The bottom-line questions is: who offers the true sacraments, as understood throughout the history of the Church (which ties into apostolic succession), and who does not? That is what has to be determined, and when the answer is found, the seeker is duty-bound to follow the truth wherever it leads. Abuses are present in any human organization, insofar as human elements are necessarily involved. It’s a legitimate concern but not a “system-defeater.”

Such people would be quickly excommunicated in conservative Protestant churches and in the early church (see Paul’s correspondence with the Corinthians) and yet are allowed full table privileges in Rome. The patience and slowness of the Roman Catholic church on these matters is an innovation compared to the early church.

It’s true that more “conservative” Protestant denominations and congregations will usually take a harder line on issues of this sort (thank God for that); however, it still remains true that Protestantism as a whole is precisely that portion of Christianity which has most massively compromised with modernism and the sexual revolution. Important parts of it have not (again, thank God) but the historical tendency is clearly a strong trend toward liberalization and compromise. Hence, it is a fact that there are now entire denominations, including virtually all of mainstream Protestantism, that espouse legal abortion and homosexual practice; even clergy.

Catholicism, on the other hand, is as firmly against abortion as always, and against homosexual acts. That is our dogmatic teaching. How it is applied or “enforced” is a separate (and to me, far lesser) issue of concern. But it seems to me that if the larger issue is “why or why not to be a Catholic?”, it can’t be based only on a consideration of abuses. The far more important consideration is: what does a Christian body teach as to the rightness and wrongness of various acts, such as abortion, etc.?

I am a Catholic myself in large part because I was sick and tired of Protestant compromise dogmatically with the sexual revolution and modern immorality in general. I looked to see which group had maintained traditional moral teachings in their entirety, and there was only one clear choice: Catholicism. We forbid divorce, abortion, contraception (a thing all Christians prohibited until 1930), and we alone hold to apostolic (and biblical) morality in its entirety. I didn’t expect that all individual Catholics would adhere perfectly to all this, since we are a fallen human race. I didn’t become a Catholic because Catholics were outwardly more saintly than everyone else (heavens no!). I did because it was the fullness of Christian truth, I came to conclude (and particularly impressive and unique in its moral teaching).

Rome is to be applauded for her high view of the Eucharist, but we do right to protest against her for not holding a higher view.

But I respectfully submit that all these objections (save one, which is no longer even an issue, and is in the nature of a past shortcoming)

fail, per my reasoning above, and certainly any form of Protestantism is more vulnerable to the same criticisms.

Rome Isn’t Catholic Enough

Rome is right to emphasize the importance of the church’s visible unity and catholicity, and Protestants have much to learn from catholic teaching in this area. Yet when Rome excommunicated many eastern patriarchs in the 11th century and continues to be incredibly slow about pursuing institutional unity with the Eastern Orthodox church since they do not accept the supremacy of the Roman pontiff (though there is some hope things may change during the present millennium), one has to wonder how deep her commitment to visible unity really runs.

The mutual anathemas have been lifted. No one has been more desirous of a reunion than the Catholic Church. Several times in recent years it seemed within reach, but invariably it was factions in Eastern Orthodoxy that sunk it (just as in the Council of Florence in the 15th century). It is odd, then, that we are criticized for what is far more a widespread practice and difficulty within Orthodoxy.

(The Eastern Orthodox churches came back in union with Rome in 1096, which lasted until 1204 when the horrendous behaviour of the crusaders destroyed all hope of unity.

That works both ways. This presents the usual one-sided view that it was all our fault. There were horrendous sins committed by Catholics, but also (what we never hear about) by the Orthodox. In Wikipedia, (“Eastern Orthodox Church”) it is noted:

In 2004, Pope John Paul II extended a formal apology for the sacking of Constantinople in 1204, which was importantly also strongly condemned by the Pope at the time (Innocent III, . . .); the apology was formally accepted by Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople.

Pope Innocent II was outraged at the sacking of Constantinople. His scathing

letter of condemnation reads in part:

How, indeed, is the Greek church to be brought back into ecclesiastical union and to a devotion for the Apostolic See when she has been beset with so many afflictions and persecutions that she sees in the Latins only an example of perdition and the works of darkness, so that she now, and with reason, detests the Latins more than dogs? As for those who were supposed to be seeking the ends of Jesus Christ, not their own ends, whose swords, which they were supposed to use against the pagans, are now dripping with Christian blood they have spared neither age nor sex. They have committed incest, adultery, and fornication before the eyes of men. They have exposed both matrons and virgins, even those dedicated to God, to the sordid lusts of boys. Not satisfied with breaking open the imperial treasury and plundering the goods of princes and lesser men, they also laid their hands on the treasures of the churches and, what is more serious, on their very possessions. They have even ripped silver plates from the altars and have hacked them to pieces among themselves. They violated the holy places and have carried off crosses and relics.

