I first heard the term on television. There, news reporters were prattling on about these two words sexual harassment and what it meant for our culture, which probably was the first time I had ever heard that word too. I was not sure what that second word was either, and I did not know that I’d grow up to be a cultural geographer, and I think the explanation I received was about as good as how sexual harassment was explained to me, which was probably surprisingly good given my age but did more to muddle the problem than shed light on it.

In my recollection (which may be faulty, but the stakes for this memory are much lower than for those before the Senate Judiciary Committee next week), I was asked what I understood the term to mean. I suppose that this quasi-Socratic method is effective for people who think that you already know everything from your soul being immortal, but the truth is that if I had known it even from a past life, I couldn’t remember it. All I could understand was that sex on an official form was usually divided between two letters, M and F. M meant that you were a man, and F somehow stood for woman, but I could not understand why it was not W. In any case, the person who explained it to me – and I think it was my mom, but I cannot be certain – told me in Cantonese that it as when an M might hah an F. Hah in Cantonese has the connotation of bullying, but that is a much too mild translation, because it is not only physical, but involves a kind of psychological gaslighting, as mind games often accompany the physical acts of violence. Looking back, that was a pretty good explanation because both elements compose a lot of what sexual harassment is, but I could not understand then why on television, the public service announcements about sexual harassment always featured men seeming to compliment women on their beauty. They all sounded nice, probably because they were all aired on public television, so I decided that I was probably too young to understand how it was that a compliment could be construed as the act of hah. It sounded really bad in a very complicated way, and that complication was probably where the badness lay, I figured.

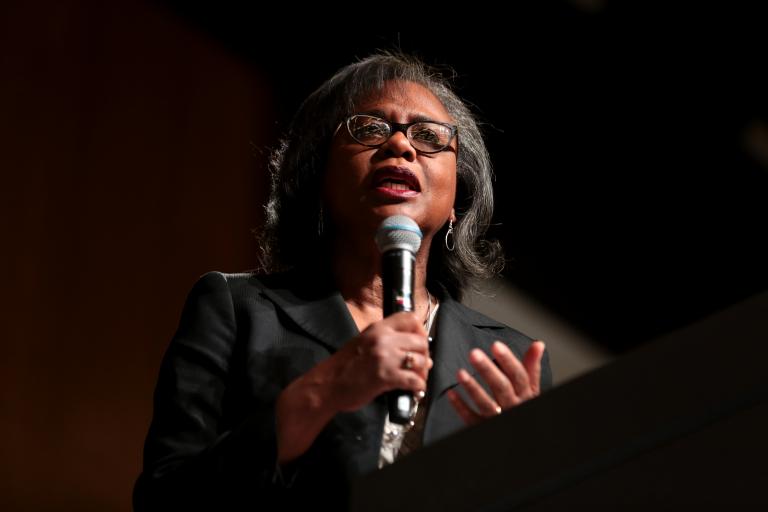

I now understand that I had been living through the time marked by the Senate hearings concerning Anita Hill, with reference to the sexual harassment perpetrated against her by now-Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. When I speak to colleagues and friends about this case, I admit that I am a bit embarrassed because many of them tend to be older, wiser, and more experienced than me – even while treating me as their peer – and have a distinct memory of the kind of gaslighting Anita Hill endured by a judiciary committee formed entirely by white men questioning her. At the time, I was still trying to figure out what sex was, what it had to do with bullying, and how it actually worked, which was difficult given the insufficient data with which I had to work. Fortunately for me, the nineties were replete with these kinds of stories – the Polly Klaas and JonBenet murders, the O.J. Simpson trial, all the women that Bill Clinton did not have sexual relations with (only inappropriate ones lol), and on and on – so eventually, I got the hang of it and figured it out. In fact, I suppose I had to figure it out because my own childhood church, one located in Hayward, California that is not unknown in the larger world of Chinese evangelicalism, fell apart in the nineties because of a sex scandal. My father was the last one standing among the clergy there in terms of having clean hands and had to handle it, with the help of a pastor from another church who was then working in a popular parachurch organization who had walked in on two of his pastoral colleagues copulating. Eventually, given the spate of sex scandals that plagued Chinese evangelical churches in the nineties, my father took it upon himself to write a Doctor of Ministry dissertation on pastoral sexual misconduct in Chinese churches, which I had the dubious honour of turning into prose from his notes. In this way, I have an unofficial doctorate by osmosis in these kinds of things now that will never be listed in my curriculum vitae, which is a far cry from my sexual ignorance when I was five.

I say all of this now because the upcoming hearings that have been instigated by the revelation that Christine Blasey Ford is the one who has been accusing Brett Kavanaugh of attempting to rape her in high school involves a dimension that I do not think has been well-discussed. This omission also parallels the Anita Hill allegations against Clarence Thomas, and of all people, only Rachel Maddow has seemed to pick up on it, albeit obliquely. That there is a parallel between Ford and Hill is only unclear to those who are blind; even Anita Hill has written an op-ed to the New York Times talking about them.

