The careful reader will note something forlorn in the words “Pope Francis presided over the canonizations…before a congregation of tens of thousands of people.” Josemaria Escriva’s canonization drew a crowd of 300,000 – and his popularity was, as everyone knows, far from universal. By St. Peter’s Square standards, “tens of thousands” just doesn’t add up to that big a crowd, especially not for a doubleheader.

Yet there’s a sad logic behind the slim numbers. The two new saints whom Pope Francis raised to the altars on May 17 represent a small and shrinking constituency. Both of them — Mariam Baouardy and Marie Alphonsine Danil Ghattas – were Arab Christians.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War, the world’s eyes have turned toward those Christians driven from historic, sometimes ancient, communities by various groups of Sunni Muslim extremists, including the Islamic State, whose rampages have reached into Iraq. According to reliable estimates, approximately two-thirds of Iraq’s Christians, and two-thirds of Syria’s Christians, have fled abroad, to save their lives.

But in fact, Christians were quitting the land of the Bible – and the cradle of civilization – even when the region was relatively stable. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the Christian share of the Middle East’s population has dropped from 20 to five. Although these figures do, in part, reflect relatively high Muslim birth rates, they also point to Christian flight, which Center for American Progress credits to “violence, oppression, and lack of economic opportunities going back decades.”

Pope Francis has made a priority of calling attention to this imperiled and dwindling group. Last November during an official visit to Istanbul, he and Orthodox Patriarch Bartholomew issued a joint declaration that included the statement: “We are not resigned to a Middle East without Christians.” Canonizing two women from Ottoman Palestine was a timely move – a reminder that Christian roots in the region run deep.

These two new saints look well chosen to deliver the message. One, Mariam Baouardy, belonged to the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. For centuries a patriarchate made up of Arabic-speaking Orthodox Christians, the Melkites returned to communion with Rome in 1729. Today’s Melkites are spread throughout the Middle East; as recently as 2008, Syria was home to the largest single concentration. By raising Mariam Baouardy to the altars, the Vatican is offering hope and inspiration to those who need it most.

With their lives, the new saints offer examples of how Christians can live gracefully and productively in Muslim-majority nations. Both contemplatives were better known for ecstatic visions than political agitation. Mariam Baouardy founded a Discalced Carmelite convent in Bethlehem – the first in Palestine; Marie-Alphonsine Danil Ghattas founded the Sisters of the Rosary. Neither act would look provocative in the eyes of any but the most bigoted Muslims. Before entering religious life, Mariam Baouardy did survive a sword cut to the throat courtesy of a spurned suitor who had also tried to convert her to Islam, but this was a one-off, and the episode does not appear in the Catholic News Association’s press release on her.

Living gracefully and productively as a Christian minority in a Muslim-majority nation is no easy thing. I learned this through conversation with a Jordanian priest – a Melkite, in fact. One member of our group suggested he was betraying the Great Commission by not proselytizing openly. The priest replied – with thinning patience, it seemed to me – that, simply by living the Gospel and exemplifying Christian virtue in his daily life, he was doing his job just fine. Unsurprisingly, he did not compare his position to that of a fiddler on the roof, but he left me with the impression that it was a apt metaphor.

To a point, the Vatican’s message seems to have taken. By waving Palestinian flags, the crowd in St. Peter’s, small though it was, claimed the new saints for a living political entity, or at any rate a nascent one. By attending the ceremony in person, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas solemnized the claim.

Yet a Middle East without Christians remains a very real possibility. When Francis and Bartholomew were meeting in Istanbul, I was living just across the Sea of Marmara, in a village called Görükle. The name has no meaning in Turkish. It’s a corruption of Kouvoukleia, the name it held in Ottoman times, when the majority of its inhabitants were Greek-speaking Christians. One winter’s night, I decided to hunt for the ruins of St. George’s Orthodox Church, which, according to the memoir of Olympia Rizidis, daughter of Kouvokleia Greeks, had once stood in the center of town.

For my interpreter and guide, I took along a fellow teacher named Settar. Locals pointed us to a worn marble foundation from the middle of which grew a çeşme, or public drinking foundation. Carved into it were the words: Kilise Çeşmesi. The church drinking fountain.

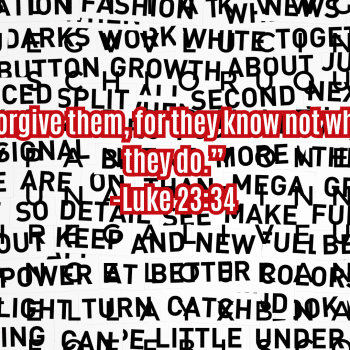

Erasing communal memory really is that easy. Knock down a church, build a fountain. In 90 years, who will know the difference? Fashioning a death-mask of Middle Eastern Christianity was probably the last thing Francis meant to do when he canonized these two Palestinian nuns, but that’s how it could end up looking through the eyes of history. In that event, two extra saints on the Vatican honor rolls will make a better tribute to recent Arab Christian civilization than none at all.