During the 15th century in Florence the Roman Catholic church held a council which decreed the necessity of being in submission to the Roman pontiff, and the patriarchs of the East accepted this while Rome in turn recognized the legitimacy of the Eastern Patriarchs. However, when the Patriarchs when back to the East their people rejected what had been decided and replaced the Patriarchs with bishops who did not accept the primacy of Rome.

Just as I noted above: reunion was quite achievable then, but the masses, in their strong prejudice against the “Latins” wrecked any hope of it. This prejudice was so deep that even western offers of military aid against the Turks were rejected, and Constantinople was overrun in 1453: just eight years after the ecumenical council ended.

Even so, to this day Rome accepts the legitimacy of the Eastern Orthodox churches in a qualified sense and allows them to participate in the blessed Eucharist, though the same does not apply the other way round: according to a series of decrees, EO’s can officially have communion in RC churches but RC’s cannot officially have communion in EO churches.)

More evidence that we are relatively more ecumenical . . . I find this whole line of reasoning odd and curiously insubstantial. It’s clear that we have been (on the whole, and especially recently) more “Catholic” than the Orthodox have been. Yet the present charge is directed against the Catholic Church. In any event, I don’t see how these objections succeed in their aim. I see no reason here to not be a Catholic.

What then of Rome’s attitude towards Protestants? Even when Vatican II’s Decree on Ecumenism acknowledged that some Protestants are “members of Christ’s body” (3.20), part of “Christian communions,” (1) and “justified by faith,” (3.20), Rome still didn’t have the guts to officially retract her earlier sectarian statements to the contrary.

The Catholic Church made all kinds of positive ecumenical statements about Protestants.

Does Vatican II’s Decree on Ecumenism mean that Pius XII Mystici Corporis Christi is no longer accurate, specifically when it gave submission to the Roman hierarchy as one of the four conditions to church membership?

Catholics distinguish between implicit and explicit membership in the Church. Ours is an infinitely better and more charitable view compared to the confessions and creeds of most Protestant denominations, which routinely class us with the antichrist or Whore of Babylon. The Lutheran Confessions (even after the allegedly profoundly ecumenical Augsburg Confession), describe the Catholic Mass as akin to the worship of Baal. Thus these charges ring rather hollow.

The Catholic Church is clearly committed to ecumenism. There has been a rapid and welcome development of this line of thought in the last 60-70 years. The historic “difficulties” present some problems to work through but the Catholic position through the centuries can be defended. I have done so, myself, in demonstrating, e.g., that ecumenical motifs were present in St. Thomas Aquinas and others, and are not completely new. But the emphasis of the Church has definitely changed.

Similarly, since the Anathemas of the Council of Trent and Pope Pius IX’s ‘

Syllabus of Errors’

still officially stand (both of which gathered together in one spot teaching that was already part of the magisterium), both Protestants as well as Roman Catholics have been struggling to understand just how serious Rome’s claims to catholicity are in the post-Vatican II world.

This is also massively misunderstood. Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin showed in a superb 1996 paper,

“Justification by Faith Alone,” how the Tridentine anathemas do

not apply to most Protestants:

The three theological virtues of Catholic theology are thus summed up in the (good) Protestant’s idea of the virtue of faith. And the Protestant slogan “salvation by faith alone” becomes the Catholic slogan “salvation by faith, hope, and charity (alone).”

This was recognized a few years ago in The Church’s Confession of Faith: A Catholic Catechism for Adults, put out by the German Conference of Bishops, which stated:

Catholic doctrine . . . says that only a faith alive in graciously bestowed love can justify. Having “mere” faith without love, merely considering something true, does not justify us. But if one understands faith in the full and comprehensive biblical sense, then faith includes conversion, hope, and love . . . According to Catholic doctrine, faith encompasses both trusting in God on the basis of his mercifulness proved in Jesus Christ and confessing the salvific work of God through Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit. Yet this faith is never alone. It includes other acts.

The same thing was recognized in a document written a few years ago under the auspices of the (Catholic) German Conference of Bishops and the bishops of the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany (the Lutheran church). The purpose of the document, titled The Condemnations of the Reformation Era: Do They Still Divide?, was to determine which of the sixteenth-century Catholic and Protestant condemnations are still applicable to the other party. Thus the joint committee which drafted the document went over the condemnations from Trent and assessed which of them no longer applied to Lutherans and the condemnations of the Augsburg Confession and the Smalcald Articles, etc., and assesses which of them are not applicable to Catholics.

