in Michaelangelo’s Il Giudizio Universale

Why study the religious history of the mustache? Why not?

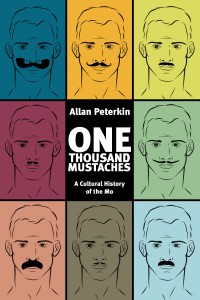

Allan Peterkin, M.D. wrote the book on the history of mustaches. Literally. As in, there’s only one contemporary published book on the history of mustaches. With whom could we better explore the topic of facial hair in world religions?

Peterkin is an Associate Professor of psychiatry and family medicine at the University of Toronto. In September, his One Thousand Mustaches: A Cultural History of the Mo was released by Arsenal Pulp Press. I asked him for a very stark example of the mustache’s role in a faith tradition.

Allan Peterkin: Within Christianity, in general, the mustache has been seen as the mark of the Beast, associated with the Devil. The mustache is very much linked to something evil, that persists.

Erik Campano: Is that limited to Christianity, or is it in all the Abrahamic traditions?

You don’t see the mustache alone, for example, for Jewish men. In Leviticus, there’s the instruction not to mar the corners of the face [Ed.’s note: Lv 19:27]. The mustache is never explicitly mentioned.

What does this mean, specifically, that you can’t mar the corners of your face?

It really means you’re not supposed to shave your beard. That’s the injunction.

It’s just a little strange, because beards aren’t necessarily square, so they don’t necessarily have corners —

Let’s give poetic license to the Bible.

All right. We have a lot of pictures of Jesus with a beard and mustache.

Yes, he wore the beard of his contemporaries — the beard of Jews, of rabbis. But then throughout history it’s back and forth as to whether the beard is godly or diabolical. It depends on which bishops decide to tax having the beard removed. There was a trial in the US — Amish men — and the beard being pulled out forceably by some disgruntled member of the community, and the perpetrator going to jail. [Ed.’s note: earlier this year the leader of a breakaway Amish sect in Ohio was sentenced to prison for consipracy in a hate crime, among other counts, after his followers forcibly cut the beards of other Amish men. The followers were also convicted.] In history, the removal of a man’s beard is symbolic of castration. Jewish men in the camps at times would have their beards pulled out altogether. You can imagine the torture of that. The removal of the religious beard is a very painful act, with an added dimension of humiliation, and possibly excommunication.

In your book, you also mention the Crusaders…

… who generally recognized that religious preaching to Saracens, or whoever had duties in the east and in the Holy Land, would be allowed to maintain their facial hair so as to blend into these communities. [Ed.’s note: Saracen was a late medieval European term for Muslim. This quote is actually from Peterkin’s 2001 work, One Thousand Beards.]

Yes, they obviously wanted to prosyletize and convert, and wearing a beard did make them seem less visibly dangerous or other, and that was part of the conversion experiment.

Franciscan monks often have beards and the simple habit. There’ s no injunction about shaving in certain religious orders. The Jesuits are typically clean-shaven. It’s not that there’s any rule, but just kind of a cultural style.

The Church of Jesus Christ

of Latter-day Saints

Mormon missionaries, as far as I know, are all clean-shaven.

Yes. I’ve never researched the question, but that would be my impression, too. [Ed.’s note: The press office of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has told me that indeed, all full-time male missionaries are required to shave each day, as a guideline set forth by the church.]

I’ve been interviewing mustached persons recently. One of them said that he has a number of born-again Christian friends, and that they react with more interest and enthusiasm to his mustache than other people. And the reason, he said, was that men who have become born-again Christians have often given up other things in their lives — for example alcohol, or sex outside of marriage. So, he said, they’re looking for new ways to be creative and experiment, and facial hair is one of them.

That’s an interesting observation. It wouldn’t necessarily be well-accepted in their communities if they grew a ‘stache, but you can see them wanting to push the envelope in a way that wasn’t too sinful, I suppose.

The Levy’s Unique New York! Tour Company

(click for bio)

Nowadays, in the West, in some communities, it seems to have become something of a more liberated phenomenon, like among middle-class to upper-middle class mostly Caucasian guys living in urban environments.

There’s the whole hipster tradition, desperately trying to be original, pushing then envelope. Keep in mind that many workplaces haven’t tolerated facial hair. So for a man to be able to get away with it at work probably means he has some stature, or freedom to express himself. And that would be true of artists, professors, people in the dot-com industry — but other professions, not so much. The two professions in which you don’t dare have a mustache or facial hair, including the beard, are banking and politics. The last American president to have facial hair was Taft, and he had a big ‘stache. Because your clients, voters, public, will misread your facial hair as something nefarious. So bankers and politicians aren’t willing to have their face misread. So they don’t take the chance. They’re clean-shaven — a tabula rasa.

Is it because the mustache covers up certain emotional expressions?