Maddow picks up on the theme of family in the Anita Hill hearings. After Hill introduces herself, her entire family walks in to the chambers, and it is, in Hill’s words, ‘a very large family.’ Her mother and father are seated behind her, and Maddow plays a previously unaired clip – which is why Maddow really is the one breaking this story, as she tells her views that it was she who unearthed the clip – that the single hardest thing during the hearings was that just as her parents must have felt helpless that they could not protect her from what she experienced, she could not protect them from now hearing about it in her testimony. Hill elaborates in that clip that this was devastating because African Americans tend to be suspicious of the government in the first place, but to have that suspicion ‘personalized’ in a way that undermined one’s entire philosophy of life in which integrity and telling the truth and working hard are the pillars on which one builds a solid life must be unnerving. Hill credits her parents with being ‘strong.’ I think that that is an understatement.

But as Hill continues in her testimony, these practices of integrity were part and parcel of a larger structure in which her family was embedded, the ‘black Baptist church,’ which she says in her statement still plays an important role in her life. Certainly, this is not the place for me to bring in the convergences of my own life story with the black Baptist church in very profound ways that have shaped my life and vocation, but it does remind me a bit of what the Protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer said about the state of the church in America when he visited in the 1930s and ended up going regularly to the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. The gist of his commentary is that the black church is basically the true church in America because its very existence tells the truth about the state of race relations in this country, that for all the pretending that white Americans do when it comes to the racial hierarchy that survived and became even more perverse after the Emancipation, they were still the source of racial oppression, and this could be seen in the way that churches themselves were segregated. At one level, Hill’s testimony in front of a bunch of white men in the Senate Judiciary Committee is a picture of this phenomenon still playing out in the early 1990s, that it takes a woman from the black church – indeed, the true church, to use Bonhoeffer’s terms – to confront the perverse pretentiousness of white men whose smirks at her testimony reveal that they really think that boys will be boys.

We must not forget, then, to go one level deeper. Certainly, Hill was faced in the chambers by a bunch of white men, but she was accusing a black man, Clarence Thomas, of sexually harassing her. Thomas, it must be noted, never seems to have been part of the black church in any meaningful way; if anything, his educational credentials and church involvement indicate a much more Catholic influence (again paralleling Kavanaugh, which I will get to in a bit). Yet the testimony of black women seems to indicate that if there is sexual danger to be had in their experience, it comes from within their communities in a much more personal way. Just yesterday, the Los Angeles Times reported on a small group of black women pastors coming together to talk about their experiences of sexual harassment within the black church, with famous black male preachers on the top of their mental list of predators. The writings of James Baldwin about sex in the black church as far back as Go, Tell It on the Mountain relate similar experiences, and of all the themes that his spiritual daughters Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and Maya Angelou have taken up with gusto, it is these too, so much that there is even a term to capture the experience and the imperative to be liberated from it: womanism. So too, who can forget the ugly scene in which Ariana Grande, fresh from proclaiming that God is a woman in terms of a release of feminine power over the fictions of patriarchy, was publicly groped by a black preacher at Aretha Franklin’s funeral? If the phenomenon of transference might be taken seriously, who is to say that Clarence Thomas did not transfer his missing experiences of the black church to Anita Hill, who has known that world vividly throughout her life, and then justify it by thinking it was fine precisely because of that? In other words, if sex crimes are being so vividly reported in secular society now, what’s not to say that the place to find it the most concentrated is in the church?

Here, we might visit Ford’s accusations more carefully, especially given the context that has been given to us about it. The attempted rape in this case took place at a party with members of Georgetown Prep, a Jesuit high school that Kavanaugh’s classmate Mark Judge has described as a hotbed of alcoholism and sexual chaos well into the 1980s. As a conservative commentator, Judge seems to have gotten it into his head that, like many other conservative commentators discussing the sex abuse crisis in the Latin Church, the problem seems to be gay priests forming a lavender mafia. My comments on the matter have hopefully been more circumspect, writing as I have on a friend of mine who is himself a gay priest. My view on Judge’s comments is that, at least in the words of Sirius Black to Severus Snape in the movie version of The Prisoner of Azkaban, once again he has put his keen and penetrating mind to the task and as usual come to the wrong conclusion. I would say the same about the other conservative commentators who have been trying to make sense of the unchastity in the Latin Church. Homosexual desire has nothing to do with whether one becomes an alcoholic, rapes people, or traffics them. However, a bad ecclesiology that enables them might exacerbate all three.

Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations against Brett Kavanaugh strike at the heart of the current crisis of the Latin Church with regards to sexual abuse. Here, the Latin Church, along with its Protestant allies (which reinforces that Western Christianity is much more united than the fragmented front they present to the world), has moved from pro-life victory to contraceptive triumph in the judiciary system, and Kavanaugh has been one of their champions. I am, of course, as pro-life as the rest of my Catholic sisters and brothers in all the churches we have in communion with each other for reasons both moral and mystical (the latter of which involves a process of testing the spirits in which I am still engaged, so it’s in the works, as they say), and because of that, I am not very sure that I do not feel just a bit of resentment at being sucked into the vortex of this foolishness, even though I am in a different sui juris church from these fools (I take great solace in the fact that we have many in our own church too). The central node of this idiocy, it seems to me, has been the positioning of our churches as somehow moral high grounds standing up for right and wrong when the truth of the matter for anyone who has any experience in Catholicism is that everyday life resembles much more what Artur Rosman used to call Rabelaisian Catholicism, the visceral gut-level humor of people who are more perverse than those outside the church unexpectedly being channels of grace despite themselves. The higher that kind of thing is positioned, the harder the fall.

Kavanaugh, it seems to me, was formed in the Catholic milieu that brought about the crisis that we now have, especially in the mindset that boys will be boys, which somehow inexplicably sanctions alcoholism, rape, pornography, and trafficking. Just as the receipts are coming in for the Bonhoefferian true church of the black church, so they are also arriving for the ekklesia that has styled itself as the True Church for some time, the problematic designation that gets to another one of my Eastern Catholic resentments – the framing of our people as uniates. It turns out that the sex abuse crisis that is tearing up the Latin Church is not really about homosexuality, and Ford’s allegations make that exceedingly clear in her description of the unchastity of alcohol abuse and heterosexual rape. The moral failure here is clear. Whatever the objective arguments about moral theology may be, the Church’s current ideological advocacy – that is, its stances about public policy concerning sexual morality, and therefore not the moral questions themselves – against abortion, contraception, same-sex marriage, and transgender rights depend on an assumption that ordinary people, given enough personal discipline, will be able to restrain themselves with chastity. But those in the institutions of the Church have not been practicing that very discipline, and the result is that people like Kavanaugh (and Judge) for that matter were educated to think that they could get away with rape in the context of a Catholic school. The boys will be boys moniker give the lie to the thinking that the Latin Church’s problem is homosexuality. Straight men, it turns out in this case, are the real problem.

With the newest development in the Kavanaugh hearings, the Latin Church’s sex abuse crisis have arguably gone from an ecclesial emergency to a much more universal one. At one level, it brings the sexual culture of the Latin Church of the last half century into stark public relief, exposing the contradictions between its ideological stances on morality (again, whatever the merits of the objective moral theological arguments themselves may be) and the practices that have taken place within its institutions. At another level, it also elevates the problem of churches themselves being hotbeds for sex crimes and harassment, that just as the Latin Church has had this problem, so too has the black church, and arguably also the evangelical organizations with which Boz Tchividjian has left no stone unturned as well as the Orthodox who may look so smug at their western sisters and brothers in crisis. At a third level, the universality of this problem across churches and even in secular institutions like schools, the market (who can forget that time Dominique Strauss-Kahn raped his hotel maid?), and the political arenas of governance suggests that the critical genealogy of secularization documented in the recently scholarly literature on the subject is basically correct. In that body of academic work with figures like Charles Taylor, John Milbank, Talal Asad, and Gil Anidjar (if you will humor me) as its main avatars (and with reference to Henri de Lubac, Michel de Certeau, and Ivan Illich), secularization is simply the fragmentation of political, economic, and social institutions from the centralization of the Latin Church in the tenth century. In this way, the problems of Roman Catholicism with regards to organizational structure, sexual unchastity, financial impropriety, and mind-game gaslighting politics are simply carried over to western institutions derived from it: Protestantism, academia, the medical industry, secular governance, the public sphere of civil society, and so on and so forth.

Perhaps in this way, we might think of Anita Hill as the vanguard of a postsecular impulse, with Christine Blasey Ford now as a reluctant figure at the helm of this charge now. The best explanation that I have heard of what the postsecular might be, after all the academic controversy that the term has provoked, is that it is the bubbling-up of phenomena at the cracks of everyday life that challenge the secular norms of civil society and the institutions of governance. One of those norms, it seems, is that boys will be boys, and what is challenging it is the public articulation of the visceral experience of women whose bodies are constantly threatened by that order. The real problem with this boys will be boys sentiments is not unlike the Latin Church’s problem of being a church of all bishops and no people; in this patriarchal formulation, it is that a society secularized from the Latin Church is one of all boys and no one else. The problem is not just a lack of chastity; it is that boys have long been excused from the disciplines of chaste living with regards to their bodies. Such patriarchal unchastity leaves lots of skeletons in their closets, and it turns out that those victims have flesh too. In turn, with all the connections that might be made both in terms of concrete claims and psychological transference, this postsecular moment is right to lay their charges down at the doors of the churches. After all, as the Holy Chief Apostle Peter himself put it, judgment begins in the house of God.