vs. Reformed Baptist Elder Jim Drickamer

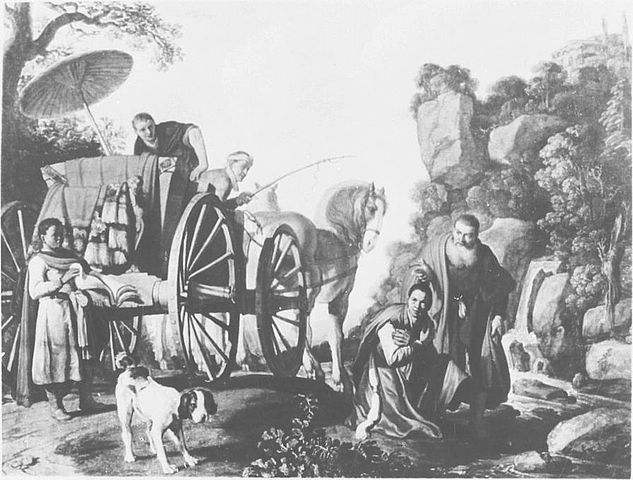

The Baptism of the Eunuch (1623), by Pieter Lastman (1583-1633) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

I am replying to Jim’s comments made underneath another blog post of mine. His words will be in blue.

*****

Well, then, how about this:

On page 32 of your book, The Catholic Verses, you ask, “Does the Bible itself teach that it can always be understood by anyone who is filled with the Holy Spirit…?” This citation comes from the part of Chapter 3 in your book where you are attempting to prove the necessity of authoritative interpretation.

After quoting Nehemiah 8:8, Acts 8:27-31, and II Peter 1:20, you wrote on the top of page 32, “Catholics hold that Scripture is a fairly clear document and able to be understood by the average reader, but also that the Church is needed to provide a doctrinal norm, an overall framework for determining proper biblical interpretation.”

We can stop at this point, because even though it is obvious that by “Church” you mean the Roman Catholic Church and specifically the papacy, you fail to prove this.

My challenge was: “find one of my innumerable papers on [sola Scriptura] and actually try to directly interact with my reasoning point-by-point.” You found one chapter of one of my 48 theological books and took up two sentences in it, then went all over the ballpark with those, as is your wont. That hardly fulfills my simple request. But at least it’s interesting enough to reply to.

Since you cite three passages that I used as my texts to comment upon, let’s bring them up (from my book), so readers can see what I was talking about in context:

THE NECESSITY OF AUTHORITATIVE INTERPRETATION

Nehemiah 8:8 [RSV]: “And they read from the book, from the law of God, clearly; and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading.” (cf. Mk 4:33-34)

Acts 8:27-31: “And he rose and went. And behold, an Ethiopian, a eunuch, a minister of the Candace, queen of the Ethiopians, in charge of all her treasure, had come to Jerusalem to worship 28 and was returning; seated in his chariot, he was reading the prophet Isaiah. 29 And the Spirit said to Philip, ‘Go up and join this chariot.’ 30 So Philip ran to him, and heard him reading Isaiah the prophet, and asked, ‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ 31 And he said, ‘How can I, unless some one guides me?’ And he invited Philip to come up and sit with him.”

2 Peter 1:20: “First of all you must understand this, that no prophecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation,” (cf. 2 Pet. 3:15-16)

A bit later, I elaborated:

The teaching authority of the Church and its necessity to preserve true doctrine and to prevent dissensions and heresies has always been a major issue between Catholics and Protestants.

Does the Bible itself teach that it can always be understood by anyone who is filled with the Holy Spirit, as Luther claims (elsewhere he claimed, famously, that even a “plowboy” could understand it)? This is not the outlook of the writers of the Old Testament. Indications are numerous:

Moses was told to teach the Hebrews the statutes and the decisions, not just read them to the people (Exod. 18:20). The Levitical priets interpreted the biblical injunctions (Deut. 17:11). The penalty for disobedience was death (Deut. 17:12, 33:10; cf. 19:16-17, 2 Chron. 15:3, 19:8-10; Mal. 2:6-8). Ezra, a priest and a scribe, taught the Jewish Law to Israel, and his authority was binding, under pain of imprisonment, banishment, loss of goods, and even death (Ezra 7:6,10, 25-26).

