General Lew Wallace had lived a colorful life of his own before his novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was published in 1880. By then, he had defended Washington, D.C. from Confederates during the Civil War, served on the court-martial that tried Lincoln’s assassins, and, as Governor of New Mexico Territory, dealt with outlaws like Billy the Kid.

General Lew Wallace had lived a colorful life of his own before his novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was published in 1880. By then, he had defended Washington, D.C. from Confederates during the Civil War, served on the court-martial that tried Lincoln’s assassins, and, as Governor of New Mexico Territory, dealt with outlaws like Billy the Kid.

But what he really wanted to do was write — and so he wrote his novel about a Jewish prince who is betrayed by a Roman tribune during the time when Jesus lived. Ben-Hur was spurred by Wallace’s love of stories like The Count of Monte Cristo, but it was also motivated by an encounter with Robert Ingersoll, a famous agnostic who was passionately opposed to Christianity. Until that meeting, Wallace had been indifferent towards religion, but afterwards, he felt he needed to research Christianity for himself — and thus he became a believer.

Wallace died exactly one century ago, but he lived long enough to see his story (which was as famous for its sea battle and chariot race as it was for its religious content) become a popular stage production in 1899. For the chariot-race sequence, real live horses ran on treadmills pointed at the audience.

Films were just getting started around that time. In 1907, two years after Wallace’s death, the Kalem company produced the first film to bear his novel’s name; it lasted only 15 minutes, and was little more than a glorified race sequence. But it was made without the permission of Wallace’s estate, which sued for copyright infringement in a precedent-setting case.

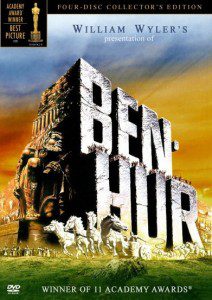

Two more films followed — one produced in 1925, near the end of the silent era, plus the famous Charlton Heston-starring remake produced in 1959. The Bible-epic genre was at the peak of its popularity, and the film won an unprecedented 11 Academy Awards (a feat matched only by 1997’s Titanic and 2003’s The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King).

Both films are now available in a four-disc DVD set, which also comes with several hours of bonus features, including two documentaries on the film and its legacy, an audio commentary, and various newsreels, screen tests and other bits of archival footage.

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925)

directed by Fred Niblo

In some ways, the silent version is the more Christian film, but it is also the more risqué. The film clocks in at 2 hours and 23 minutes, and devotes the first 15 minutes alone to the Nativity; later scenes incorporate the teachings of Christ, including the Sermon on the Mount and his defense of the woman caught in adultery, as well as Palm Sunday, the Last Supper, and the Crucifixion. Jesus himself is never glimpsed directly; all we see is his hand, gesturing from the edge of the frame. And while the film was mostly shot in black-and-white, many of these scenes are shot in two-strip Technicolor, to underscore their sacred nature.

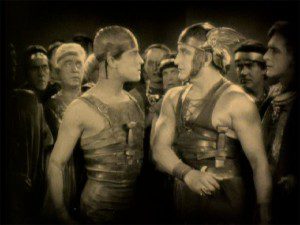

But Technicolor is also used for one of the not-so-sacred sequences. Judah Ben-Hur (played by Ramon Novarro), the Jewish prince who was unjustly accused of trying to kill a Roman governor, and who was then sentenced to row the oars as a galley slave for the rest of his life, sees his fortunes reverse again when he saves a Roman consul (Frank Currier) during a sea battle, and is then adopted by that consul. The scenes in Rome that follow are partly shot in Technicolor — and they start with a victory parade led by topless women scattering flowers!

Thus this film toes the line between piety and exhibitionism that was common to other Bible epics produced during the 1920s. There are one or two other moments of partial nudity in this film, but nothing serious. More significant is the way the film brings its two parallel storylines together — the one about Christ, and the one about Judah Ben-Hur — by portraying Judah as a man who eagerly awaits the Messiah, and who is prepared to use his wealth and social status to raise entire legions to help the Messiah fight against the Romans.

Judah’s expectations are thwarted, of course, when Jesus willingly goes to the cross. And the film’s other characters, including Judah’s mother and sister, as well as the Egyptian magus Balthazar, talk of the need to have faith in Christ, and to pray. The film ends with Judah declaring faithfully, “He is not dead. He will live forever in the hearts of men.”