When it came to the issue of justification by faith alone, the document concluded:

“[T]oday the difference about our interpretation of faith is no longer a reason for mutual condemnation . . . even though in the Reformation period it was seen as a profound antithesis of ultimate and decisive force. By this we mean the confrontation between the formulas ‘by faith alone,’ on the one hand, and ‘faith, hope, and love,’ on the other.

“We may follow Cardinal Willebrand and say: ‘In Luther’s sense the word ‘faith’ by no means intends to exclude either works or love or even hope. We may quite justly say that Luther’s concept of faith, if we take it in its fullest sense, surely means nothing other than what we in the Catholic Church term love’ (1970, at the General Assembly of the World Lutheran Federation in Evian).

If we take all this to heart, we may say the following: If we translate from one language to another, then Protestant talk about justification through faith corresponds to Catholic talk about justification through grace; and on the other hand, Protestant doctrine understands substantially under the one word ‘faith’ what Catholic doctrine (following 1 Cor. 13:13) sums up in the triad of ‘faith, hope, and love.’ But in this case the mutual rejections in this question can be viewed as no longer applicable today

“According to [Lutheran] Protestant interpretation, the faith that clings unconditionally to God’s promise in Word and Sacrament is sufficient for righteousness before God, so that the renewal of the human being, without which there can be no faith, does not in itself make any contribution to justification. Catholic doctrine knows itself to be at one with the Protestant concern in emphasizing that the renewal of the human being does not ‘contribute’ to justification, and is certainly not a contribution to which he could make any appeal before God. Nevertheless it feels compelled to stress the renewal of the human being through justifying grace, for the sake of acknowledging God’s newly creating power; although this renewal in faith, hope, and love is certainly nothing but a response to God’s unfathomable grace. Only if we observe this distinction can we say

“In addition to concluding that canons 9 and 12 of the Decree on Justification did not apply to modern Protestants, the document also concluded that canons 1-13, 16, 24, and 32 do not apply to modern Protestants (or at least modern Lutherans).”

During the drafting of this document, the Protestant participants asked what kind of authority it would have in the Catholic Church, and the response given by Cardinal Ratzinger (who was the Catholic corresponding head of the joint commission) was that it would have considerable authority. The German Conference of Bishops is well-known in the Catholic Church for being very cautious and orthodox and thus the document would carry a great deal of weight even outside of Germany, where the Protestant Reformation started.

Furthermore, the Catholic head of the joint commission was Ratzinger himself, who is also the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Rome, which is the body charged by the pope with protecting the purity of Catholic doctrine. Next to the pope himself, the head of the CDF is the man most responsible for protecting orthodox Catholic teaching, and the head of the CDF happened to be the Catholic official with ultimate oversight over the drafting of the document.

Before the joint commission met, Cardinal Ratzinger and Lutheran Bishop Eduard Lohse (head of the Lutheran church in Germany) issued a letter expressing the purpose of the document, stating:

“[O]ur common witness is counteracted by judgments passed by one church on the other during the sixteenth century, judgments which found their way into the Confession of the Lutheran and Reformed churches and into the doctrinal decisions of the Council of Trent. According to the general conviction, these so-called condemnations no longer apply to our partner today. But this must not remain a merely private persuasion. It must be established in binding form.”

I say this as a preface to noting that the commission concluded that canon 9 of Trent’s Decree on Justification is not applicable to modern Protestants (or at least those who say saving faith is Galatians 5 faith). This is important because canon 9 is the one dealing with the “faith alone” formula (and the one R.C. Sproul is continually hopping up and down about). It states:

“If anyone says that the sinner is justified by faith alone, so as to understand that nothing else is required to cooperate in the attainment of the grace of justification . . . let him be anathema.”

The reason this is not applicable to modern Protestants is that Protestants (at least the good ones) do not hold the view being condemned in this canon.

Like all Catholic documents of the period, it uses the term “faith” in the sense of intellectual belief in whatever God says. Thus the position being condemned is the idea that we are justified by intellectual assent alone (as per James 2). We might rephrase the canon:

“If anyone says that the sinner is justified by intellectual assent alone, so as to understand that nothing besides intellectual assent is required to cooperate in the attainment of the grace of justification . . . let him be anathema.”

And every non-antinomian Protestant would agree with this, since in addition to intellectual assent one must also repent, trust, etc.

