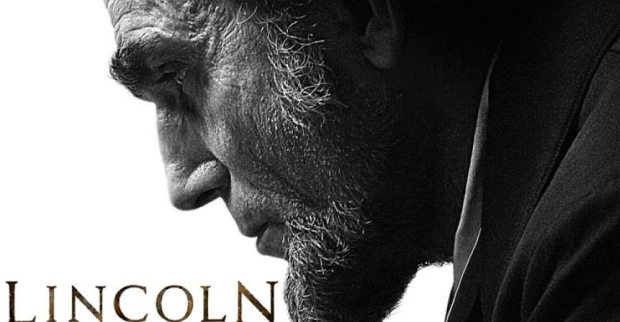

Over the next three days, I’ll be blogging about a few of the Best Picture nominees leading up to this Sunday’s Academy Awards. Here’s the first of the series, on Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln.

I like writing positive reviews. They are much more challenging and rewarding than simply pointing out a film’s flaws. But I don’t think I can do that with the Best Picture nominees this year, save for one (which I’ll cover last in this series of posts). The rest of the Best Picture nominees suffered from a common problem: they fail to capture moral and historical tension and make no real challenge to the viewer.

Stories need challenges and they need uncertainty in face of those challenges, not only to keep the viewer engaged, but also to be true to the struggles of human life. Stories where the ending is already common knowledge (a surprising percentage of this year’s nominees) need, therefore, to find a creative way to engage the viewer.

Lincoln is no archetype for such creativity. Instead, it’s a classic example of how Hollywood can take a complex and challenging historical moment and whitewash it with hagiography and sentimentality. The movie tells the inspiring story of the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, focusing on the inspiring people who accomplished it, as they do inspiring things to inspire people to be inspiring. A movie about the Civil War offers tons of opportunities to explore complex moral questions. Unfortunately Lincoln does nothing to question our moral certainty, and it does nothing to suggest that these real, historical people were struggling with these questions.

The very first scene, a cheesy recitation of Lincoln’s now famous Gettysburg address, alerts us that the film is going to be sentimental and anachronistic, and that it does not truly respect its audience. Somehow, I doubt that too many soldiers recited the Gettysburg Address back to President Lincoln in glowing tones, as the characters in the movie do.

And the movie just gets worse from there, passing up countless chances to engage with real questions. For example, at one point, concerned citizens tell President Lincoln that they support the Amendment because they support him, but they would also just as well not have freed slaves taking their jobs away. There is an opportunity here to force viewers to consider: is this what I would think? Is this what I think today, regarding immigration, or minimum wage laws? If so, is this a problem? If not, why not? The movie could have explored these themes. It chose not to. Nary a concerned citizen is heard from again.

The film could also have shown characters struggling over the morality of the means they’re using to abolish slavery: how far would you go to pass the Thirteenth Amendment? Would you bribe? Would you buy? Would you lie? Would you continue a war killing thousands? President Lincoln himself is shown to be stalling a potential resolution to the war in order to pass the Amendment—a war that is killing hundreds of Americans each day that it continues. Yet none of these allusions means much. The film is already completely certain that passing the Thirteenth Amendment is worth any cost. Lincoln is certain. Stevens is certain. The audience knows that, of course, the Thirteenth Amendment was passed, meaning the many sacrifices were not made in vein. It is difficult, then, to feel the painful uncertainty of the sacrifices the characters do choose to make.

That the Abraham Lincoln of this movie seems to already know the ending of anti-slavery struggle is embarrassing because the Lincoln of history was not as single-minded as the film suggests. The man who passed the Thirteenth Amendment is also the man who said that if keeping every slave in chains would save the Union, he would do it. Clearly something changed. What? How? The movie gives us no idea—it is too busy taking slow zooms onto various saintly characters.

Of course, we, in retrospect, see very clearly the morality at stake here. We are quite certain that slavery had to be abolished. But it could not have been so clear to the characters then. The real, historical Lincoln would, in his second inaugural address, proclaim that if endless war were required to expiate the guilt of slavery, then endless war there will be. Suffering is the antidote to sin; guilt drives us to purify ourselves; sacrifice is the only sure way to transform oneself.

This is a moving message because it is a difficult message. When it is trivialized, it loses its force. By doing nothing to make this movie difficult, the movie loses its message. The story fundamentally boils down to: Lincoln is a great guy. Stevens is a great guy. They want to do this great thing. They do this great thing.

It might be too much to ask of Spielberg to avoid sentimentality altogether, but there are many ways a director can create a rousing moment without slipping into the sloppiness we see in Lincoln. In Schindler’s List, for instance, one of the more sentimental moments is Oskar Schindler’s climactic emotional breakdown, where he cannot believe that he did not do more, that he only managed to save these thousand Jews. Yet in that case, the movie had done little but show us the horror of the Holocaust for three hours. Sentiment meant something because the world was a real world with real horrors.

The world of Lincoln is not a real world. The sets are fantastic, the costuming is superb, and the soft pallet evokes the 1860s with aplomb. But this is not the 1860s. This is a wrung-out, stripped down version that has ejected all true conflict, all true moral difficulty, and left us with a film that is not sure what it is about. President Lincoln deserved better.