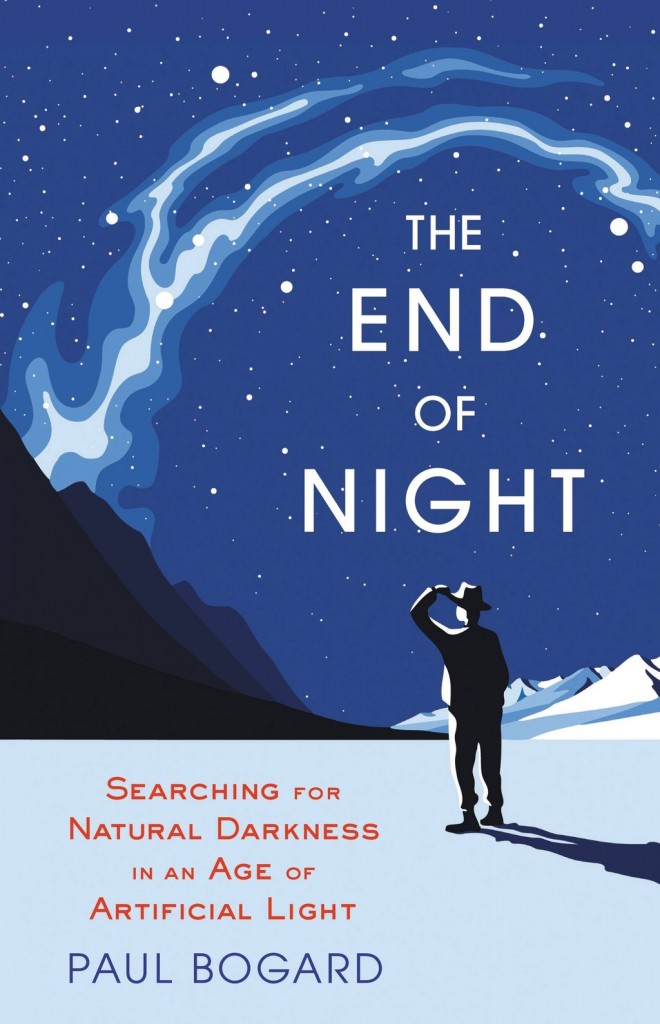

Paul Bogard’s The End of Night has as much to say about the night sky as it does about the people who live under it. In his search for the last of our nation’s natural darkness, Bogard makes room for everyone from the president of the unlikely Las Vegas Astronomical Society to a woman who, visiting a dark rural area for the first time, exclaimed, “What are all those white dots in the sky?”

The sorry truth is that most of us are scarcely more aware of the night. Light pollution, the phenomenon of excess artificial light swamping the night sky, has only recently came to our attention; it wasn’t until 2001 that an amateur astronomer named John Bortle created a 9 to 1 scale to measure the darkness of skies. In a 9 such as New York City, 98 percent of the stars we should be able to see have been wiped out by light pollution. Most Americans currently live under skies ranging from 9 to 7—“inner-city” to “sub- urban”—and eight out of ten children born today will never see the Milky Way (which requires a “rural” sky of 4 or 3).

In this book, Bogard sets about traveling from 9s in search of 1s, taking his methodology from a Wendell Berry line: “To know the dark, go dark.” He writes, “Along the way, I would chronicle how night has changed, what that means, what we might do about it, and whether we should do anything at all. I wanted to understand especially how artificial light can be both undeniably wonderful, beautiful even, and still pose a long list of costs and concerns.” Refreshingly, the book is hardly a polemic against electric light, as evidenced in Bogard’s balanced and engrossing account of streets before street lighting: “To go out at night was to risk one’s life, whether by a criminal’s hand or a misplaced step.” Rather, Bogard argues that we’ve taken a good thing too far.

Most streetlights, for example, are far brighter than they ought to be; drivers’ eyes don’t have sufficient time to adjust between the alternating super bright and dark patches along the road. Bogard explains, “In dimly lit situations, our pupil expands, our iris relaxes, and thirty times more light can enter our eye.” Glare reduces contrast, which hampers the human eye’s ability to see (consider how old prison uniforms featured black and white stripes to maximize contrast). Alan Lewis, optometrist and former president of the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America, vouches that about 80 percent of streetlights are badly designed, making them contrast-reducing glare sources. In other words, we would be able to see just as well, if not better, in lower light levels “that would allow the stars back into our skies and make our streets safer by eliminating glare.”