So Trent does not condemn the (better) Protestant understanding of faith alone. In fact, the canon allows the formula to be used so long as it is not used so as to understand that nothing besides intellectual assent is required. The canon only condemns “sola fide” if it is used “so as to understand that nothing else [besides intellectual assent] is required” to attain justification. Thus Trent is only condemning one interpretation of the sola fide formula and not the formula itself.

I should mention at this point that I think Trent was absolutely right in what it did and that it phrased the canon in the perfect manner to be understood by the Catholic faithful of the time. The term “faith” had long been established as referring to intellectual assent, as per Romans 14:22-23, James 2:14-26, 1 Corinthians 13:13, etc., and thus everyday usage of the formula “faith alone” had to be squashed in the Catholic community because it would be understood to mean “intellectual assent alone”.

Note that these ecumenical sentiments were wholeheartedly espoused by none other than the present pope: Benedict XVI (formerly Joseph Ratzinger). We can continue to be stuck in the mutual anathemas of the 16th century or we can move ahead, with this sort of charitable understanding of each other. One may not want to become a Catholic, but at least (hopefully) our position can be correctly understood, as it is clarified and explained in greater detail.

So while I applaud Rome for holding a high view of catholicity, I think we do right to protest against her for not holding a higher view.

I don’t see anyone else holding a higher view than we do. If the procedure is to present a (well-meaning but still . . .) caricature of what our view is, knock that down, and pass on presenting any superior alternate view, then obviously, a person will conclude against Catholicism. But nothing is accomplished in terms of a true comparison of relative merits. The present paper allows readers a chance to:

1) See various Protestant criticisms of Catholicism;

and also

2) See how a Catholic apologist responds.

Read both sides and make up your minds which side is more plausible and worthy of belief!

Rome’s lack of catholicity leads to a misunderstanding of the sacraments. Even though the Second Vatican Council’s ‘Decree on Ecumenism’ acknowledges Protestants to be “members of Christ’s body” (3.20), part of “Christian communions,” (1) “justified by faith,” (3.20) and that Protestants as Protestants have “access to the community of salvation,” (1.22) Protestants are still bared from participating in the blessed Eucharist with them, thus introducing an unchurchly division between the rite of baptism and the sacrament of holy communion.

This is because, in the Bible and early Church one must believe the entirety of Catholic beliefs before partaking in the Eucharist. This is the reason why there were very lengthy periods of time for catechumens. Almost all Protestants do not believe as we do regarding the Eucharist: and our view is demonstrably the prevailing one throughout Church history. One of the Protestant denominations that is closer to our view: the Missouri Synod Lutherans, also has closed communion, so it is not a characteristic unique to us. The Orthodox do not allow us to commune with them.

But the more one departs from traditional eucharistic belief, the more lax one will be as to whom are allowed to partake of communion. This is how liberal ersatz so-called “ecumenism” works: the less one believes, the more they can band together and unite organizationally.

This is sometimes defended on the grounds that Protestants do not believe that the Eucharist is really the body and blood of Christ; however, most of the Protestants I know do accept that the Eucharist is the body and blood of Christ in some sense, and so it is difficult for me to take this argument very seriously.

For the Catholic “some sense” is not sufficient. it is this argument that is doctrinally lax and unserious. It thumbs its nose at Christian and Catholic tradition, as altogether foolish and insubstantial (no pun intended). We believe that the consecrated Eucharist is truly our Lord Jesus: Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity. Thus, we can hardly allow someone to partake who doesn’t even agree. But in our view (which is apostolic and patristic) there is a necessity to accept all that the Church teaches: not just concerning the Eucharist: to be admitted both to the Church and the Church’s table.

Again, for Protestants to whom agreement in doctrine is a relative trifle, none of that matters. But if doctrine did matter deeply to them, they should be the first to understand this relatively elementary principle: “believe in a group’s teachings before being admitted to its most sacred and important rites.” To me (including when I was Protestant) it’s always been a no-brainer, but many people have the hardest time with this. I’ve never understood why.

Make no mistake, Rome does acknowledge the Trinitarian baptisms of Protestants to be valid, which is why Protestants who convert to these traditions do not have to be re-baptized. Yet despite the fact that Rome recognizes Protestant baptisms as being legitimate in a way that the baptisms of heretical sects (i.e., Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses) are not, such baptisms are still seen as being insufficient to establish Eucharistic fellowship.