Directed by Fred Niblo (whose other films include the Douglas Fairbanks classic The Mark of Zorro) and a handful of other, uncredited directors, this version of Ben-Hur stands up very well next to its remake. The film has some artful visuals, such as the silhouettes that skulk across the foreground when Judah looks for his mother and sister in the Valley of Lepers. The treacherous Roman tribune Messala (Francis X. Bushman) is a bit of a one-dimensional bad guy, but within the conventions of the silent era, this take on the character doesn’t seem so odd.

The set pieces are also fantastic, even by today’s standards. The 1925 film’s chariot race holds its own against the one in the remake, but its sea battle is arguably even better than the one that came later, partly because it seems to rely less on miniatures and more on the life-size galleys that were easier to build back when Hollywood worked with non-union crews. And the earthquake that marks the death of Christ leads to a disaster-movie moment that would be eclipsed just a couple years later by the storm in Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings.

Ben-Hur (1959)

Ben-Hur (1959)

directed by William Wyler

The 1959 version — which clocks in at over 3-and-a-half hours, not including the overture and entr’acte music that plays at the beginning of each disc — is better remembered, and very popular with Christian audiences. But this version actually takes a step back from the overtly Christian tone of the earlier film, in favor of a message that is more subtly humanistic.

Directed by William Wyler, who won Oscars for Mrs. Miniver and The Best Years of Our Lives before Ben-Hur earned him a third statuette, the film still features some religious concepts and images. It begins with a Nativity sequence, now only about five minutes long, and climaxes with the Crucifixion; but there are very few episodes from Jesus’ life between those points. And just as we never see Jesus’ face, we also never hear his voice; so the teachings of Christ, which appeared on title cards in 1925, are now transmitted by other characters, who sometimes phrase them in ways that underscore the film’s more secular inclinations.

Produced after the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, the film was motivated partly by a desire to bring the world’s major religions together. Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) proudly identifies himself as a Jew, but never professes belief in a Messiah of any sort; his opposition to Rome is fuelled more by personal feelings of vengeance than by any sense that he could help to fulfill prophecy, so he never quite becomes a Christian.

Early on, a Roman officer sums up Jesus’ message by saying that “God is near, in every man.” Esther (Haya Harareet), the freed slave girl who falls in love with Judah, tells him that Jesus preaches about love and forgiveness, and Judah’s last words in the film — “I felt his voice take the sword out of my hand” — are less a profession of faith than a profession of pacifism. In his commentary, film historian T. Gene Hatcher also notes that Judah’s mother and sister are healed of leprosy more because they pitied Christ than because they followed him.

Judah also befriends a scene-stealing Arab sheik (Hugh Griffith) who supplies the horses that pull Judah’s chariot; and before the race, the sheik gives him a Star of David to wear, and says it will shine that day for Jews and Arabs alike. When Wyler accepted Griffith’s Oscar for this role, he praised the actor for his portrayal of a humorous and sympathetic Arab chieftain, and lamented that the film had been banned in some Arab countries.

The film still has many strengths. Produced just three years after Cecil B. DeMille’s remake of The Ten Commandments, which also starred Heston, Ben-Hur is a much more intimate film, and makes greater use of shadows than DeMille’s film, which tended more towards stagey theatrics and bright displays of color. The sea battle and chariot races are technical marvels, both for their depiction of savage violence and, in the race’s case, for its masterful use of sound effects. Wyler gets full-blooded performances from all of his actors, and Miklos Rozsa’s music — by turns romantic, exciting, and occasionally transcendent — is also superb.

The DVD’s bonus features are a mixed bag. One documentary highlights Wallace’s faith but also gives ample time to Gore Vidal, who worked on the film’s script very reluctantly, and who repeats his assertion, disputed by Wyler and Heston, that Boyd was instructed to play Messala as though he had a homosexual attraction to Judah. Another documentary looks at the influence of Ben-Hur on more recent epics, such as Gladiator and, uh, Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace. (No less than three clips are shown from this latter film.) Most alarming of all, perhaps, is some screen-test footage that features Leslie Nielsen as Messala!

Wyler happened to be an assistant director on the 1925 film, and according to Heston, Wyler used to look around the set of the 1959 film and wonder which of his own assistants would make the next version. That hasn’t happened yet, but thanks to this new DVD set, audiences can experience and appreciate both of the epics based on Wallace’s novel anew.

— A version of this review first appeared on the Christianity Today website.