That’s been said to be the case, that part of our survival has been a very delicate sensitivity to reading subtle facial expressions — quivering lips, pursing lips, etc. So one of the ideas I came across for a bit of my research was that men with facial hair have something to hide — that they’re concealing something. the subtle, muscular expressions that convey what they’re really thinking, even if they’re saying the opposite. That’s been one of the objections. [Ed.’s note: in my interviews with mustached persons, I have also observed the opposite to be true sometimes; the mustache will enhance certain mouth movements. However, this could just be the way I, personally, process their facial expressions.]

The other association, from an evolutionary point of view, is, if you look at apes, when they’re starting to fight, they get something called jaw jut, where they stick their jaws out. And as we know, a large jaw is a symbol of the flow of testosterone. In most human cultures, we value a square, large jaw as being something very masculine, but it also has an aggressive connotation — apes stick out their jaw to make it seem bigger and more ferocious. So that may be part of the reading, too — that facial hair can be unpredictable.

But wouldn’t a mustache make your jaw look smaller because it makes the area above your jaw look larger?

It really depends on facial features. One of the reasons men wear the mustache is that they may be balding up top, or have a big nose, or thin lip. Men use facial hair for cosmetic, aesthetic reasons, to play up strong features and play down weak ones. So that certainly goes into the decision to wear a mustache at any given time.

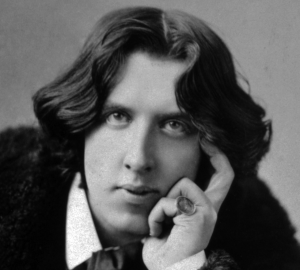

In general, this wave of facial hair that struck in the 90s has really seen every form of expression, including some new ones, but mostly ones that have been done before. Men are freer to express themselves with their faces than they have been any other time in history. But we may see a spring back to clean-shavenness. Oscar Wilde shaved when all his Victorian colleagues had beards. I predict that in he next five years, maybe the radical thing will be clean-shavenness, the next act of individualism and rebellion. We’re seeing a bit of it with Mad Men [Ed.’s note: a U.S. television period drama set in the 60s], and a throwback to the 50s. Keep in mind that the fashion industry is very invested in making men buy and do new things. So there will be those pressures to perhaps become clean-shaven again. I know for a fact that the multi-million dollar grooming industry wants men to buy razors, either electric or blade. So that all figures into the mix.

And the other thing is that men used to take cues from our clergy, our royalty, our politicians, and now we take cues from musicians, pop stars, TV and movie stars, and athletes. So if somebody famous goes very clean-shaven, or has some unusual facial hair, then obviously a lot of men are going to copy that. So it tends to be more a cultural phenomenon know, than a religious one, as it once was.

We know that Amish men often don’t have a mustache. They have the chin beard, and that often signifies marriage status, but it also probably has something to do with devilish associations with the mustache, and also militaristic associations.

The Amish being pacifists.

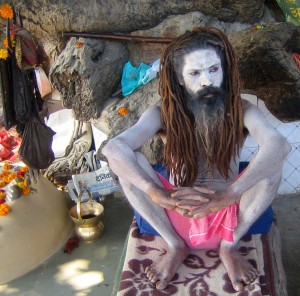

Yes and then, within Islam, you do see beards very commonly. Mustaches are more of a cultural signifier than a religious one. So Indian and Pakistani men often have mustaches. They’re not really interpreted religiously. They do indicate masculinity. If you’re a policeman in India, for example, you’ll be paid more if you have a mustache, because, apparently, you’re seen as more ferocious or virile.

[photo: Naresh Dhiman]

As a popular facial hair expression, yes.

Hinduism itself doesn’t really seem to have any strict instructions about mustaches.

Not to my knowledge.

Although you do mention in your book that Hindu gods have often been clean-shaven.

It’s true. That’s a retrospective reading of artifacts we see. Being clean-shaven is a class indicator over history as well; only rich men could afford the implements: the soaps, the water, the barber, the slave to do the shaving. So I imagine it was quite natural for any creation of the images of a god to have that link towards clean-shavenness. Being clean-shaven is being next to godliness.

Do we have any other religious texts, besides the Old Testament, that talk about mustaches?

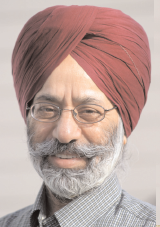

Sikhs are meant to grow the beard. [Ed.’s note: The Sikh practice of Kesh — not trimming one’s hair — was first laid down at the 1699 Khalsa. It is mentioned in some early Sikh texts, such as Siri Gur Katha, as well as the Reht Maryada, a code of conduct written by a committee of notable Sikhs in the 1920s and 30s.] It’s one of the obligatory physical representations of being a Sikh man.

In your book, you mention that the young Buddha has often been portrayed with a mustache.