That’s correct: on the grounds above. The true faith is one, and cannot be divided up. That’s what we believe:

Ephesians 4:4-5 There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, [5] one Lord, one faith, one baptism,

In light of Galatians 2 (which I discuss here), I wonder what would Paul say about a group of Christians who excluded from the Eucharist all other believers simply because they do not believe in doctrines like the immaculate conception or the assumption of Mary or papal infallibility – doctrines which I am quite certain Paul himself never heard of.

He would say what he always says: that there is one body of apostolic tradition, whose content is known, and it is to be unconditionally accepted. Those who do not are the ones causing division and scandal. He also stated the following: showing definitively that he believed in the Substantial Real Presence (therefore, those who did not would obviously be excluded by him from the rite, since they would be not sufficiently catechized as Catholics):

1 Corinthians 10:16-17 The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? [17] Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread. (cf. 11:27, seen above)

Paul also believed that the Eucharist involved a sacrifice (and all Protestants reject that, save for a tiny number of anglo-Catholics). I provide several biblical arguments for why I believe that, in my book, Biblical Catholic Eucharistic Theology.

Rome Trivializes Tradition

Rome is to be applauded for her high view of tradition, but we do right to protest against her for not holding a higher view.

Now I’m starting to detect a pattern of argument . . . thus far, it is a failed one.

Think of the way Vatican II rendered some of the Church’s past tradition meaningless by reinterpreting the meaning of past documents without recourse to authorial intent, rather like liberal judges routinely do with the American constitution.

The usual Protestant misunderstanding of development of doctrine vs. evolution of dogma (condemned by the Catholic Church) . . . Vatican II overturned no dogma of the Church; it merely developed them. Some things, such as the issue of religious freedom in particular (more on that below), were not dogmas in the first place, but issues of social policy and the relation of Church and state. Thus, there was considerably more freedom to expand the understanding of those: a lot more “leeway.”

When a Protestant succumbs to the impulse of liberalism, all he has to do is to say that he no longer assents with his church’s historic confessions, whether it be the 39 Articles or the Westminster Confession of Faith. But when a Roman Catholic becomes liberal, he cannot reject the infallible magisterium and so he simply reinterprets it.

That’s correct. And this is precisely what the Catholic dissidents who rejected the substance of Vatican II did. They simply pretended that it was something that it was not. But of course there are plenty of Protestants who play games with words in the same way. Presbyterian populist apologist Francis Schaeffer wrote an entire book about it:

The Great Evangelical Disaster: comparing the 80s to the 20s. He cited J. Gresham Machen’s

Christianity and Liberalism, that described the same process of equivocation and intellectual dishonesty that is the liberals’ stock-in-trade. So it is just as prevalent in Protestantism.

Hence, a statement like Cyprian’s Extra ecclesiam nulla salus (“outside the church there is no salvation”) which was once used to exclude Protestants, is now interpreted in a way that includes Hindus (at least, according to some of the more liberal interpretations of Mystici Corporis Christi of 1943).

Very long discussion. I have many articles about it on my “Ecumenism” page.

Such fluid hermeneutics are often defended by Newman’s ‘development of doctrine’ theory, though it leads one into cases of serious historical anachronisms.

Not in the slightest. I know a little about Cardinal Newman. I have a large web page about him, development of doctrine is my favorite theological topic (I even wrote a book about it); he was the biggest influence in my conversion, and I recently completed a book of his quotations, that is to be published by Sophia Institute Press. Development (in the conjunction with the history of Catholicism) can be thoroughly defended, and I have done so many times. It is very poorly understood by many many people, including Catholics. But we would expect this of any brilliant, nuanced thought such as Newman’s.

Consider, for example, the Declaration on Religious Freedom known as ‘Dignitatis Humanae’ (and which can be read on the Vatican’s website here)

. This document, which made its way into Vatican II, says that all nations have a right to public and private worship, thus contradicting (or ‘reinterpreting’ in good Roman Catholic form) Pope Leo XIII’s formal statements to the contrary.

I already dealt with this bogus charge above. See also the papers noted above on “no salvation outside the Church” for coherent replies.

Given this fluidity, I often find it very confusing trying to figure out just what the Roman Catholic church officially believes.

That is easy enough to determine: simply read the

Catechism of the Catholic Church (

available online). It’s far easier to find out what we believe than it is with almost any Protestant denomination.

I have tried to resolve this dilemma by speaking to Roman Catholic friends of mine, but it is not uncommon that I receive differing, even contradictory, answers. One person told me that if I am confused trying to navigate through all the contradictions and figure out what the Roman Catholic church officially teaches, I should consult the 1994 Catechism of the Catholic Church.