In Nehemiah 8:1-8, Ezra reads the Law of Moses to the people in Jerusalem (8:3). In 8:7 we find thirteen Levites who assisted Ezra, and who helped the people to understand the Law. Much earlier, in King Jehoshaphat’s reign, we find Levites exercising the same function (2 Chron. 17:8-9). There is no sola Scriptura with its associated idea of “perspicuity” here.

The two passages above from the New Testament demonstrate that this principle did not change with the New Covenant. The Apostles promulgated an authoritative tradition (see the next section), and they did not tolerate dissension from it (see the previous chapter on divisions and denominationalism). Once again, we find that an important Protestant distinctive is not biblical.

Since you ignore all of that, readers have little idea of the nature and scope of my original argument. Instead, you go off on ten other tangents: far from my subject matter. Nothing is accomplished in moving a discussion forward, by continual diversions into unrelated subject matter: the “1001 topics” or “Bible hopscotch” routine. But it’s very common for Protestants to do this, in discussion with Catholics. It’s fascinating to ponder why that is. I can only guess that it indicates less than total confidence in their own positions, or else they would be willing to defend them at length, in-depth, and with specificity: point-by-point. When one lacks confidence, one switches to another topic. That’s my theory, anyway, out of a lack of any more plausible interpretation.

even though it is obvious that by “Church” you mean the Roman Catholic Church and specifically the papacy, you fail to prove this.

Actually, I did not have that specifically in mind when bringing up these passages, but rather, whatever the universal “Church” is that is described in the New Testament: that all agree exists (see, e.g., Mt 16:18; Acts 5:11; 8:3; 9:31; 12:5; 1 Cor 10:32; 12:28; 15:9; Eph 1:22; 3:10, 21; 5:23-32 [six times]; Phil 3:6; Col 1:18, 24; 1 Tim 3:15). I was attempting to establish the authoritativeness of the New Testament Church: specifically as pertaining to Scripture interpretation. That’s an argument all Christians can enter into, without the necessity of figuring out which Church is the successor and continuation of the New Testament Church (a completely separate and distinct historical discussion).

The Old Testament arguments provide the analogy of the Jewish structure of authority (Moses, the levitical priests, and Ezra the scribe). Then I show how the same state of affairs carries into the new covenant and the Christian Church:

Acts 8:31 . . . How can I [understand Scripture], unless some one guides me? . . .

2 Peter 1:20 . . . no prophecy of scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation,

But instead of dealing with that very specific, laid-out argument from Scripture, you immediately take the discussion down the rabbit trail of “which Church today is the continuation of the Church in Scripture?” This removes from you the responsibility of defending the novel assertions of Protestantism regarding the perspicuity (clearness) of Scripture.

Martin Luther is reputed to have said in his debate with Johann Eck in Leipzig in 1519: “The plough-boy with scripture is mightier than the greatest Pope without.” (source)

And he wrote in his 1525 work, The Bondage of the Will, in its sections on the clarity of Scripture, and in his comments about “schoolboys,” etc. understanding Scripture:

He says in Isaiah “My counsel shall stand “and my will shall be brought to pass. (Isa. xlvi. 10.) Is there any schoolboy who does not understand what is meant by these words (counsel, will, brought to pass, stand)? (Part I; section xi; p. 36 in Edward Thomas Vaughan translation, 1823; my emphasis)

You are looking for a knot in a bulrush. These expressions do not make Scripture obscure, or such as must be modulated according to the varieties of the hearer; except that some people are fond of making obscurities where there are none. These are matters of grammar: the sentiment is expressed in figurative words; but those, such as even schoolboys understand. How ever, we are talking about doctrines, not about figures of speech, in this cause of ours. (Part I; section xxv; p. 77 in Vaughan translation; my emphasis)

This is the contrast I was dealing with in that section of that chapter: authoritative Church interpretation vs. Luther’s and Protestants’ notions that any plowboy or schoolboy can easily understand Scripture: even better than popes. Our view is easily demonstrated from Holy Scripture itself; Luther’s was pulled out of a hat . . .