That was a trend that was observed, but I’ve never seen any interpretation of why the Buddha was portrayed in that way. [Ed.’s note: Earlier representations of the Buddha, such as the Kanishka coins in the 2nd century C.E., frequently had mustaches. At least one source attributes this to Roman and Greek influence.]

Source: CoinIndia

I called Disney to find out if Yoda has a mustache. Because if you look at him, it’s really hard to tell. There’s no hair there, but above his lip it’s sort of shaped —

Yeah, he seems to have some kind of scraggle there.

And Yoda’s a Buddhist, right? [Ed.’s note: To be precise, many commentators have suggested that Yoda of Star Wars is a Zen master. There are also claims that Yoda’s face was modeled on that of Buddhist teacher Tsenzhab Serkong Rinpoche — who (at least for part of his life) did not wear a mustache. I am still waiting for a confirmation from Corporate Communications at The Walt Disney Company on the details of Yoda’s face. Feel free to pose them the question yourself.]

Walt Disney wore a mustache, but for decades, any man working for Disney theme parks was not allowed to have a mustache or beard. That changed in the last few years, but it was verboten, and probably parents wanted to take their kids to an environment where everybody was clean-shaven.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but there’s a contrast here. The beard is a symbol of manliness, and hence maturity or spiritual maturity, but the mustache is unwanted — it’s a symbol of the nefarious.

The mustache has always been the emblem of the other, in the Western world in particular. In the book, I talk about the three “f’s”: the fop, the foreigner, and fiend. The fop is the effete man who is overly concerned with his appearance. That in itself would suggest not a very godly attribute. The foreigner is the other. So if you’re a WASP, you might refer to someone of Mediterranean extraction with a mustache as being a foreign other. And then the fiend: typically through Hollywood and most representations in books and film, the short-handed symbol that the guy’s a villain is that he’s twirling his mustache, that he’s got evil on his mind. Then in the 1970s the mustache takes on a very sexualized aspect. That’s because of gay men in the Castro in San Francisco wearing the ‘stache, porn actors often having mustaches, and swingers too. So it became very sexualized in a way that’s ambiguous, so that many men got scared off by the mustache because they didn’t want their sexuality to be misread.

Was there actally some kind of religious reaction to the 70s ‘stache?

To the gay mustache, for sure. It certainly was an emblem of being gay — the clone look, it was called — very militaristic, hyper-masculine. Back in the 60s, the hippies would wear long hair, straggly beards, and sometimes the mustache with long hair, and probably pushing the envelope, saying that this is a taboo style, but I’m free to do what I want, and it’s also highly sexualized. On the other hand, it was very popular particularly in the British military. You could tell an officer’s rank by how bushy his mustache was allowed to be.

When I asked mustached men about how their mustache relates to their sprituality, I actually got a common answer. It was that the growth of their mustache reflected the development of themselves as men, and in some cases they said it reflected their spiritual development. So has the mustache become a symbol of maturity of some kind?

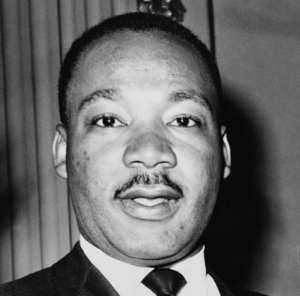

For young men, it may be a fad or a trend. For older men — fathers, grandfathers, someone who wore the mustache forever — it became like an extra limb. African-American men, for example, have traditionally worn the mustache. It wasn’t a fad. It persisted. I think nowadays, though, we can say that the 21st century is the freest time in history for men to experiment with their faces and facial hair. Generally, after both world wars, you had to be clean-shaven to succeed, sort of the Mad Men ethos, as such.

But now men can do whatever they want — since the 90s, with the return of the goatee. Everything else was unleashed after that: soul patches, sideburns, combination looks, stubble. The mustache was the final frontier, and so it doesn’t surprise me that men wanting to have an impact, to have their own trademark, have embraced the mustache. So I think there’s something about a kind of playful rebellion in there. There’s something about a performance of masculinity, that guys are saying, this is virile, but I’m not taking myself too seriously.

But now men can do whatever they want — since the 90s, with the return of the goatee. Everything else was unleashed after that: soul patches, sideburns, combination looks, stubble. The mustache was the final frontier, and so it doesn’t surprise me that men wanting to have an impact, to have their own trademark, have embraced the mustache. So I think there’s something about a kind of playful rebellion in there. There’s something about a performance of masculinity, that guys are saying, this is virile, but I’m not taking myself too seriously.

In my experience, mustached men tend to be fairly outgoing because they will invariably still be asked, why do you have a mustache? You’re a young guy — why do you wear a mo? It’s sort of like pregnant women, right? Everybody feels free to talk about the belly. :-{