Perhaps Bogard’s most challenging claim is that bright lights do little to deter crime. He cites numerous studies, including a 2000 study conducted by the city of Chicago, which have found little or no statistically significant evidence that street lighting decreases crime. Bogard adds, “The joke I heard in London is that criminals actually prefer to work in well-lighted areas because they, too, feel safer. Studies bear this out: Light allows criminals to choose their victims, locate escape routes, and see their surroundings.” Bogard’s evidence is interesting, but he misses the opportunity to strengthen his argument by engaging more with his opponents—for example, the recent case of Oakland, California attributing a spike in crime to the dimming of streetlights in 2011.

All told, the current state of our street lighting may have less to do with our safety than with energy companies’ preference for not letting their generators stand idle at night. In a similar vein, Bogard notes that gas stations, shopping malls, and other retail establishments are not lit primarily for safety, but to attract business. Over the years, lighting has grown brighter across the board, with no single building wishing to appear dimmer and less inviting by contrast. In the words of Roger Narboni, a lighting designer in Paris, we are addicts of electric light, oblivious to the waste and ugliness we create.

But Bogard goes further than these pragmatic considerations, insightfully noting that the association of light with safety is as deeply entrenched as the fear of the dark. His book, therefore, is twofold in its methodology. On the one hand, he gives a pragmatic and journalistic account of the fate of our night skies. On the other hand, he takes us on a sensory journey from a view of dazzling constellations in Morocco to the best streets to see London’s 1,600 remaining gas lights to Austin, Texas’ famed column of bats to the surreal hours of the night shift in an emergency room. His prose steeps us in the facts and the feeling of the night many of us don’t even realize we’ve lost, and seeks to inspire us with its beauty—“I’m talking about a night sky that leaves you breathless, that makes you want to study the stars, or write poetry, or dance.”

On a deeper level, then, Bogard wants to make a case for beauty itself. In a moment of discouragement, an astronomer and fellow dark-sky advocate Bogard talks to quotes a striking passage by art historian John Van Dyke:

To speak about sparing anything because it is beautiful is to waste one’s breath and incur ridicule in the bargain. The aesthetic sense—the power to enjoy through the eye, the ear, and the imagination—is just as important a factor in the scheme of human happiness as the corporeal sense of eating and drinking; but there has never been a time when the would admit it. The “practical men,” who seem forever on the throne, know very well that beauty is only meant for lovers and young persons—stuff to suckle fools withal. The main affair of life is to get the dollar, and if there is money in cutting the throat of Beauty, why, by all means, cut her throat.

Beauty—what is it good for? Such is the utilitarian perspective that a Christian understanding of beauty could correct. Flannery O’Connor, by way of Aquinas, argued that art is a thing good in and of itself. We therefore ought to love beauty for its own sake—as God did in calling creation “good”—rather than trying to make use of it to serve our own ends.

Bogard’s findings make it clear that Americans, Christians included, are terribly out of touch with nature and the importance of natural darkness for our bodies. On the topic of misconceptions about light pollution, one campaigner paraphrases the “apathy and ignorance” of the man on the street as, “Light, good; dark, bad. Says so in the Bible.” Bogard claims that Western thinking behind lighting, with the implied influence of Christianity, has always strived “to take the dark out of night.” Yet he also notes that darkness in the Judeo-Christian tradition is much more complex and mysterious upon close inspection—Jacob wrestling with the angel and Jesus praying in Gethsemane are just two examples of people who became closest to God in times of trial in the nighttime. Perhaps the night particularly brings out our capacity for subtle attention, quietness, and perseverance—good guidelines for how we ought to relate to one another, and which we risk symbolically losing along with our natural night.

In inviting readers along to experience and fall in love with the night sky, Bogard is betting that beauty—the knowledge, appreciation, and love of it—will gradually prompt us to reclaim the darkness of night as it was meant to be. His book is a reminder that we need to take the environment and beauty entrusted to us seriously, with reverence and love. Otherwise, we will only come out in a deservedly bad light.