If you have read this far, you are probably ready to yell at me for dismissing out of hand the history of the Roman Catholic Church, the legacy of Peter, and so on.

Your mistake was not in dismissing it, but in bringing it up! I have noted that bringing that up is irrelevant to the discussion at hand. This is a scriptural argument, not historical.

You almost certainly believe that the Roman Catholic Church is the one Christ said He will build in Matthew 16.

Indeed I do. Not the topic at hand . . .

I must seem like an idiot to you.

No; you seem like a typical Reformed Baptist elder or pastor: well-acquainted with Scripture, and pious and desiring to follow God and to do His will, but burdened by all the usual false and unbiblical premises that Protestants labor under. The house is only as good as its foundation is stable and strong.

Perhaps I am, but what I would like to focus on for a few minutes is the idea of a human, authoritative interpreter of Scripture. Is such a person really necessary?

Yes, in the overall picture; not for every Bible verse, but to maintain an overall structure of orthodoxy and unity of doctrine.

You refer to several Bible passages in which some people were assigned the task of teaching others the word of God, including interpreting that word to them and showing them how to apply it to their lives. But were those teachers authoritative?

Yes. Philip and Peter were apostles.

Of course, before that question can be answered, the term, “authoritative,” must be defined, something you don’t do in your book.

The final say . . .

It is self-evident that these individuals who were sent to teach were authoritative in that they had the authority to teach. But what did they have the authority to teach?

The gospel, or tradition, or Word of God, which are all synonymous concepts, as I illustrated in my first book (completed in 1996), A Biblical Defense of Catholicism (pp. 12-13):

Tradition, Gospel, and Word of God are Synonymous

It is obvious from the above biblical data that the concepts of Tradition, Gospel, and Word of God (as well as other terms) are essentially synonymous. All are predominantly oral, and all are referred to as being delivered and received:

1 Corinthians 11:2 . . . maintain the traditions . . . . even as I have delivered them to you.

2 Thessalonians 2:15 . . . hold to the traditions . . . . taught . . . by word of mouth or by letter.

2 Thessalonians 3:6 . . . the tradition that you received from us.

1 Corinthians 15:1 . . . the gospel, which you received . . .

Galatians 1:9 . . . the gospel . . . which you received.

1 Thessalonians 2:9 . . . we preached to you the gospel of God.

Acts 8:14 . . . Samaria had received the word of God . . .

1 Thessalonians 2:13 . . . you received the word of God, which you heard from us, . . .

2 Peter 2:21 . . . the holy commandment delivered to them.

Jude 3 . . . the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints.

In St. Paul’s two letters to the Thessalonians alone we see that three of the above terms are used interchangeably. Clearly then, tradition is not a dirty word in the Bible, particularly for St. Paul. If, on the other hand, one wants to maintain that it is, then Gospel and Word of God are also bad words! Thus, the commonly-asserted dichotomy between the gospel and Tradition, or between the Bible and Tradition is unbiblical itself and must be discarded by the truly biblically-minded person as (quite ironically) a corrupt tradition of men.

More to the point here, did they have the authority to teach whatever they wanted? Did they have the authority to interpret what they were teaching anyway they chose, or to apply it anyway they thought best?