However, when the Catechism contradicted earlier documents,

But this is circular reasoning by an insufficiently informed outsider. Rather than say, “I’ll see what the Catechism informs me about Catholic teaching, since the pope said it was the ‘sure norm of faith,'” this approach is more like, “I’ll continue with my [unproven] gratuitous assumption / premise that it simply contradicts earlier Catholic dogmas.” Such critics ought to be content to let Catholics work out their own dogmatic history and alleged “problems” that may arise because of it. “Difficulties” in understanding are always present in

any complex system.

As I always say, C. S. Lewis observed that “it is the rules of chess that create chess problems.” Once you believe something, or have a set of rules, sometimes there are difficulties of application. The same holds true of science as well. But those who operate by no rules are blissfully free of such difficulties.

Protestants themselves work through such quandaries (real or alleged) all the time, in relation to the biblical text. That doesn’t cause them (non-liberal ones) to ditch the infallibility of Scripture, because there are exegetical “problems” to work through. So why is it that we Catholics aren’t allowed to work through our internal belief-system and difficult dogmatic or historic questions without having to hear these accusations that we are massively self-contradictory: even to the extent of using these objections as a reason to not be Catholic?

Do we not know our own beliefs and history far more than an external critic? If someone is thoroughly familiar with a belief-system and maintains that it has logical problems that’s one thing, but to make such charges simultaneously with a profession of substantial lack of expertise, is a bit much. In any event, I accept Robin’s willingness in good faith to be corrected by his Catholic friends, where necessary.

like it did when it’s statements on religious freedom contradicted Pope Leo XIII’s earlier authoritative statements,

Precisely an example of what I was just talking about . . .

or when it incorporated into it Pope John Paul II’s private opinions on the death penalty even though such views were without precedent in earlier tradition, the Catechism becomes as much a part of the problem as the solution.

This is much ado about nothing. No contradiction is present here.

Paradoxically, by making church tradition equal to Holy Scripture, Rome ends up with a fluid concept of tradition that has the effect of devaluing the authority of tradition in practice.

. . . a bald statement without even argument, let alone examples adduced as proof, so I can hardly respond.

The problem is something that Protestantism avoids, since a Protestant who rejects his church’s past tradition can simply say he doesn’t believe the creeds anymore; however, because Roman Catholics are committed to an infallible church, they do not have that luxury and must content themselves with reinterpreting the meaning of past statements under the banner of ‘development.’

Protestants believe in development, too: just not as widely. For example, any educated Protestant will freely admit that there was much development of the Trinity and Christology in the first seven centuries. The question, therefore, becomes: how much and what sort of development is proper?

For Rome, therefore, everything is up for grabs because the interpretation of all authoritative documents is in a constant state of flux.

This is simply not true. We know what we believe. It’s all laid out in magisterial documents: quite the opposite of this description. It’s a sort of Protestant game to frequently make these sweeping charges of massive confusion in Catholic ranks, as if our problems were of the same nature as their own. Such a thing is infinitely more true of Protestant doctrinal chaos. Perhaps critics are sometimes projecting onto us their own problems: passing the buck (but illogically so).

Rome is to be applauded for her high view of tradition, but we do right to protest against her for not holding a higher view.

I think this repeated rhetoric is starting to wear a bit thin by now, since, as far as I am concerned, not a single charge has held water under scrutiny, and most redound back upon Protestantism and harm it far more than us. We never really get down to brass tacks, with a one-to-one comparison of the merits of Catholicism and Protestantism.

Too Catholic to Convert to Rome

Given the above, one reason I have not converted to Roman Catholicism is because Rome does not go far enough in the areas she claims to affirm. This may sound trite, but I believe that as a Protestant I can do a better job at being ‘catholic’ than Roman Catholics themselves. As a Protestant, I believe I can trump Roman Catholics at their own game. As Peter Leithart wrote in the Foreword to Brad Littlejohn’s book The Mercersburg Theology and the Quest for Reformed Catholicity:

I teach my theology students to be ‘because of’ theologians rather than “in spite of” theologians. God is immanent not in spite of His transcendence, but because of His transcendence. The Son became man not in spite of His sovereign Lordship, but because He is Lord, as the most dramatic expression of His absolute sovereignty. Creation does not contradict God’s nature, but expresses it.

So too with Protestant Catholicism: Protestants must learn to be catholic because they are Protestants, and vice versa.

I have no idea how to respond to this section because I don’t have the slightest idea what it

means in the first place. I won’t even try. We need to see some sort of substance and hard facts, rather than vague platitudes.

Apostolic Succession Isn’t That Important

What about Rome’s claims to have apostolic succession? Isn’t that a reason to convert? I have numerous questions about apostolic succession that would need to be satisfactorily addressed before I would be convinced that apostolic succession is even in Rome’s favour.

