![By RassaphoreGeorge (Parastas in Cemetary.jpg) [CC by 1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en)] via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/721/2016/07/Parastas_in_Cemetery-1024x742.jpg)

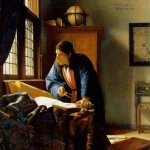

We had planned this parastas last week. I had first suggested it to my priest because a few of my close friends had asked me to pray for their families. Apart from one Latin Catholic who asked us to pray for her father who recently reposed, many of my friends – even though I have become Eastern Catholic – are evangelicals, and the people we prayed for were, for the most part, evangelical Protestants: a friend’s mother-in-law, another’s classmate, still another’s pastor, and more in another’s extended family. Though many of us are not in communion, there are no boundaries for praying for the souls of those who have reposed.

Yesterday morning, we woke up and learned of what had happened in Normandy – how Islamic State sympathizers had stormed the threshold of a church during morning mass, slit the throat of the celebrant Fr Jacques Hamel, and used some of the small group of mass attendees as human shields until they were dispatched by the police. As the Church with the world, we were horrified. Jean Duchesne – the Archbishop of Paris’s special advisor – writes starkly, ‘Until now…the fanatics had attacked aspects of the flattering self-image that we “citizens” have of ourselves’ (like Charlie Hebdo, the French National Stadium, the Bataclan, the Eleventh Arrondissement, Bastille Day), but this time, the ‘target of this revenge was the root of the West, the West’s living source, even when it is unremembered – namely, Christianity, in the time and the place where, tacitly but invincibly, it becomes most explicitly and intensely real: the celebration of the Mass.’ Mary Pezzulo is therefore right when she cautions against jumping to the celebration of martyrdom here: ‘This is a tragedy and a trauma, and people who try to make it out to be nothing but a cause for celebration are wrong. Terrorist attacks are always a failure of humanity. We should always be traumatized. We should always weep.’

Radically, then, the parastas positions every death in relation to the martyrs. The extended conclusion of the service is called the Canon of the Departed, and in each of the odes that compose it, we hear of the solidarity of the martyrs with the reposed. In the first ode, we listen to the martyrs interceding for the reposed: ‘Your courageous martyrs,’ the first ode reads, ‘in their heavenly mansions implore You, O Lord: Deem the faithful, whom You have taken from the earth, worthy to receive Your eternal blessings.’ The same goes for the third ode: ‘Your martyrs, O Giver of Life, have competed according to the rules and were rewarded with the laurel of victory, now they ask of You eternal redemption for the earnestly praying faithful ones who have departed from us.’

The sixth ode explains this invocation of the martyrs by identifying them with the sufferings of Christ on the cross: ‘While being nailed to the Cross, O Blessed One, You gathered to Yourself throngs of martyrs who imitated Your passion; therefore we beseech You, give rest to them who have now departed to You.’ The ninth ode teaches that the reposed imitate the martyrs: ‘Hope encouraged the multitude of martyrs and directed them in fervour to Your love, and it foreshadowed the future and truly undisturbed rest. O Gracious One, grant that Your departed faithful may attain the same rest.’

At one point while we were singing through this canon, our priest paused to make a reflection. It is not at every parastas that we remember those who have died in our time in odium fidei, as the Latins say. But on the very day of our parastas, Père Jacques had received the culmination of a long life (as another colleague also noted) – the crown of martyrdom, his blood spilled upon the very altar where Christ’s blood is poured out for us.

The parastas is thus supposed to remind us that every death is a shock. But to say it like that would almost be to slip into an #AllLivesMatter key, to throw a glib Valar morghulis in dismissal of all the departed. The horror of such triviality, as my parish priest often reminds us, is that it is a ‘détente with death,’ a numb acceptance that death is final and even a fine end to a celebrated life.

The blood of the martyrs, in connection with the blood of Christ spilled by the principalities and powers of this age, awakens us from our numbness. Yes, the martyrs bear witness (as the odes say) to the hope of the resurrection, but their bodies also fully display the profound evil manifested by those who, motivated by ideology of any kind, perpetrate the horror of death. It is enough that death is horrible. How much worse it is when this horror is purposefully brought about by a deliberate act. Perhaps this is why G-d commands his people in the Decalogue: ‘You shall not kill.’

Including Père Jacques in our parastas brought us from the ideal conception of martyrdom to its horrific concrete reality. It is not fine that he died the way he did, and therefore, it is also not fine that my friends’ mother-in-law, father, pastor, classmate, and extended families died. By all accounts, Père Jacques was sundered from his community by death; my friends are also stricken with grief because their loved ones have been sundered from them. The pain of Père Jacques and his parish is our pain; the pain of death experienced by my Protestant friends is also our church’s to share. None of it is the way it should be; we grieve because it is the way that things currently stand.

‘Break your contract with death!’ our priest once exhorted during a homily a few months back. He did not have to repeat it at our service, as the parastas conveyed the same message. When the Canon speaks of the solidarity of the martyrs in Christ with the reposed, does this not presume, as our Lord tells the Sadducees, that ‘He is not God of the dead, but of the living’ (Matt. 22.32)? This is the blessed hope, Metropolitan John of Pergamon reminds us, of belonging to the Church, of having an ‘ecclesial mode of existence,’ because in a ‘hypostasis’ of ‘communion and love,’

the body transcends together with its individualism and separation from other beings even its own dissolution, which is death. Since it has been shown as a body of communion to be free from the laws of its biological nature with regard to individualism and exclusiveness, why should it not also be shown finally to be free even from the very laws relating to death, which are only the other side of the same coin? The ecclesial existence of man, his hypostasization in a eucharistic manner, thus constitutes a pledge, an “earnest,” of the final victory of man over death. This victory will be a victory not of nature but of the person, and consequently not a victory of man in his self-sufficency but of man in his hypostatic union with God, that is, a victory of God as the man of patristic Christology. (Zizioulas, Being as Communion: Studies in Personhood and the Church, p. 64).

‘Christ is risen from the dead,’ we thus sing at Pascha, ‘trampling death by death, and to those in the tombs giving life.’ We proclaim in the Hymn of St Athanasius of Alexandria at every Divine Liturgy: ‘You were crucified, O Christ our God, and trampled death by death.’ Even more pointedly, the parastas invokes the martyrs, the ones who died the most horribly, to trample death as they intercede for all the reposed. Death makes no sense, but the ones who died the most senseless of all deaths – death perpetrated by persons possessed by ideology – triumph over the horror by participating in the destruction of death itself. Therefore, just as the martyrs interceded for Père Jacques at his martyrdom, so by including him in our parastas, he too intercedes together with the martyrs (as the parastas teaches) for all the reposed we remembered as we prayed. Together, they behold the Lord’s face, and the Crucified One wipes away their tears with his pierced hand.

Like the thief who called to Christ on the cross asking to be remembered when the Lord comes into his kingdom, we finished the parastas asking that the Lord will make their memory to be eternal.

Eternal memory! Eternal memory! Eternal memory!

Eternal memory! Eternal memory! Eternal memory!

With the saints, give them rest, O Christ!

Eternal memory!