The session after lunch began with Brandon Hawk talking about the use of apocryphal narratives in medieval English preaching (as also in art), using the interdisciplinary approach of transmission studies. His specific focus was Pseudo-Matthew, which was particularly popular in that context, and which is used in the manuscript known as Bercelli 6, a Christmas sermon which illustrates the focus on Jesus' deeds in preaching in Anglo-Saxon England. He engages the study of art as evidence for narrative traditions and their uses. Hawk read a bit of the Old English sermon, since someone asked him to. Some of the images he has examined, such as Jesus with a palm tree, suggests that the artist had Pseudo-Matthew in mind. The story and the artistic rendering both have Christ making a palm tree bend itself to feed Mary when they had no other food. In the discussion afterwards, Anne Moore asked whether the halo indicates that it is Anna who is depicted rather than a midwife. Also, Joseph is depicted in this particular work of art as looking at Jesus and pointing at his own eyes, indicating his seeing and believing, which contrasts with other art in which he is looking away and sometimes even depictd as tempted by Satan.

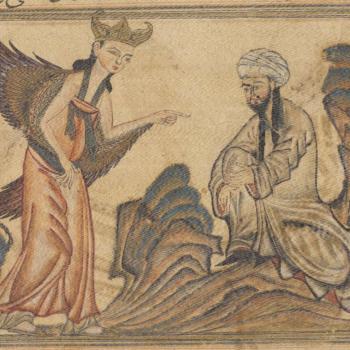

The second paper in this session was by Tim Pettipiece, on Manichaean redaction of the Secret Book of John. He began by noting the lack of attention to the Manichaeans, and the need to look at that tradition's reception of works other than the Gospel of Thomas. Pettipiece suggested that earlier versions of Nag Hammadi works influenced Mani, and that in turn some of the Nag Hammadi (Codex 2) texts show indications of Manichaean and anti-Manichaean redaction. There are noticeable editorial seams in the long version of the Apocryphon of John. It also has Manichaean themes (light and darkness and the mixture thereof) and terminology. The spelling Yaltabaoth is an interesting variation of the usual spelling of this name of the demiurge, listed here together with the other names Saklas and Sammael. Too ofter scholars fail to consider the differences between the long and short versions, and likewise translations are prone to run them together. The epilogue also shows signs of Manichaean influence. Pettipiece sees the influence as occurring at the stage of transmission in Coptic. They may have been involved in scribal culture in Lycopolis (cf. Guy Stroumsa). We often pay attention to debates between texts, but not within texts. Pettipiece explicitly raised questions about intentionality – what might have motivated these redactions, and how were these texts used? This example relates in interesting ways to the questions raised in the previous session about forgery. What is the category for redaction of a work that was already pseudepigraphal from its composition? Tony Burke asked in the question time about the possibility that Codex 2 might deserve to be considered a Manichaean codex, and if so how others of the codices which relate physically to that codex might be considered Manichaean as well. It remains to be investigated whether the Manichaean influence is from the last scribe or an earlier one. Jamet Spittler asked if he had a narrative for how this came about. Pettipiece said he is looking forward to the forthcoming book on the monastic context of the Nag Hammadi texts. One of the SBL Christian Apocrypha sessions in November will look at this topic. The last question was about how Manichaeans might have used the Apocryphon of John, since it is not listed among their scriptures. Pettipiece suggests that someone was trying to sneak Manichaean “color” into a Sethian text, and not using it liturgically.