Of course not. They received what they were to teach from God’s inspired prophets and apostles. They were to teach the same things the prophets and apostles taught. They did not have authority to add to God’s word received from the prophets and apostles, to subtract from His word, or in any other way to change it. If they did change it, they became false teachers and according to the Mosaic Law should have been stoned to death.

We can see this also in the New Testament.

Christ commanded His disciples in Matthew 28: 19-20 to “teach them to observe whatsoever I have commanded you.” The disciples had authority to teach but not to go beyond what Christ commanded to be taught.

In the same way in II Thessalonians 2: 15, Paul commands disciples to stand firm in and hold fast to the traditions they received from “us,” from the apostles. Again, believers are obligated to stand and hold, not just any tradition and not every tradition but the traditions received from the apostles.

We have no disagreement on any of this. It’s because sola Scriptura departs from Scripture and apostolic teaching, that we reject it, and why Christianity never taught it until Luther invented it in the 16th century, under pressure to defend his goofy heretical ideas.

If it is necessary for there to be a human, authoritative interpreter, then it is also necessary for that human, authoritative interpreter to limit what he teaches to the things commanded by Christ and the traditions received from the apostles. If he goes beyond those restrictions, then he is a false teacher. And if he teaches as Gospel anything different from the Gospel proclaimed by Christ and His apostles, then as Paul writes in Galatians 1, he falls under the anathema of God.

We also have here a test that can be used to determine if the Roman Catholic Church or any Christian church is the one or, at least, part of the one Christ said He will build. That test is an examination of what a church teaches. We should be able to ask of it, “Did Christ command that doctrine to be taught?” and, “Did that tradition come from the apostles?”

Agreed again. You seem to think that the Catholic Church would oppose all these notions, but it does not. These are not the issues. The issue, as we see it, is the Protestant denial of an infallible / authoritative Church and an infallible / authoritative apostolic tradition. This denial is part and parcel of the nature of sola Scriptura, which proclaims that only Scripture is infallible and a “final authority.”

This brings us to Sola Scriptura.

It is obvious that Christ and the prophets and apostles taught orally first. Their oral teachings were the word of God. But this is an extraordinary circumstance that is not normative.

That is, Christ has already died, risen, and ascended. All of the prophets and apostles have already died. There is no one still living who heard the oral teaching of any of them. So how can we know what they taught orally?

One answer to that question is we can infer what they taught orally from the content of their writings, the Scriptures.

But the question persists as to whether or not there is some content to be taught in the church which was only taught orally by Jesus, prophets, and apostles and never written down.

More to the point here, how can it be proven that something was taught orally by Jesus, prophets, or apostles if it was never written down? Was it commanded by Christ to be taught? Was it a tradition received from the apostles?

If it is something taught in Scripture, then we can know it came from Christ, from the apostles. If not, the question is still open. How can we know?

We know by the fact that certain teachings become widespread in the early Church; become the consensus of the Church fathers. Such things as apostolic succession, infant baptism, regional bishops, the Real Presence in the Eucharist, intercession of the saints, the papacy, baptismal regeneration, the sinlessness of Mary, were all developed in the early Church, and all claimed to have been received from the apostles. On the other hand, Protestant distinctives cannot be found in the Church fathers, as I have shown innumerable times in debates with Protestants about the Church fathers.

If you want to see authoritative scriptural interpretation by the Church in the New Testament, go to the Jerusalem council (Acts 15). Here was a council of not just apostles, but also elders. They got together and made a decision regarding circumcision: a thing that the Old Testament never discussed (it taught the opposite), or that was never suggested by Jesus: that Gentile converts to Christianity need not be circumcised. It appealed to the guidance of the Holy Spirit (15:28). It’s teachings were binding upon all Christians in different areas, and were proclaimed by St. Paul in his missionary journeys (16:4).

That is “Catholic authority” (even conciliar authority) and authoritative biblical interpretation; it is not Protestant sola Scriptura, by any stretch of the imagination. It couldn’t be more different from Protestant thinking than it is.