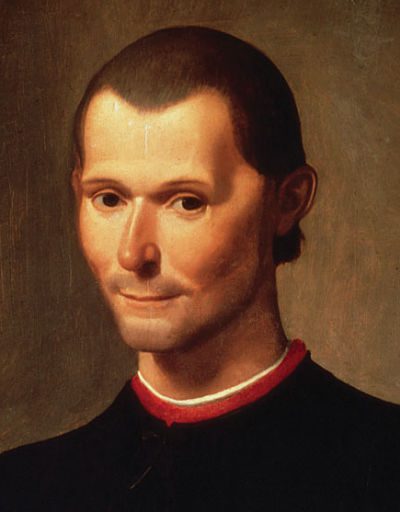

Just as Malory was ending, Machiavelli was beginning and that is as good a summary as any about the choices in politics. Where Malory ends, Machiavelli begins, but a stable body politic will have both.

Just as Malory was ending, Machiavelli was beginning and that is as good a summary as any about the choices in politics. Where Malory ends, Machiavelli begins, but a stable body politic will have both.

Too often we dismiss Malory as a mere dreamer of a golden age, of Arthur and Camelot, while Machiavelli is a man of the present, practicing real statesmanship in a broken world. The romantic fails to see his work in context and condemns the Italian as a wicked man. The tyrant uses Machiavelli as an excuse for evil, forgetting his Christian context, while the libertine longs for the romantic apocalypse that Malory warns against.

It is easy to hope for doom from the comforts of American life and it is easier still for a wicked man to justify wickedness by the hard deeds good men have had to do. This is to profoundly misunderstand both Malory and Machiavelli.

The chief works of these two writers (The Morte d’Arthur and The Prince) do two different, but necessary jobs. A state needs both a unifying myth and political unity: we need the music and the marching orders for a culture. Both the music and marching orders will deal with a broken world: Arthur will die and even a good prince must do hard things to rule.

Malory: Man to Revive the Dream

Malory lived in a civil war, the War of the Roses, but not one that threatened to divide England politically. Factions fought for the Crown and Malory appears to have played both sides. In any case, the mess of politics was not that England was falling to pieces, but that her great lords threatened to wear out the unified garment. England needed to be reminded of who she was, she needed a myth and the ability to hope until a prince could end the wars.

Malory was a practical (maybe even roguish) man of political affairs, but he created a myth to inspire Britains to a better way. Malory gave England a founding myth at a time when internal strife was making men lose hope. England was still whole, but the struggles of the War of the Roses was marring her in the minds of many.

Machiavelli: We know what is needed! Do it! Somebody?

Machiavelli strove to give Italy political unity when the myth already was present. Italy was resplendent with Italian culture, historic memory, and legends, but Italy had been politically fractured for centuries. The reasons for unity were obvious, the story did not even need to be retold (who could better than Dante?), but finding the practical man of affairs to achieve Italian unity was harder.

Saying “I have a dream. . . ” takes a great man, but incarnating that dream takes a greater one. This is why we honor Augustus more than later Roman Emperors. He took Virgil’s vision of Rome and brought about a Pax Romana, a principality of laws, that built a reality on the dreams of the Roman Republic and her mythic past. Virgil was Rome’s Malory, but in Augustus he found a greater Prince than Machiavelli could find in the city-states of Italy.

Machiavelli was a practical politician in Catholic Italy. He did not need a founding myth, the Romans, pagan and Catholic, had built great monuments in stone to Roman ideas. This founding myth is easy to take for granted, but a love for Italy and all that is Italian undergirds the practical advice Machiavelli gives:

This opportunity, therefore, ought not to be allowed to pass for letting Italy at last see her liberator appear. Nor can one express the love with which he would be received in all those provinces which have suffered so much from these foreign scourings, with what thirst for revenge, with what stubborn faith, with what devotion, with what tears. What door would be closed to him? Who would refuse obedience to him? What envy would hinder him? What Italian would refuse him homage? To all of us this barbarous dominion stinks. Let, therefore, your illustrious house take up this charge with that courage and hope with which all just enterprises are undertaken, so that under its standard our native country may be ennobled, and under its auspices may be verified that saying of Petrarch: Virtu contro al Furore Prendera l’arme, e fia il combatter corto: Che l’antico valore Negli italici cuor non e ancor morto. Virtue against fury shall advance the fight, And it i’ th’ combat soon shall put to flight: For the old Roman valour is not dead, Nor in th’ Italians’ brests extinguished.

Machiavelli, Niccolo (2006-02-11). The Prince (p. 96). Public Domain Books. Kindle Edition.

Machiavelli had a peninsula united in a common dream of Italy, of Rome, united by religion (if divided sometimes by the Pope) but politically divided. He could take the dream for granted and urge his Prince to practical affairs.

England Listened, Italy Could Not

Malory succeeded while Machiavelli failed. Political unity it seems is harder to achieve, even for a man of strategical genius. It was easier to give a nation still fundamentally united, though in turmoil, a dream of what could be again. Malory was writing to a fundamentally united England (if not yet Britain) that also lacked a great prince. However, if she could endure until one came, then she would survive. In fact, she ended up needing only to endure until a middling man, Henry VII, seized power in a worn out Britain.

Britain had been conquered many times and was a mongrel people: Angles, Saxons, Danes, Jutes, Celts, and Romans. What was England, and eventually greater Britain to be? What was she enduring this leadership struggle to be? Malory reminded Britain that she had seen it all before now (in the chaos after Uther) and had found her way to Arthur. Not even that great leader could last forever, Arthur dies as the title reminds us, but the English endure.

Malory found the story, the deeper national unity that was already there. He need only to give it voice and strength to endure rough times.

Machiavelli had a myth many times more potent, after all, the dream of the glories of Rome still haunts Italy, but the political unity was a puzzle that would take centuries more to shape. Italy was many nations with warring nobles, where England was one nation with warring nobles.

There is a warning here for our Republic. Machiavelli states that once citizens of a Republic have a taste of liberty, they will be impossible to subdue forever. However, once a people fragment, the Italian experience shows that reviving political unity is very hard. Reunion demands more than a Henry VII, but a convergence of unlikely events and a very great man indeed.

At the moment, the United States of America has political unity, but it is fraying in our divisive times. We do not have warring lords, but we do have a war of values as symbolized by the Red States and the White worn (symbolically) by opponents of the President. Red and White are fighting over what is, for now, one nation, but we are growing tired. Our leaders seem unworthy of the moment. This would be a good time for some Malory to revive a national myth, a unifying story for us all.

If we endure as a people, then some leader, someone with the practical skill Machiavelli taught, will arise. If not, if we divide, God save us, not even the wiles of a Machiavelli will be able to put us together again.

———————-

This is taken from the introduction to a lecture at The Saint Constantine School.