It is part and parcel of Protestants to reject a central tenet of Christian authority, that is discussed in the Bible itself, and was universally held among the fathers and all through Christian history till the 16th century, when Protestants denied it in order to shore up their novel and revolutionary system that couldn’t (as was the case with all heretical innovations, in particulars) be traced back through history to the apostles. I have many papers about it.

However, even if Rome is correct about this, why does it really matter since the Vatican now acknowledges that Protestants, while being outside the chain of apostolic succession, are still fellow Christian “brothers” (albeit “separated brethren”), “members of Christ’s body”, part of “Christian communions” with “access to the community of salvation” and “justified by faith”?

Well, because it is always better to possess the fullness of the faith, rather than a skeletal, bare minimum conception of it. Catholic Christianity is better than mere Christianity. Secondly, we don’t think Protestants have valid ordination; therefore, Protestants don’t possess the Eucharist, which is the central focus of Christian worship and our most profound spiritual nourishment. And they are missing out on many elements of biblical, apostolic, patristic, traditional Christianity (all of those aspects that were rejected by Protestantism).

Or again: “The children who are born into these [Protestant] Communities and who grow up believing in Christ cannot be accused of the sin involved in the separation, and the Catholic Church embraces upon them as brothers, with respect and affection.”

Yes, but that is irrelevant to competing truth claims. We are not saying that because Protestants are

Christians, they ought to remain Protestants. That would be like saying that a child should always remain a child, drinking milk, and should never grow into adulthood and eat (spiritual) meat. I’m not trying to be condescending, but this is how we regard Catholicism: as the fullness, the deepness and most advanced manifestation of Christianity.

I’m very grateful for my Protestant background, because I learned so many good things (including some things that are sadly underemphasized in practice in Catholicism). But I’ve learned much more since becoming a Catholic, and the Bible has opened up into a far richer, more in-depth source of continual wonders, and I have a much fuller understanding of many texts that we scarcely dealt with at all as Protestants.

Or again, “For men who believe in Christ and have been truly baptized are in communion with the Catholic Church even though this communion is imperfect. …even in spite of [the barriers] it remains true that all who have been justified by faith in Baptism are members of Christ’s body, and have a right to be called Christian, and so are correctly accepted as brothers by the children of the Catholic Church.” If I can have all that as a Protestant by virtue of my Trinitarian baptism (and Vatican II says I can), then why does it matter if my baptism was not performed by someone standing in the link of apostolic succession?

I just explained it. If the Eucharist is part and parcel of salvation and a vibrant spiritual life (John 6:48-58), no one ought to be without it. One mustn’t confuse the nature and purpose of ecumenical statements, with more “apologetic” or dogmatic statements. They aren’t mutually exclusive, and don’t contradict. The Church acknowledges that Protestants are Christians by virtue of baptism, trinitarianism, belief in Jesus’ death on the cross as the means of salvation, grace alone, and many other common beliefs. But we continue to assert that we possess the fullness of truth.

Hence, the Church document Dominus Iesus (2000) reaffirmed our belief that the Catholic Church is the One True Church, making statements such as the following:

16. The Lord Jesus, the only Saviour, did not only establish a simple community of disciples, but constituted the Church as a salvific mystery: he himself is in the Church and the Church is in him (cf. Jn 15:1ff.; Gal 3:28; Eph 4:15-16; Acts 9:5). Therefore, the fullness of Christ’s salvific mystery belongs also to the Church, inseparably united to her Lord. Indeed, Jesus Christ continues his presence and his work of salvation in the Church and by means of the Church (cf. Col 1:24-27), which is his body (cf. 1 Cor 12:12-13, 27; Col 1:18). . . .

The Catholic faithful are required to profess that there is an historical continuity — rooted in the apostolic succession — between the Church founded by Christ and the Catholic Church: “This is the single Church of Christ… which our Saviour, after his resurrection, entrusted to Peter’s pastoral care (cf. Jn 21:17), commissioning him and the other Apostles to extend and rule her (cf. Mt 28:18ff.), erected for all ages as ‘the pillar and mainstay of the truth’ (1 Tim 3:15). This Church, constituted and organized as a society in the present world, subsists in [subsistit in] the Catholic Church, governed by the Successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him”. With the expression subsistit in, the Second Vatican Council sought to harmonize two doctrinal statements: on the one hand, that the Church of Christ, despite the divisions which exist among Christians, continues to exist fully only in the Catholic Church, and on the other hand, that “outside of her structure, many elements can be found of sanctification and truth”, that is, in those Churches and ecclesial communities which are not yet in full communion with the Catholic Church. But with respect to these, it needs to be stated that “they derive their efficacy from the very fullness of grace and truth entrusted to the Catholic Church”.

[sections 20-22 discuss specifically the relation of the Church to salvation and reassert the traditional understanding, despite the claims from many critics that somehow the Church believes differently today about the Church’s centrality to salvation, as a human instrument ordained by God]

But I am not even convinced that apostolic succession even matters, given some of the questions I have raised about it elsewhere.

Anyone can choose to reject biblical, apostolic, patristic, traditional Christianity (even God grants them the free will to do that), but I think it is a foolish choice to make.

As for the sections at the end of the paper devoted to the arguments of so-called “traditionalist” Catholics and the criticisms therein, I do not subscribe to their views, and they depart in some ways from what the Catholic Church teaches, so I will let them defend themselves (I couldn’t defend such incoherence anyway). But just a few thoughts on a couple of things here . . .:

The current pope stated in no uncertain terms in 1985 that the authority of Trent and Vatican II rest on precisely the same basis, so that one cannot reject one without also rejecting the other.

“Traditionalists” (especially of the more radical type) are not more consistent than regular old “orthodox Catholics” like myself (whom they sometimes disdainfully call “neo-Catholics”), who accept all that the Church teaches. To the contrary, they are quite inconsistent. They want to remain Catholic, but pick and choose what doctrines they will accept and which they will reject (what we call “cafeteria Catholics”): precisely as Catholic liberals do, and like Luther when he started his revolt; and as Protestants do today. They put themselves in the driver’s seat, judging popes and councils alike with impunity, which is not what the Catholic Church teaches. It’s a liberal and Protestant notion of private judgment.

We do not say that our view is preferable to that of Orthodoxy,

simply because we say so (which indeed is logical circularity and a sort of fideism), but rather, because our view is

more in line with both the Bible and early Church history (things that can be demonstrated), and that the Orthodox interpretations, where they differ with ours, are unsustainable in light of both.

I have a web page on Orthodoxy and also a book about it, for those further interested in our replies to their contra-Catholic claims. “Holy Tradition” is shown by what the Church fathers actually believed in consensus: a thing that is demonstrable (I have a book that collects important utterances of the fathers as well).

I agree with “traditionalists” insofar as they say that Protestants are in danger of going to hell. I would argue it in a different fashion and nuance it a lot more, but it is perfectly true that if a person of any persuasion understands and knows that the Catholic Church is the One True Church and rejects it, then he is in distinct danger of hellfire: precisely because of the truth that “outside the Church is no salvation.”

Blessedly (for their sakes), among Protestants, so few truly know what the Catholic Church teaches and doesn’t teach. Therefore, what they reject is (largely) not the Church herself, but a caricature of the Church. But there is but one Church (a truth extremely clear in the New Testament) and all Christians are duty-bound to seek and find it, and not to play games with the doctrinally relative, anti-biblical, sectarian, chaotic foolishness of denominationalism.

I also think that if anyone grapples in great depth with the nature and belief-system of the early Church, and cares about Church history as part and parcel of Christianity (which was always a fundamentally historical religion), then they will eventually become either Orthodox or Catholic (or else have to ineffectively rationalize why they are Protestants). How most Protestants avoid this difficulty is to simply ignore or minimize the fathers and claim to adhere to a Bible-based faith only.

None of this involves circular logic at all, rightly understood and closely analyzed. Jesus was an actual, historical Person Whose life is recounted in infallible, inspired, inerrant Scripture. Before He rose from the dead (thus proving He was Whom He repeatedly claimed to be: God), He set up an actual, historical Church that was initially headed by Peter, and then by successors (apostolic succession being referred to and demonstrated in the Bible, and also, massive biblical indications of Petrine primacy and the papacy). It has historical continuity. The first council in Jerusalem gives us an idea of how its authority worked — with St. Paul proclaiming its decrees in his missionary journeys as binding upon all (Acts 16:4).

All we need do is identify the body that continued all this from the beginning, without departing doctrinally or morally, since we are promised that the Holy Spirit will guide the Church into all truth (John chapters 14-16) and there are various biblical indications of indefectibility. It’s not difficult to do. It’s not easy, but it’s not difficult, either, once the arguments are laid out. They are solid, and will stand up against scrutiny.

Finally, as for the relation of popes and ecumenical councils (even the earliest ones): alluded to near the end, this too, can be established on historical grounds, not dogmatic claims only (arguably circular).